- How HPV Leads to Cancer

- Cervical Cancer and HPV

- Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancers Linked to HPV

- Genital and Anal Cancers Associated with HPV

- Why Not Everyone with HPV Gets Cancer

- Role of Immunity, Genetics, and Co-Infections

- Ayurvedic View: Ojas Depletion, Agni Imbalance, Vyadhi Sankara

- Prevention and Risk Reduction

- Ayurvedic and Integrative Cure Approach

- Explore the Complete Ayurvedic Cure

- Hidden Truths and Critique

- FAQs

- References

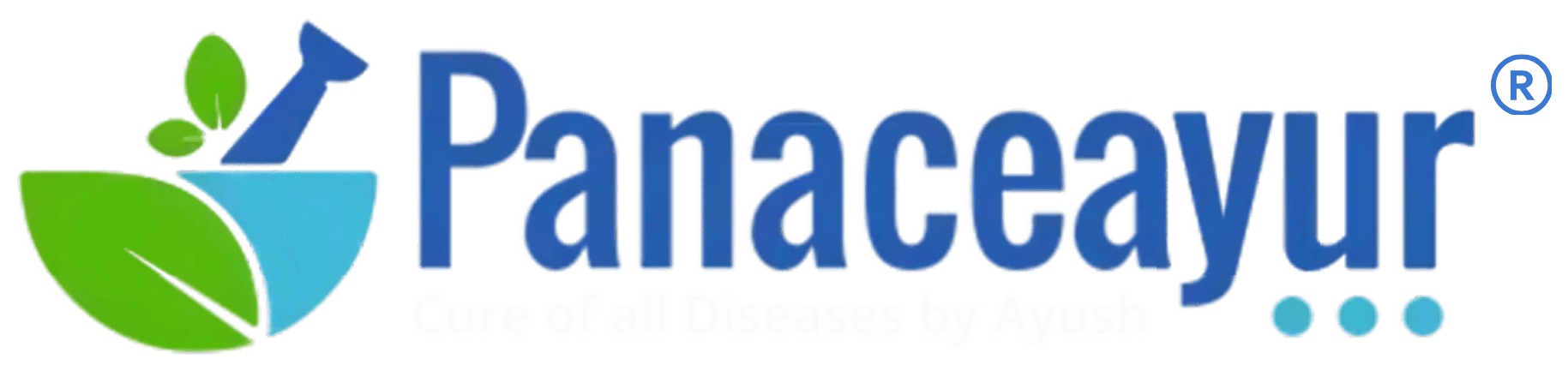

HPV and Cancer Risk-it is the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide, with an estimated 80% of sexually active individuals contracting it at some point in their lives [1]. Although the majority of infections resolve spontaneously, persistent infection with high-risk strains can lead to the development of cancers in multiple sites, including the cervix, oropharynx (throat, tonsils, and tongue), anus, penis, vulva, and vagina [2]. The risk arises not from the initial infection itself, but from the virus’s ability to persist and trigger cellular and genetic changes over time [3].

Modern research shows that oncogenic HPV types such as HPV-16 and HPV-18 are responsible for nearly 70% of cervical cancer cases globally [4]. These viral strains disrupt two key tumor-suppressor pathways—p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb)—which normally regulate abnormal cell growth. When these safeguards are bypassed, infected cells gain the ability to proliferate unchecked, a phenomenon termed viral oncogenesis [5]. This makes HPV one of the leading infectious agents associated with cancer worldwide [6].

Ayurveda provides a complementary lens to understand HPV and its long-term risks. Conditions described in classical texts—such as Yoni Vyapad (gynecological disorders), Mukha Roga (oral diseases), and Upadansha (sexually transmitted lesions)—parallel many of the clinical manifestations of HPV [7]. Ancient scholars also recognized microscopic causative agents (Krimi) and highlighted the role of Rakta (blood) and Shukra Dhatu (reproductive tissue) vitiation in chronic disease progression [8]. This aligns closely with the modern understanding of HPV persistence and its deep-seated effects on host tissues.

The growing burden of HPV-related cancers highlights the need for prevention, early detection, and integrative treatment strategies [9]. While modern medicine emphasizes screening and vaccination, Ayurveda focuses on strengthening Ojas (vital immunity), balancing Agni (metabolic fire), and applying Rasayana therapies to prevent long-term viral dominance [10].

This article explores HPV’s role in cervical, oral, and genital cancers, while contrasting modern biomedical approaches with Ayurvedic root-cause healing strategies. The integration of these perspectives offers a holistic roadmap for prevention, management, and potential eradication.

