- IBS at a Glance (Prevalence & Burden)

- Understanding IBS as a Functional Gut Disorder

- Common Symptoms of IBS

- Types of IBS

- What Causes IBS

- How IBS Is Diagnosed

- IBS Versus Other Digestive Diseases

- Is IBS Serious or Dangerous

- Treatment Overview for IBS

- Diet and Lifestyle Role in IBS

- FAQs(Frequently Asked Question)

- REFERENCE LIST

What Is IBS? (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) – is a functional gastrointestinal disorder, meaning it is defined by a consistent pattern of symptoms arising from altered gut function rather than visible structural damage or inflammation on routine investigations [1]. In IBS, the intestines appear normal on endoscopy, imaging, and standard laboratory tests, yet patients experience real and often debilitating symptoms due to disturbances in gut motility, visceral sensitivity, and gut–brain communication.

IBS is globally recognized as one of the most common chronic digestive disorders, affecting populations across North America, Europe, Asia, and other regions, with significant impact on quality of life and healthcare utilization [2]. It is classified and diagnosed internationally using standardized symptom-based criteria, reflecting broad medical consensus rather than regional or alternative interpretations.

At its core, IBS is a symptom-based condition, characterized primarily by recurrent abdominal pain associated with changes in bowel habits such as constipation, diarrhea, or a mixture of both [1]. This symptom-focused definition is central to modern gastroenterology and explains why IBS requires careful clinical evaluation rather than reliance on a single test or scan.

IBS at a Glance (Prevalence & Burden)

Irritable Bowel Syndrome is among the most common chronic gastrointestinal disorders worldwide, with population studies estimating that approximately 5 to 10 percent of adults meet diagnostic criteria, depending on geographic region and diagnostic methods used [2]. Prevalence rates vary across countries, partly due to differences in healthcare access, symptom reporting, and diagnostic awareness. Many individuals with IBS remain undiagnosed, either because symptoms are normalized, stigmatized, or attributed to diet or stress alone, suggesting that the true global burden is likely underestimated.

The impact of IBS extends far beyond digestive discomfort. Research consistently demonstrates a marked reduction in quality of life among affected individuals, including limitations in daily activities, work productivity, social engagement, and psychological well-being [3]. Patients often describe persistent anxiety related to unpredictable bowel habits, fear of symptom flare-ups in public settings, and difficulty maintaining normal routines involving travel, meals, or professional commitments. These factors contribute to emotional distress and reinforce the chronic nature of the condition.

From a healthcare systems perspective, IBS imposes a substantial clinical and economic burden. It is a leading cause of repeated primary care visits, gastroenterology referrals, diagnostic testing, and long-term medication use [2][3]. Despite normal test results, patients frequently undergo multiple investigations in search of reassurance, increasing healthcare costs without necessarily improving outcomes. This pattern highlights the importance of early recognition, accurate diagnosis, and patient-centered education to reduce unnecessary testing and focus care on effective symptom control and long-term disease understanding.

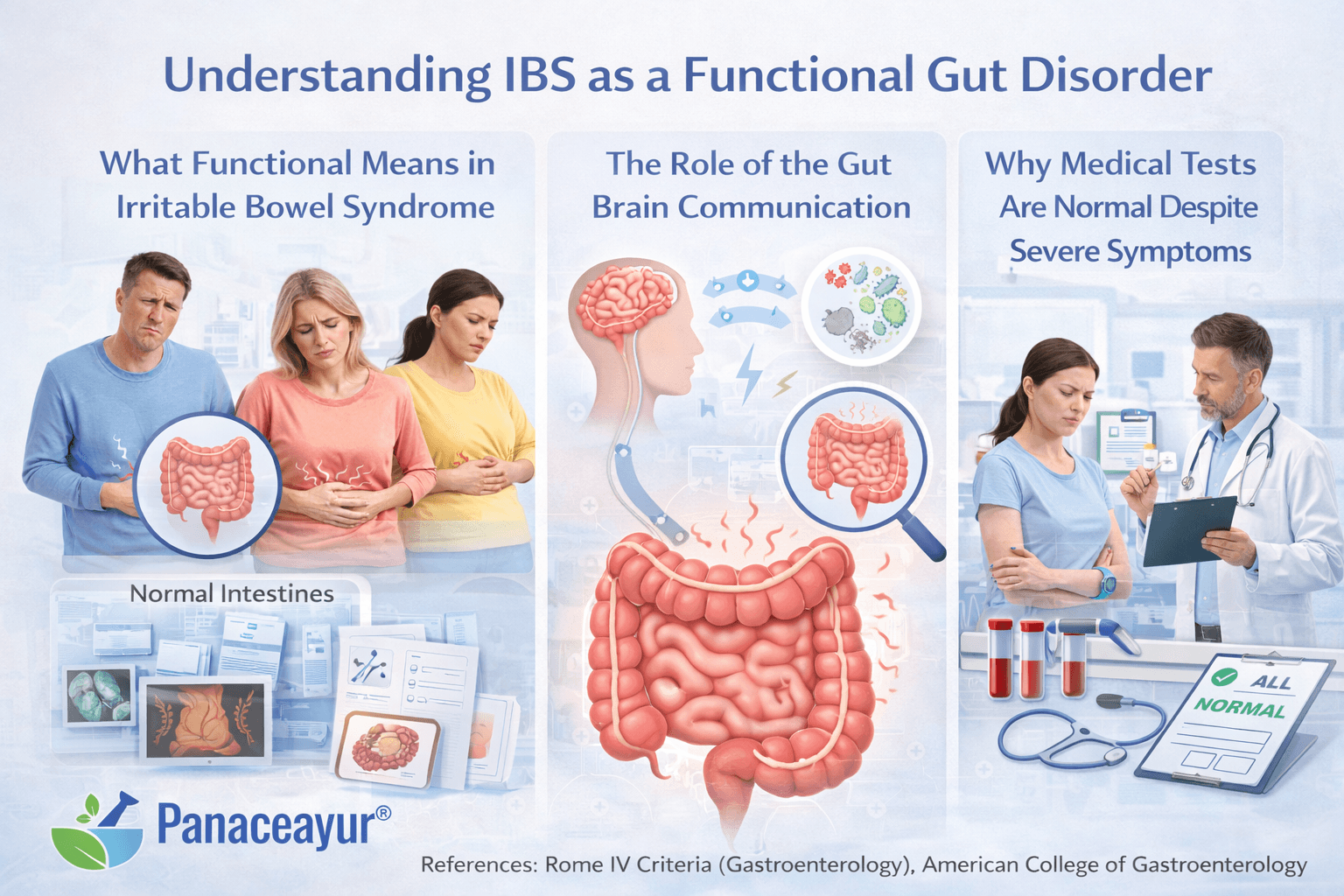

Understanding IBS as a Functional Gut Disorder

What Functional Means in Irritable Bowel Syndrome

When we describe Irritable Bowel Syndrome as a functional gut disorder, we are explaining the nature of the problem rather than minimizing it. In functional disorders, the structure of the digestive organs remains intact, but their performance becomes abnormal. Unlike conditions such as ulcers, tumors, or inflammatory bowel disease, IBS does not show visible damage on scans, endoscopy, or routine laboratory testing. Yet the symptoms are real, persistent, and often disabling. From a third person medical perspective, this distinction is essential because it defines how IBS should be diagnosed and treated, and why conventional investigations often fail to provide answers [1].

From a first person perspective, many patients describe frustration after being told that all tests are normal while their daily life continues to be disrupted by pain, bloating, and unpredictable bowel habits. From a second person perspective, if you are experiencing these symptoms, it is important to understand that normal test results do not mean your condition is imagined or insignificant. IBS represents a disorder of function, not a lack of disease, and this concept is well established in modern gastroenterology [1].

The Role of the Gut Brain Axis

A central feature of IBS is disturbance in the gut brain axis, the communication network that connects the digestive system with the brain and nervous system. This pathway regulates bowel movement, pain perception, immune responses, and stress adaptation. In IBS, signaling between the gut and brain becomes hypersensitive and poorly regulated. As a result, sensations that would normally be ignored, such as mild gas movement or routine intestinal contractions, are perceived as painful or urgent [4].

From a third person scientific viewpoint, this altered communication explains why IBS symptoms often worsen during emotional stress, anxiety, or sleep disruption. From a first person experience, patients may notice that symptoms flare during exams, work pressure, travel, or emotional strain. From a second person standpoint, you may recognize that stress does not cause IBS by itself, but it strongly amplifies symptoms through this disrupted gut brain communication. This understanding shifts IBS away from outdated psychological labels and places it firmly within neurogastroenterology [4].