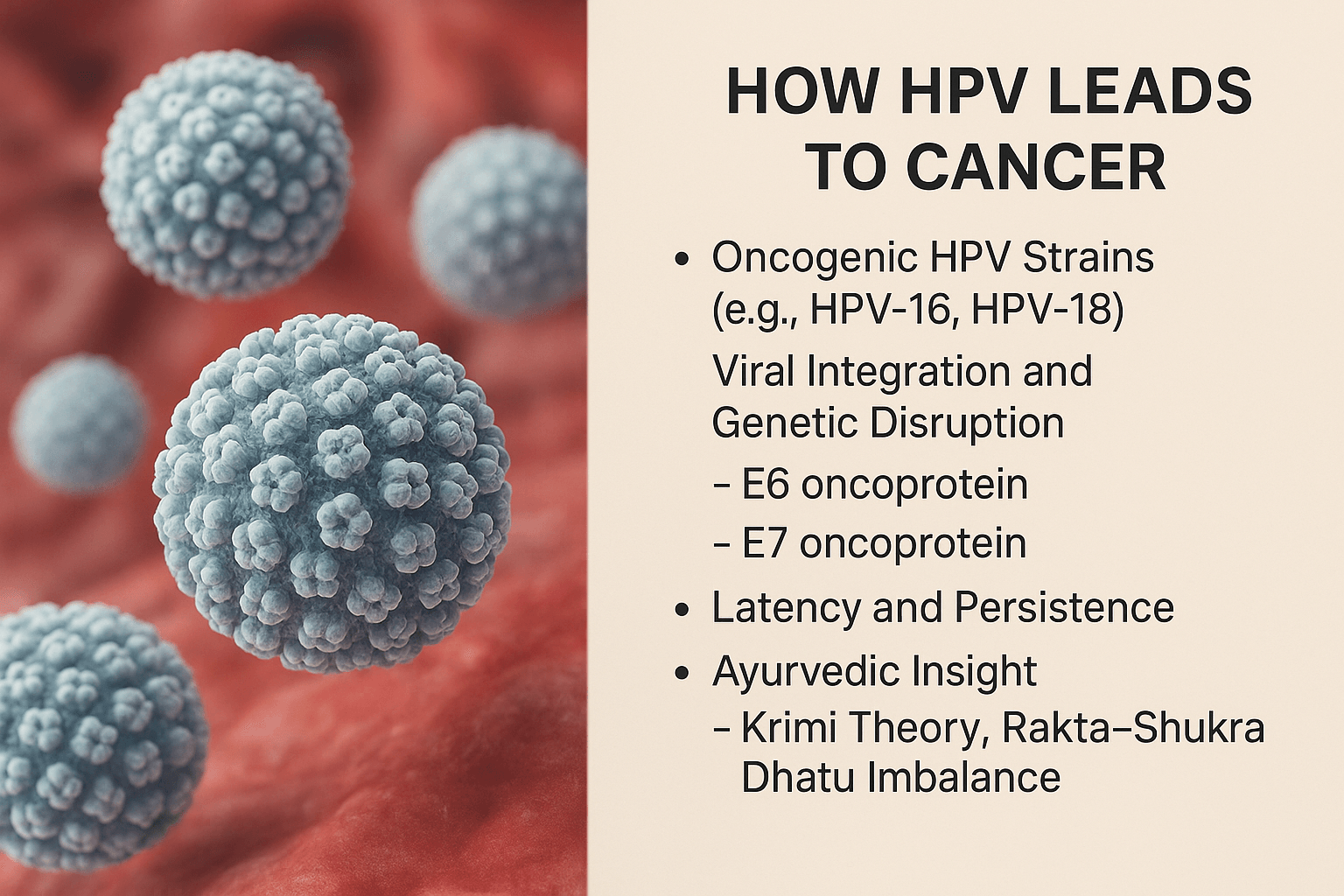

How HPV Leads to Cancer

Not all strains of human papillomavirus (HPV) are equally dangerous. Out of more than 200 identified HPV types, a subset is classified as oncogenic, or cancer-causing. Among these, HPV-16 and HPV-18 are the most significant, together accounting for the majority of HPV-related cancers worldwide [4].

Viral Integration and Genetic Disruption

The cancer-causing potential of HPV lies in its ability to integrate into the host cell’s genome. Unlike low-risk HPV strains, which remain as episomes and usually cause benign warts, high-risk strains insert their genetic material directly into the host DNA. This integration leads to continuous expression of two viral oncoproteins—E6 and E7 [5].

- E6 protein binds to and degrades the p53 tumor suppressor, a critical “guardian” of the genome that normally halts the cell cycle in the presence of DNA damage.

- E7 protein inactivates the retinoblastoma (Rb) protein, which controls unchecked cell division.

By neutralizing these safeguards, HPV creates an environment where abnormal cells escape apoptosis and begin to proliferate uncontrollably, setting the stage for precancerous lesions and, eventually, invasive cancer [6].

Latency and Persistence

Most HPV infections clear within 6–24 months through immune surveillance. However, when the virus persists—especially high-risk types—it establishes a long-term latent infection. Persistence is the single most important risk factor for progression from infection to cancer [3]. This silent latency explains why women can contract HPV in their 20s but not develop cervical cancer until their 40s or 50s. Similarly, oral and anal cancers linked to HPV often manifest decades after initial infection.

Ayurvedic Insight

Ayurveda, while not describing HPV in modern microbiological terms, offers striking parallels. The classical concept of Krimi (pathogenic organisms) reflects the recognition of invisible agents capable of disrupting systemic balance [7]. In this context, persistent HPV infection can be seen as a manifestation of Krimi lodged in vulnerable tissues.

Further, the progression toward malignancy aligns with Rakta–Shukra Dhatu Dushti—a state where the blood (Rakta) and reproductive tissue (Shukra) become vitiated due to chronic exposure to pathogens and weakened immunity [8]. This vitiation reduces Ojas (vital resilience), impairing the body’s ability to clear the infection naturally. The Ayurvedic emphasis on purifying Rakta and rejuvenating Dhatus provides a holistic framework for preventing the virus from taking a cancerous trajectory.

Cervical Cancer and HPV

Statistics and Global Burden

Cervical cancer remains one of the most common cancers among women worldwide, with more than 600,000 new cases and over 340,000 deaths reported annually [11]. The burden is disproportionately high in low- and middle-income countries, where access to screening and vaccination programs is limited [12]. Almost all cases of cervical cancer are linked to persistent infection with high-risk HPV strains, making it one of the clearest examples of a virus-driven malignancy [4].

Why Persistent HPV Is the Main Driver

Although most HPV infections resolve naturally, the persistence of high-risk types such as HPV-16 and HPV-18 is the strongest predictor of progression to cervical cancer [3]. Viral integration into host DNA leads to uncontrolled activity of the E6 and E7 oncoproteins, silencing the protective functions of p53 and Rb [5]. This process transforms healthy cervical epithelial cells into precancerous lesions, which, if undetected and untreated, may progress to invasive cancer over several years [6].

Symptoms and Early Warning Signs

Cervical cancer in its early stages is often asymptomatic. This is why many women may carry high-risk HPV infections for years without realizing it. When symptoms do appear, they may include:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding (between periods, after intercourse, or post-menopause).

- Unusual vaginal discharge that may be watery, pink, or foul-smelling.

- Pelvic pain or pain during intercourse.

Because these symptoms typically occur only in advanced stages, regular screening is critical for early detection [13].

Screening Methods

Two modern diagnostic methods are widely recommended:

- Pap smear (Pap test): Detects precancerous or abnormal cervical cells, allowing intervention before cancer develops.

- HPV DNA test: Identifies high-risk HPV types directly, even before cellular abnormalities are visible.

Combined screening has been shown to reduce cervical cancer mortality by up to 70% when implemented at a population level [14].

Ayurvedic Interpretation

Ayurveda describes cervical disorders under Yoni Vyapad—a category of gynecological diseases characterized by abnormal discharges, pain, and bleeding [7]. Persistent infection and its progression toward malignancy reflect chronic Rakta (blood) vitiation, leading to deeper tissue involvement. Furthermore, Ayurveda emphasizes Garbhini Charya (guidelines for reproductive and gynecological health), highlighting the importance of preventive care, purification, and strengthening of the reproductive system to avoid long-term complications [15].

From this perspective, persistent HPV infection can be seen as a form of deep-seated Krimi disorder aggravated by weakened immunity and imbalanced Shukra Dhatu. Ayurvedic management focuses not only on treating symptoms but also on restoring systemic harmony to prevent malignant transformation.

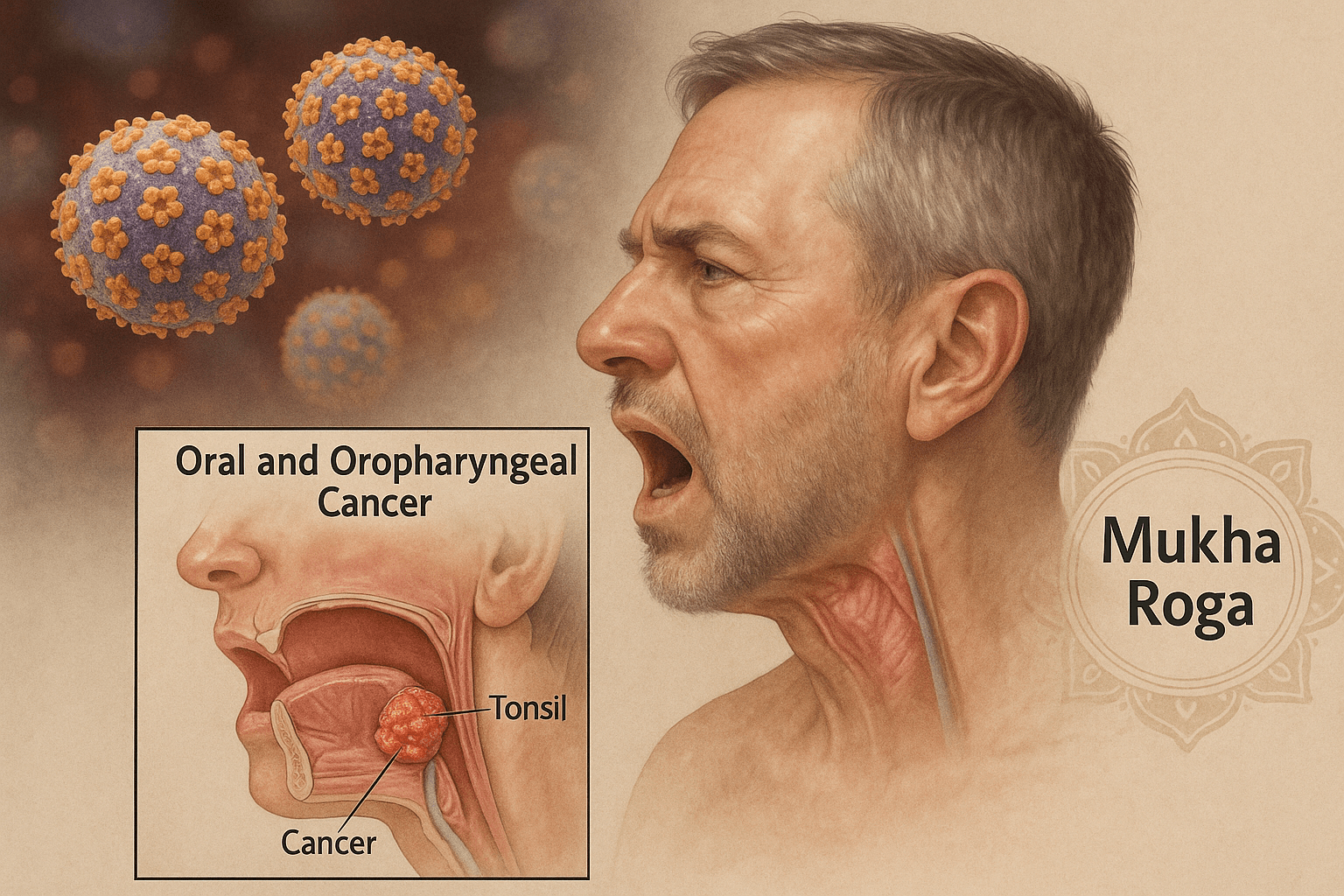

Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancers Linked to HPV

Role of HPV in Throat, Tonsil, and Tongue Cancers

In recent decades, HPV has emerged as a significant cause of oropharyngeal cancers, particularly those affecting the tonsils, base of the tongue, and throat. Unlike cervical cancer, which is almost exclusively associated with HPV-16 and HPV-18, oral and oropharyngeal cancers are most strongly linked to HPV-16 [16]. Viral integration at these sites disrupts epithelial cell regulation, leading to precancerous lesions and invasive cancers that often present later than cervical malignancies.

Risk Factors: Oral Sex, Tobacco, Alcohol, Weak Immunity

The transmission of HPV to the oral cavity often occurs through oral sexual practices [17]. However, not everyone exposed develops cancer—co-factors significantly influence risk. Tobacco smoking and heavy alcohol consumption act synergistically with HPV, accelerating malignant transformation [18]. Additionally, individuals with weakened immunity, such as those with HIV infection or undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, are more vulnerable to persistent oral HPV infections and their progression to cancer [19].

Symptoms and Progression

HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers often progress silently. Early symptoms can be subtle, leading to delayed diagnosis. Common signs include:

- Persistent sore throat or difficulty swallowing.

- Swollen lymph nodes in the neck.

- Voice changes or hoarseness.

- Pain or sores in the mouth that do not heal.

In advanced stages, these cancers may cause severe pain, difficulty eating, weight loss, and spread to regional lymph nodes. The slow and hidden onset is why many cases are detected only at advanced stages, worsening prognosis [20].

Ayurvedic Parallels: Mukha Roga and Shleshma Dushti

Ayurveda classifies disorders of the oral cavity under Mukha Roga (oral diseases). These include lesions, ulcers, foul odor, and growths that can be seen as early parallels to precancerous conditions [7]. Persistent infection and tissue overgrowth in the oral region also reflect Shleshma Dushti (derangement of Kapha dosha), which promotes abnormal cell proliferation and stagnation of fluids.

From an Ayurvedic standpoint, the combination of Krimi invasion (viral presence), Kapha aggravation, and weakened Agni (digestive/metabolic fire) creates a terrain favorable for chronic, hidden progression of oral disease into malignancy [8]. Holistic management involves cleansing therapies, strengthening immunity, and balancing Kapha to prevent progression from benign lesions to cancer.