Why Medical Tests Are Normal Despite Severe Symptoms

One of the defining features of IBS is the mismatch between symptom severity and objective test findings. Blood tests, imaging studies, colonoscopy, and biopsies are typically normal because they are designed to detect structural damage, inflammation, or infection. IBS does not produce these changes. Instead, it alters gut motility, sensory thresholds, and nervous system responses, which are not captured by routine diagnostics [1].

From a third person clinical perspective, this is why IBS is diagnosed using symptom based criteria rather than laboratory confirmation. From a first person viewpoint, patients often feel invalidated when results come back normal, despite ongoing discomfort. From a second person perspective, understanding this mechanism can prevent unnecessary fear and repeated testing. Normal investigations are not a failure of diagnosis but a defining characteristic of functional gut disorders like IBS. Recognizing this helps guide appropriate treatment strategies focused on restoring gut function, neural regulation, and symptom control rather than chasing nonexistent structural disease [1].

Common Symptoms of IBS

Abdominal Pain and Discomfort

Abdominal pain is the core symptom of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and is essential for making a clinical diagnosis. From a third person medical standpoint, IBS related pain is typically linked to bowel activity and is often relieved, partially or completely, after passing stool. The pain does not arise from tissue damage or inflammation but from altered gut sensitivity and abnormal intestinal contractions [1].

From a first person perspective, patients often describe this pain as cramping, squeezing, burning, or a deep aching sensation that can vary in intensity from mild discomfort to severe episodes that interfere with daily life. From a second person perspective, you may notice that the pain shifts location, changes with meals, stress, or bowel movements, and lacks a fixed anatomical point. This variability is a hallmark of IBS and distinguishes it from structural gastrointestinal diseases [5].

Bloating and Abdominal Distension

Bloating is one of the most distressing and socially limiting symptoms of IBS. Clinically, bloating occurs due to abnormal gut motility, altered gas handling, and increased visceral sensitivity rather than excess gas production alone [1]. Objective studies show that many IBS patients experience visible abdominal distension by the end of the day, even when imaging shows no obstruction or pathology.

From a first person experience, patients frequently report a sensation of fullness, tightness, or pressure that worsens after meals and improves overnight. From a second person perspective, you may feel uncomfortable in fitted clothing, avoid social situations, or feel frustrated when bloating appears disproportionate to what you have eaten. This symptom often fluctuates with hormonal changes, stress levels, and dietary triggers, reinforcing the functional nature of IBS [5].

Altered Bowel Habits

Changes in bowel habits form another defining feature of IBS and are used to classify its subtypes. From a clinical viewpoint, these changes include constipation, diarrhea, or an alternating pattern of both, without evidence of structural disease [1]. Stool frequency, consistency, and urgency may all vary over time.

From a first person standpoint, patients may experience days of hard, difficult bowel movements followed by sudden loose stools, or frequent urgency without complete evacuation. From a second person perspective, you may feel anxious about access to restrooms, experience incomplete relief after defecation, or notice mucus in the stool. These patterns reflect dysregulated gut motility and sensory signaling rather than infection or inflammation [5].

Extraintestinal Symptoms Associated With IBS

IBS is not limited to the digestive tract and often presents with symptoms affecting other systems of the body. From a third person medical perspective, common extraintestinal symptoms include fatigue, headaches, sleep disturbances, pelvic discomfort, urinary frequency, and heightened anxiety or low mood [5]. These symptoms reflect shared neural and immune pathways between the gut and other organ systems.

From a first person experience, patients often report feeling exhausted even after adequate rest or notice that digestive flare ups coincide with mental stress or emotional strain. From a second person perspective, you may wonder why symptoms seem widespread rather than confined to the abdomen. This systemic presentation further supports IBS as a disorder of gut brain interaction rather than a localized intestinal disease [1].

Symptom Triggers and Daily Fluctuation

IBS symptoms rarely remain constant throughout the day, and their fluctuating nature is one of the defining features of the disorder. From a third person clinical perspective, symptoms often intensify after meals due to altered gut motility and heightened visceral sensitivity. Normal digestive responses such as intestinal contractions or gas movement can trigger pain, bloating, or urgency in individuals with IBS, even when the same meals cause no discomfort in others [1].