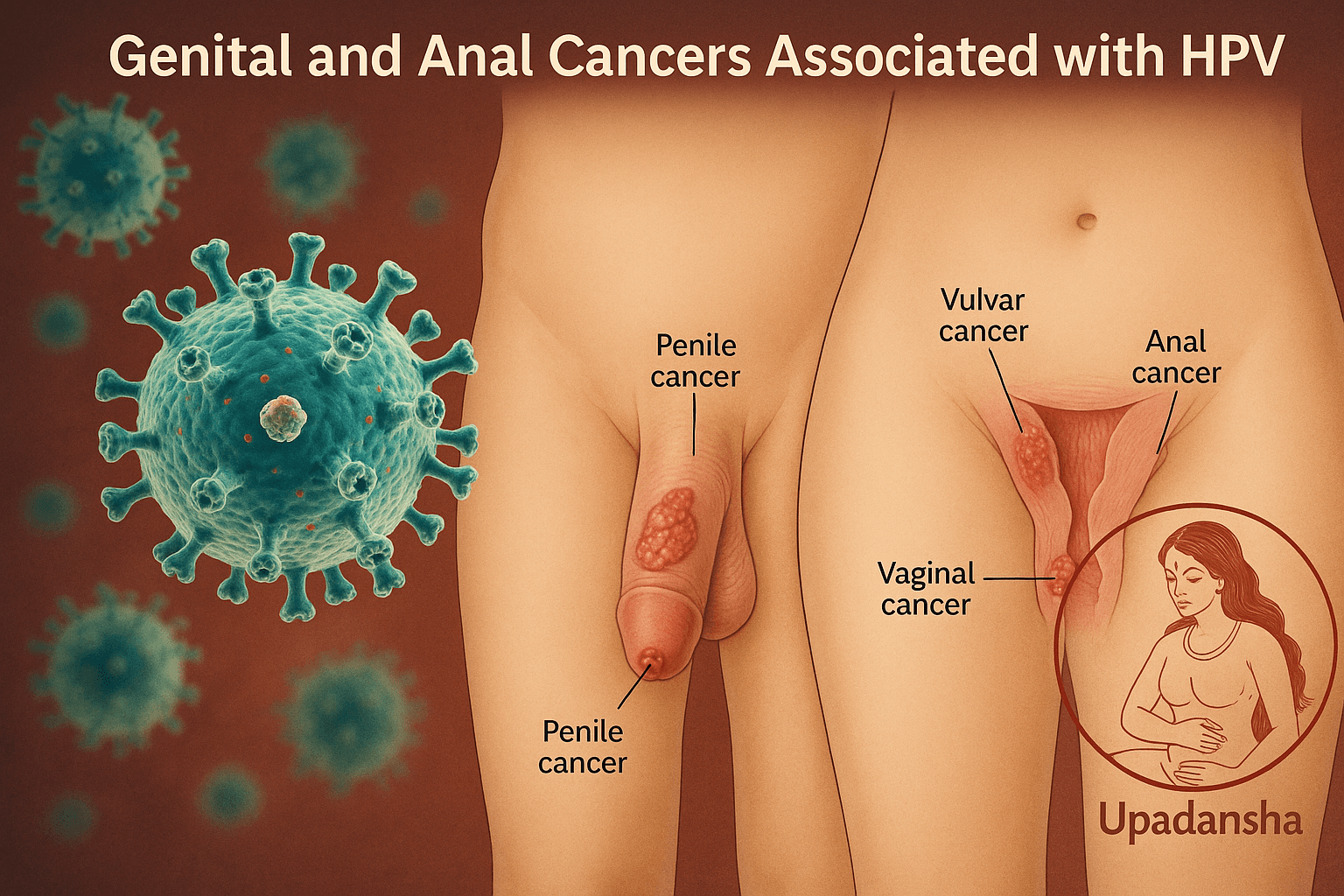

Genital and Anal Cancers Associated with HPV

Penile, Vulvar, Vaginal, and Anal Cancers

HPV infection is not limited to the cervix and oropharynx. Persistent infection with high-risk HPV types, particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18, has also been strongly linked to cancers of the penis, vulva, vagina, and anus [21]. These malignancies, although less common than cervical cancer, represent a significant global health burden. Anal cancer, for example, is increasing in incidence worldwide, particularly among specific high-risk groups.

High-Risk Populations (MSM, HIV-Positive Individuals)

Men who have sex with men (MSM) face disproportionately higher rates of HPV-related anal cancers, with studies showing the risk is especially elevated in those co-infected with HIV [22]. Immunosuppressed individuals, including transplant recipients and people living with HIV/AIDS, have reduced ability to clear persistent HPV infections, increasing the likelihood of malignant transformation [23]. This highlights the combined role of viral persistence and host immunity in shaping cancer risk.

Early Signs and Diagnostic Gaps

HPV-related genital and anal cancers often begin silently. Early warning signs may include:

- Small, painless lesions or warts in the genital or anal area.

- Persistent itching, discomfort, or bleeding.

- Pain during intercourse or defecation in more advanced cases.

Unfortunately, these signs are frequently overlooked or misdiagnosed as benign conditions. Screening programs for anal and penile cancers are far less developed than for cervical cancer, contributing to delayed detection and poorer outcomes [24].

Ayurvedic Mapping: Shukra Dhatu Dushti and Upadansha

In Ayurveda, genital infections and ulcerative conditions are described under Upadansha—a category of sexually transmitted disorders characterized by lesions, discharges, and discomfort in the genital region [7]. Persistent HPV infections leading to genital cancers mirror the classical description of Shukra Dhatu Dushti (vitiation of reproductive tissue), where chronic disturbances of sexual health and immunity manifest as deep-seated disease [25].

Moreover, Rakta-Shukra interaction plays a central role, as contamination of blood and reproductive channels (Shukravaha Srotas) allows pathogenic factors (Krimi) to lodge deeply and resist clearance. The Ayurvedic approach emphasizes purification (Shodhana), strengthening of reproductive tissue, and Rasayana therapies to restore vitality and prevent malignant progression.

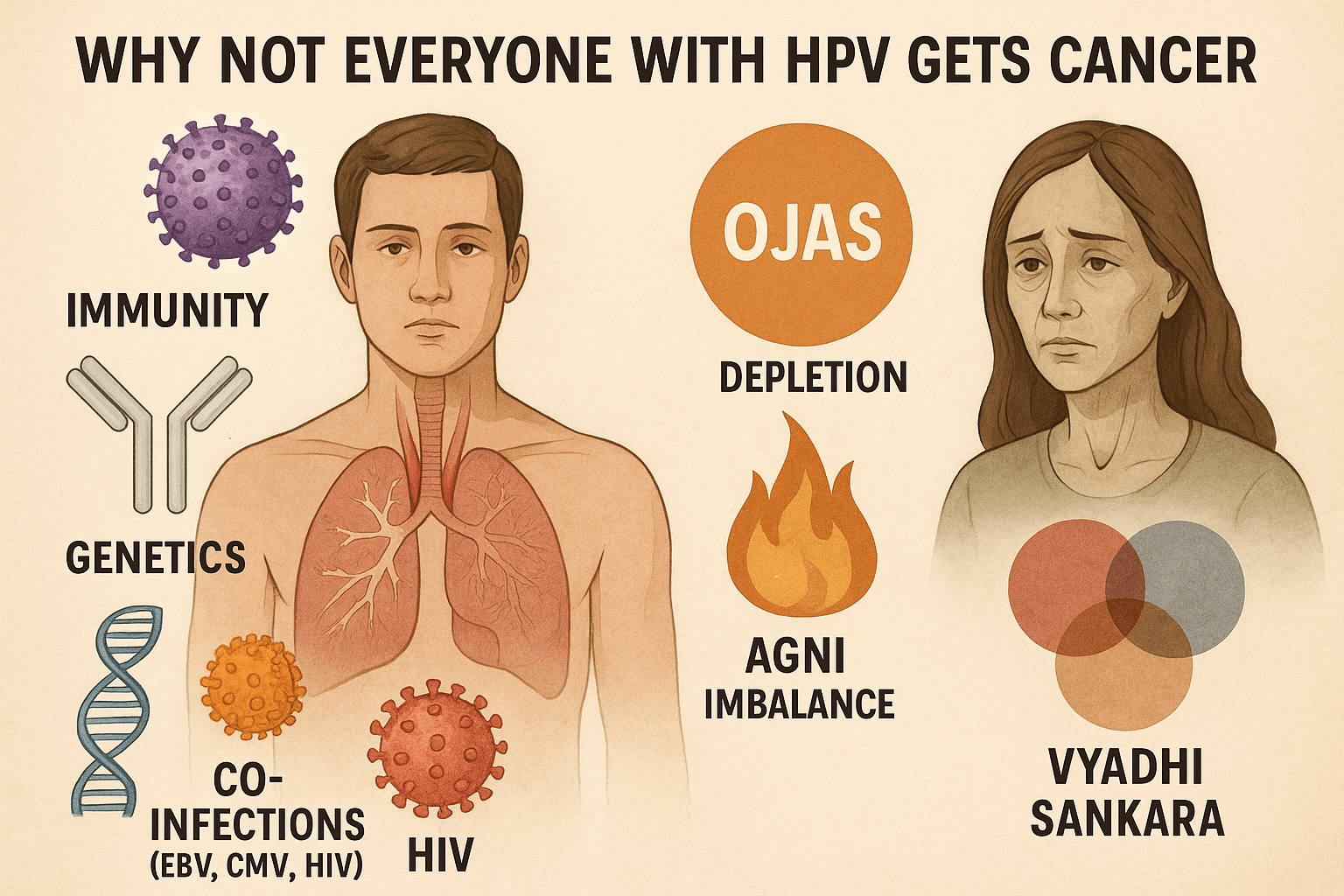

Why Not Everyone with HPV Gets Cancer

Role of Immunity, Genetics, and Co-Infections

Although HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection, the majority of infections never progress to cancer. Around 90% of HPV infections clear spontaneously within two years due to the body’s immune response [26]. The persistence and progression to malignancy occur only when specific risk factors converge.

- Immunity: A robust immune system plays the most crucial role in clearing HPV. Individuals with compromised immunity, such as those living with HIV/AIDS or undergoing long-term immunosuppressive therapy, are at far greater risk of persistent infection and cancer development [23].

- Genetics: Certain genetic polymorphisms in immune-regulating genes influence susceptibility to persistent HPV. Variations in HLA class I and II molecules have been linked to differences in how effectively individuals clear the virus [27].

- Co-infections: Co-infections with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), or HIV amplify cancer risk. EBV and CMV add additional oncogenic stress through chronic inflammation, while HIV significantly weakens host defenses, enabling HPV persistence and progression [28].

This interplay explains why not all HPV carriers develop cancer; host resilience, genetic makeup, and viral co-factors shape outcomes.

Ayurvedic View: Ojas Depletion, Agni Imbalance, Vyadhi Sankara

Ayurveda provides an integrated framework for understanding why certain individuals progress from infection to malignancy while others remain unaffected.

- Ojas depletion: Ojas, the essence of all Dhatus (tissues), represents immunity and vitality. Depletion of Ojas weakens the body’s ability to clear pathogenic influences such as Krimi (viruses) [29]. Individuals with low Ojas are more prone to persistent HPV infection and malignant transformation.

- Agni imbalance: Agni, the digestive and metabolic fire, governs cellular regulation and defense. Impaired Agni leads to accumulation of Ama (toxins), creating an internal environment conducive to HPV persistence and tissue disruption [30].

- Vyadhi Sankara: The concept of multiple disease overlap, or Vyadhi Sankara, closely parallels modern understanding of co-infections. When HPV co-exists with other pathogens (such as EBV or HIV), the compounded burden overwhelms the immune system, mirroring the Ayurvedic notion of simultaneous doshic aggravations leading to severe disease [31].

From this perspective, Ayurvedic healing aims not only at targeting HPV but also at restoring Ojas, balancing Agni, and addressing multi-infection complexity to prevent malignant transformation.