From a first person experience, many patients notice that symptoms are worse in the morning, after eating, or during periods of emotional stress. From a second person perspective, you may recognize that stressful events, poor sleep, travel, or hormonal changes can suddenly worsen bowel habits or abdominal discomfort. These fluctuations occur because the gut brain communication system responds dynamically to psychological and physiological stimuli. This explains why IBS symptoms can improve on some days and worsen on others without any detectable structural change in the intestine [5].

Symptoms That Require Further Evaluation

While IBS causes significant discomfort, it does not produce certain warning signs that suggest structural or inflammatory disease. From a third person medical standpoint, symptoms such as unexplained weight loss, persistent fever, blood in the stool, anemia, or diarrhea that awakens a person from sleep are not characteristic of IBS and require further evaluation [1].

From a first person perspective, patients may worry that ongoing abdominal pain signals a serious illness. From a second person perspective, it is important for you to understand that IBS symptoms are typically chronic but stable in pattern. A sudden change in symptom character, severity, or associated systemic signs should prompt medical review. This distinction protects patients from delayed diagnosis of other conditions while reinforcing confidence when IBS criteria are clearly met. Clarifying what IBS does not cause is an essential part of responsible patient education and clinical safety [5].

Types of IBS

Irritable Bowel Syndrome is not a single uniform condition. From a third person clinical perspective, IBS is classified into different types based on the dominant bowel habit observed over time. This classification helps clinicians understand symptom patterns, guide dietary and lifestyle strategies, and set realistic expectations for patients, even though the underlying disorder of gut function remains the same across all types [1].

IBS With Predominant Constipation

IBS with predominant constipation is characterized by infrequent bowel movements, hard or pellet like stools, and difficulty with evacuation. From a first person experience, patients often describe prolonged straining, a sense of blockage, and abdominal discomfort that improves only partially after passing stool. From a second person perspective, you may notice that bloating and abdominal heaviness worsen when bowel movements are delayed for several days. Clinically, this pattern reflects slowed intestinal transit and altered nerve signaling rather than mechanical obstruction or disease [5].

IBS With Predominant Diarrhea

IBS with predominant diarrhea involves frequent loose or watery stools, urgency, and a fear of sudden bowel movements. From a third person medical standpoint, these symptoms occur without infection, inflammation, or intestinal damage. From a first person experience, patients commonly report an urgent need to use the restroom after meals or during stressful situations. From a second person perspective, you may recognize that symptoms fluctuate, with some days appearing nearly normal and others marked by repeated urgency. This variability is a hallmark of functional bowel dysregulation [1].

IBS With Mixed Bowel Habits

IBS with mixed bowel habits includes alternating periods of constipation and diarrhea. From a clinical viewpoint, this type often causes the greatest frustration because symptoms appear inconsistent and unpredictable. From a first person perspective, patients may feel confused by rapid shifts in bowel patterns. From a second person standpoint, you may notice that stress, dietary changes, or hormonal fluctuations trigger transitions between constipation and diarrhea. This pattern reflects unstable gut motility and heightened sensory responsiveness rather than multiple coexisting diseases [5].

Unclassified IBS Pattern

Some individuals experience IBS symptoms that do not consistently fit into one dominant bowel pattern. From a third person perspective, this unclassified pattern is recognized when symptom profiles vary widely over time. From a first person experience, patients may feel that their symptoms do not match standard descriptions. From a second person perspective, it is important to understand that this variability still falls within the IBS spectrum and does not invalidate the diagnosis. Symptom focused evaluation and individualized management remain appropriate [1].

What Causes IBS

Irritable Bowel Syndrome does not arise from a single cause. From a third person medical perspective, IBS develops due to a complex interaction between the nervous system, digestive tract, immune signaling, and environmental influences. This multifactorial origin explains why no single test can identify IBS and why symptoms vary widely between individuals [4].

Disrupted Gut Brain Communication

One of the most important drivers of IBS is altered communication between the gut and the brain. From a clinical standpoint, the gut and nervous system constantly exchange signals that regulate bowel movement, pain perception, digestion, and stress responses. In IBS, this signaling becomes hypersensitive and poorly regulated. Normal digestive events such as bowel contractions or gas movement are interpreted as painful or urgent [4].