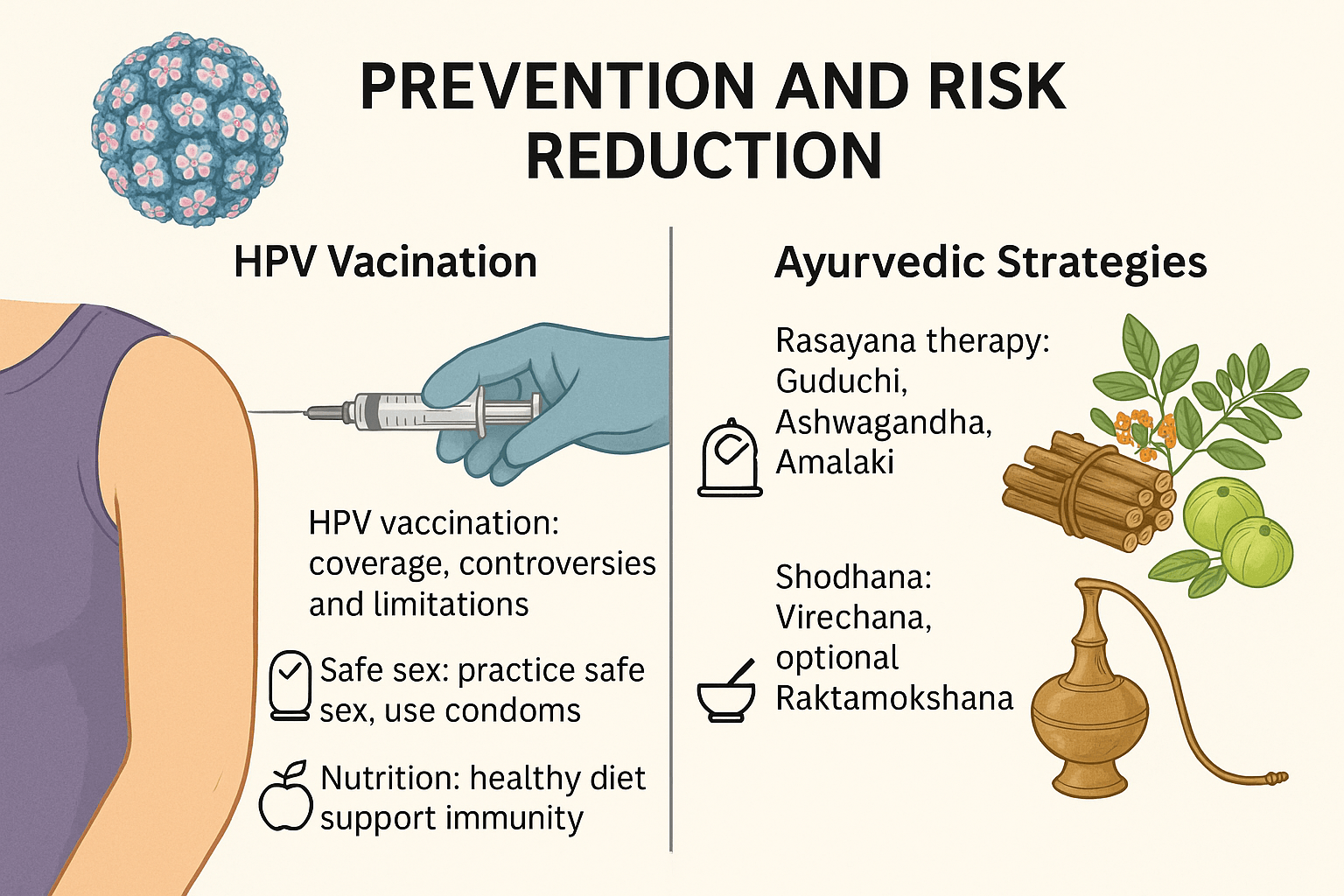

Prevention and Risk Reduction

HPV Vaccination: Coverage, Controversies, and Limitations

The HPV vaccine is widely recognized as one of the most effective preventive measures against HPV-related cancers. Current vaccines such as Gardasil-9 protect against the most common high-risk HPV types, including HPV-16 and HPV-18, and have demonstrated strong efficacy in reducing precancerous lesions and cervical cancer incidence [32].

However, challenges remain. Vaccine coverage is uneven across the globe, with low- and middle-income countries experiencing the lowest uptake due to high costs, supply issues, and lack of awareness [33]. Additionally, controversies around vaccine safety and the perception that vaccination promotes early sexual activity have slowed implementation in certain regions [34]. Importantly, vaccination does not protect against all oncogenic HPV strains, nor does it treat existing infections, highlighting the need for complementary strategies [35].

Lifestyle Factors: Safe Sex, Nutrition, and Immunity Support

Prevention extends beyond vaccination. Consistent condom use can lower HPV transmission risk, though it does not provide complete protection since HPV can spread through skin-to-skin contact [36]. Limiting the number of sexual partners and avoiding high-risk behaviors reduces exposure risk.

Nutritional status is also a key determinant. Diets rich in antioxidants, vitamins A, C, and E, and folate have been associated with lower HPV persistence and reduced progression to precancerous lesions [37]. Strengthening the immune system through regular exercise, stress management, and avoiding tobacco and alcohol further reduces risk.

Ayurvedic Strategies: Rasayana and Shodhana

Ayurveda emphasizes a holistic approach to prevention, focusing on strengthening body defenses and correcting systemic imbalances.

- Rasayana therapy: Herbs such as Guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia), Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera), and Amalaki (Emblica officinalis) act as immunomodulators, rejuvenators, and antioxidants, enhancing the body’s ability to resist persistent HPV infections [29].

- Shodhana therapies: Virechana (purgation) helps clear accumulated toxins from the body, while Raktamokshana (bloodletting, optional) is traditionally described for conditions involving Rakta Dushti (blood vitiation). These therapies aim to purify the internal environment, reducing the likelihood of viral persistence [30].

Through these combined measures—modern vaccination, lifestyle correction, and Ayurvedic Rasayana–Shodhana protocols—individuals can significantly lower their risk of HPV persistence and cancer progression.

Ayurvedic and Integrative Cure Approach

Root-Cause Healing Versus Symptom Suppression

Modern medicine focuses primarily on vaccination, screening, and treatment of precancerous lesions, but it does not provide a direct cure for HPV infection itself. In contrast, Ayurveda approaches the disease from the root, addressing the internal terrain of the body that allows persistent infection and malignant transformation. By correcting doshic imbalance, purifying Dhatus (tissues), and restoring Ojas (vital immunity), Ayurveda aims not only to manage symptoms but to eliminate the underlying cause.

Classical Formulations

Ayurvedic texts and clinical practice highlight several Rasayana and mineral formulations with antiviral and immunoregulatory potential. Among these, three stand out:

- Gandhak Rasayan: A sulfur-based Rasayana known for detoxification, immune enhancement, and antiviral activity.

- Swarna Bhasma: Gold calx, traditionally described as a rejuvenator, immunity booster, and regulator of deep tissue health.

- Vyadhiharan Rasayan: A specialized Rasayana designed to combat chronic, resistant diseases, aligning with the modern concept of eliminating persistent viral reservoirs.

These formulations, when administered in a personalized protocol, target the deep-seated pathology of HPV while rejuvenating systemic health.

Case-Based Insights and Holistic Lifestyle Guidelines

Clinical experience and patient case studies suggest that integrating Rasayana therapy with diet and lifestyle correction significantly improves outcomes. Stress reduction, balanced nutrition, detoxification therapies, and supportive yoga practices enhance immunity, creating an environment in which HPV cannot persist.

Explore the Complete Ayurvedic Cure

For a full step-by-step guide on how Ayurveda eliminates HPV at the root—covering herbs, minerals, Rasayana therapies, Panchakarma options, and lifestyle integration—please read our complete article here:

HPV: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Ayurvedic Cure

Pharma Focus on Vaccines and Palliative Care

The pharmaceutical industry has invested heavily in HPV vaccines and screening technologies, which indeed play a vital role in reducing the incidence of cervical and other cancers. However, this focus has created a narrative where prevention is equated solely with vaccination and detection. Treatment strategies in mainstream medicine remain largely palliative—removing abnormal tissue through surgical excision, cryotherapy, or laser ablation—without addressing the persistence of the virus itself [38]. This results in lifelong monitoring and repeated procedures, which are financially profitable but do not constitute a true cure.

Ignored Potential of Ayurvedic Medicine in Viral Eradication

Ayurveda, with its rich heritage of Rasayana and Shodhana therapies, provides a framework for addressing the root cause of HPV persistence. Classical texts describe conditions analogous to HPV-related lesions under Upadansha, Yoni Vyapad, and Mukha Roga, emphasizing purification, immune restoration, and tissue-specific rejuvenation [7]. Modern studies on Ayurvedic formulations such as Guduchi, Ashwagandha, Neem, and mineral preparations like Swarna Bhasma and Gandhak Rasayan demonstrate antiviral and immunomodulatory effects that align with viral clearance mechanisms [29].

Yet, despite promising insights, these approaches receive minimal attention in global healthcare systems. Pharmaceutical priorities often dictate research funding, leaving integrative strategies underexplored. The absence of large-scale clinical trials for Ayurvedic therapies is not necessarily due to inefficacy but rather to systemic neglect of non-patentable, traditional remedies [39].

The Future of Integrative Oncology

The way forward lies in bridging modern virology with Ayurvedic wisdom. By combining advanced screening and molecular insights with Rasayana-based immune restoration and detoxification, a new paradigm of integrative oncology can emerge. Such a system would not only focus on detecting and managing precancerous changes but also on eliminating persistent viral reservoirs and preventing malignant transformation.

This approach requires open-minded research collaborations, government policy shifts, and recognition that health should prioritize long-term healing rather than dependence on lifelong interventions. As awareness grows, the ignored potential of Ayurveda may form a cornerstone of a more holistic, sustainable model of cancer prevention and viral eradication [40].

FAQs

Does HPV always lead to cancer?

No. Most HPV infections clear naturally within one to two years through the body’s immune response. Only persistent infections with high-risk strains like HPV-16 or HPV-18 may progress to cancer over time.

Which cancers are most strongly linked to HPV?

HPV is most commonly associated with cervical cancer, but it can also cause oropharyngeal (throat, tonsil, tongue), anal, penile, vulvar, and vaginal cancers.

Can HPV be prevented with vaccination alone?

Vaccination significantly reduces the risk of infection with the most common high-risk HPV strains, but it does not cover all oncogenic types. It also cannot clear existing infections. Integrating lifestyle changes and holistic strategies is essential for full protection.

What are the early signs of HPV-related cancers?

Early stages are often silent. Warning signs may include abnormal vaginal bleeding, persistent sore throat, unexplained oral ulcers, or small growths in genital or anal areas. Because symptoms often appear late, regular screening is critical.

Who is at higher risk of HPV-related cancers?

Women with persistent high-risk HPV, men who have sex with men, HIV-positive individuals, immunocompromised patients, and those with multiple sexual partners or tobacco/alcohol habits are at higher risk.

How does Ayurveda explain HPV and cancer risk?

Ayurveda associates HPV-like conditions with Krimi (pathogenic organisms), Yoni Vyapad, Mukha Roga, and Upadansha. The progression toward cancer reflects imbalances in Rakta (blood), Shukra Dhatu (reproductive tissue), and depletion of Ojas (vital immunity).

Can Ayurveda cure HPV-related cancers?

Ayurvedic protocols focus on root-cause healing rather than symptom suppression. Through Rasayana therapy, Shodhana detoxification, and immune restoration, Ayurveda aims to eliminate viral persistence and rejuvenate tissues, reducing the risk of malignant transformation.

Is Panchakarma necessary for HPV treatment?

Panchakarma procedures such as Virechana or optional Raktamokshana may be recommended in specific cases, but they are not mandatory. Treatment is individualized based on the patient’s constitution and disease stage.

Should vaccinated individuals still consider Ayurvedic care?

Yes. Vaccination offers partial protection, but Ayurveda strengthens immunity, corrects imbalances, and addresses residual risk from strains not covered by vaccines. Combining both approaches provides the most comprehensive protection.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Genital HPV infection – Fact sheet. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm

- World Health Organization. (2022). Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer

- Schiffman, M., Castle, P. E., Jeronimo, J., Rodriguez, A. C., & Wacholder, S. (2007). Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. The Lancet, 370(9590), 890–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0

- Walboomers, J. M., Jacobs, M. V., Manos, M. M., Bosch, F. X., Kummer, J. A., Shah, K. V., … & Muñoz, N. (1999). Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. The Journal of Pathology, 189(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F

- Moody, C. A., & Laimins, L. A. (2010). Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: Pathways to transformation. Nature Reviews Cancer, 10(8), 550–560. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2886

- Doorbar, J. (2006). Molecular biology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer. Clinical Science, 110(5), 525–541. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20050369

- Sushruta. Sushruta Samhita, Nidana Sthana 6/25–30. In Jadavji Trikamji (Ed.), Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan, Varanasi.

- Charaka. Charaka Samhita, Chikitsa Sthana 30/174–179. In Jadavji Trikamji (Ed.), Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan, Varanasi.

- Arbyn, M., Weiderpass, E., Bruni, L., de Sanjosé, S., Saraiya, M., Ferlay, J., & Bray, F. (2020). Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: A worldwide analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 8(2), e191–e203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30482-6

- Singh, R. H. (2009). Exploring issues in the development of Ayurvedic research methodology. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, 1(1), 91–95. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-9476.59826

- Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660

- Bruni, L., Albero, G., Serrano, B., Mena, M., Gómez, D., Muñoz, J., … & de Sanjosé, S. (2021). ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases Report. https://hpvcentre.net

- Cancer Research UK. (2022). Cervical cancer symptoms. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cervical-cancer/symptoms

- Ronco, G., Dillner, J., Elfström, K. M., Tunesi, S., Snijders, P. J., Arbyn, M., … & Segnan, N. (2014). Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomized controlled trials. The Lancet, 383(9916), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7

- Bhavaprakasha. Bhavaprakasha Samhita, Madhyama Khanda, Yonivyapad Chikitsa Adhyaya. In Chunekar, K. C. (Ed.), Chaukhamba Bharati Academy, Varanasi.

- Chaturvedi, A. K., Engels, E. A., Pfeiffer, R. M., Hernandez, B. Y., Xiao, W., Kim, E., … & Gillison, M. L. (2011). Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29(32), 4294–4301. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596

- D’Souza, G., Kreimer, A. R., Viscidi, R., Pawlita, M., Fakhry, C., Koch, W. M., … & Gillison, M. L. (2007). Case–control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 356(19), 1944–1956. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa065497

- Hashibe, M., Brennan, P., Benhamou, S., Castellsague, X., Chen, C., Curado, M. P., … & Boffetta, P. (2007). Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: Pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 99(10), 777–789. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djk179

- Beachler, D. C., D’Souza, G., Sugar, E. A., Xiao, W., Gillison, M. L., & Engels, E. A. (2013). Natural history of anal vs oral HPV infection in HIV-infected men and women. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 208(2), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jit163

- Fakhry, C., & Gillison, M. L. (2006). Clinical implications of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(17), 2606–2611. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1291

- Alemany, L., Saunier, M., Alvarado-Cabrero, I., Quirós, B., Salmerón, J., Shin, H. R., … & de Sanjosé, S. (2015). Human papillomavirus DNA prevalence and type distribution in anal carcinomas worldwide. International Journal of Cancer, 136(1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28963

- Machalek, D. A., Poynten, I. M., Jin, F., Fairley, C. K., Farnsworth, A., Garland, S. M., … & Grulich, A. E. (2012). Anal human papillomavirus infection and associated neoplastic lesions in men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology, 13(5), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70080-3

- Clifford, G. M., Polesel, J., Rickenbach, M., Dal Maso, L., Keiser, O., Kofler, A., … & Franceschi, S. (2008). Cancer risk in the Swiss HIV cohort study: Associations with immunodeficiency, HIV, and other risk factors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 100(12), 884–893. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djn176

- Frisch, M., Fenger, C., van den Brule, A. J., Sørensen, P., Meijer, C. J., Walboomers, J. M., & Melbye, M. (1999). Variants of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus and their relation to human papillomaviruses. Cancer Research, 59(3), 753–757. https://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/59/3/753

- Vagbhata. Ashtanga Hridaya, Nidana Sthana 5/18–22. In Harisastri Paradakara (Ed.), Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan, Varanasi.

- Stanley, M. (2010). Pathology and epidemiology of HPV infection in females. Gynecologic Oncology, 117(2 Suppl), S5–S10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.024

- Hildesheim, A., Wang, S. S., Hosttler, A. J., Shields, T. S., Bratti, M. C., Sherman, M. E., … & Schiffman, M. (2001). Genetic polymorphisms in immune and DNA repair genes and risk of cervical cancer: A population-based study. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 10(12), 1219–1224. https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/10/12/1219

- Mesri, E. A., Feitelson, M. A., & Munger, K. (2014). Human viral oncogenesis: A cancer hallmarks analysis. Cell Host & Microbe, 15(3), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.011

- Balasubramani, S. P., Mohan, J., Chatterjee, S., Patra, S., & Puri, S. (2020). Immunomodulatory herbal plants and their applications: An overview. Phytomedicine, 76, 153281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153281

- Sharma, P. V. (1996). Dravyaguna Vijnana (Vol. 2). Chaukhamba Bharati Academy, Varanasi.

- Shastri, K. (Ed.). (2016). Charaka Samhita, Nidana Sthana, Vyadhi Sankara Adhyaya. Chaukhamba Orientalia, Varanasi.

- Drolet, M., Bénard, É., Pérez, N., Brisson, M., Ali, H., Boily, M. C., … & Brisson, J. (2019). Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 394(10197), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30298-3

- Gallagher, K. E., LaMontagne, D. S., & Watson-Jones, D. (2018). Status of HPV vaccine introduction and barriers to country uptake. Vaccine, 36(32), 4761–4767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.003

- Harper, D. M., & DeMars, L. R. (2017). HPV vaccines – A review of the first decade. Gynecologic Oncology, 146(1), 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.04.004

- Joura, E. A., Giuliano, A. R., Iversen, O. E., Bouchard, C., Mao, C., Mehlsen, J., … & Luxembourg, A. (2015). A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(8), 711–723. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1405044

- Winer, R. L., Hughes, J. P., Feng, Q., O’Reilly, S., Kiviat, N. B., Holmes, K. K., & Koutsky, L. A. (2006). Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(25), 2645–2654. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa053284

- Giuliano, A. R., Papenfuss, M., Nour, M., Canfield, L. M., Schneider, A., Hatch, K., & Baldwin, S. (1997). Antioxidant nutrients: Associations with persistent human papillomavirus infection. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 6(11), 917–923. https://cebp.aacrjournals.org/content/6/11/917

- Kyrgiou, M., Athanasiou, A., Paraskevaidi, M., Mitra, A., Kalliala, I. E., Martin-Hirsch, P. P., … & Arbyn, M. (2017). Adverse obstetric outcomes after local treatment for cervical preinvasive and early invasive disease according to cone depth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 354, i3633. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3633

- Patwardhan, B., Mutalik, G., & Tillu, G. (2015). Integrative Approaches for Health: Biomedical Research, Ayurveda and Yoga. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2013-0-13072-2

- Green, J. (2015). Integrative oncology and global health: Opportunities for collaboration. Journal of Global Oncology, 1(2), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.2015.000802