From a first person experience, patients often describe feeling that their gut overreacts to routine activities like eating or emotional stress. From a second person perspective, you may notice that anxiety, anticipation, or pressure situations immediately trigger abdominal pain or bowel urgency. This mechanism places IBS within the field of disorders of gut brain interaction rather than structural disease.

Visceral Hypersensitivity and Altered Motility

Another central factor in IBS is visceral hypersensitivity, which refers to increased sensitivity of the intestinal nerves. From a third person scientific perspective, IBS patients have a lower threshold for pain in response to normal intestinal stretching or movement. This heightened sensitivity occurs without tissue injury or inflammation [7].

From a first person viewpoint, patients may experience discomfort or pain after eating small meals or during mild bloating that would not affect others. From a second person perspective, you may feel pain that seems disproportionate to physical findings. At the same time, intestinal motility may become irregular, leading to constipation, diarrhea, or alternating bowel habits. These changes reflect nervous system dysregulation rather than blockage or infection [7].

Dietary Triggers and Digestive Sensitivity

Diet plays a significant role in triggering IBS symptoms, although it is not the root cause. From a third person clinical perspective, certain carbohydrates and fibers can increase intestinal distension or alter gut signaling, provoking symptoms in sensitive individuals. This reaction does not indicate food allergy or intolerance in the classical sense, but rather an exaggerated digestive response [11].

From a first person experience, patients often identify specific meals that worsen bloating, pain, or bowel urgency. From a second person perspective, you may notice that symptom severity depends more on meal composition, timing, and portion size than on a single forbidden food. This explains why rigid dietary elimination often fails unless combined with broader gut regulation strategies [11].

Stress, Hormonal, and Immune Influences

Stress does not cause IBS by itself, but it strongly influences symptom severity. From a third person medical standpoint, stress hormones directly affect gut motility, pain perception, and intestinal permeability. Hormonal fluctuations, particularly in women, can further amplify symptoms through nervous system sensitivity [4].

From a first person perspective, patients frequently report symptom flares during emotionally demanding periods or hormonal changes. From a second person viewpoint, understanding this link helps explain why symptoms may worsen during stress even when diet remains unchanged. Low grade immune activation and prior gastrointestinal infections may also sensitize gut pathways, allowing symptoms to persist long after the initial trigger has resolved [7].

Why IBS Persists Without Structural Disease

IBS often persists because the nervous system and gut remain locked in a sensitized state. From a third person perspective, repeated symptom cycles reinforce abnormal signaling patterns between the brain and intestine. From a first person experience, patients may feel trapped in recurring symptoms despite reassurance that tests are normal. From a second person perspective, recognizing IBS as a disorder of function rather than damage helps shift focus toward restoring regulation rather than searching for a missing disease [4].

How IBS Is Diagnosed

Diagnosing Irritable Bowel Syndrome requires a careful clinical approach rather than reliance on a single laboratory or imaging test. From a third person medical perspective, IBS is a positive diagnosis, meaning it is identified based on well defined symptom patterns rather than by exclusion alone. Modern gastroenterology recognizes that repeated testing without clinical direction delays care and increases patient anxiety [1].

Symptom Based Diagnostic Criteria

The accepted standard for diagnosing IBS is the Rome IV criteria. These criteria focus on recurrent abdominal pain associated with bowel movements or changes in stool frequency or stool form, present over a defined period. From a third person standpoint, this framework reflects decades of research showing that IBS follows consistent symptom patterns even when structural disease is absent [1].

From a first person experience, many patients feel relieved when symptoms finally fit into a recognized medical diagnosis rather than being labeled unexplained. From a second person perspective, if your symptoms meet these criteria, a diagnosis of IBS can be made confidently without endless investigations. This symptom based approach validates patient experience while avoiding unnecessary procedures.

Role of Medical History and Clinical Evaluation

A thorough medical history is central to IBS diagnosis. From a third person clinical perspective, doctors evaluate symptom duration, relationship to meals, bowel habit patterns, stress influence, and previous gastrointestinal infections. This information often provides more diagnostic clarity than advanced testing [6].

From a first person perspective, patients may not realize that details such as timing of pain relief after bowel movements or variability of stool consistency are diagnostically important. From a second person viewpoint, sharing clear symptom patterns with your clinician helps reach a diagnosis faster and reduces diagnostic uncertainty.

Tests Used to Exclude Other Conditions

Although IBS itself does not produce abnormal test results, limited investigations are often performed to exclude other diseases that can mimic IBS. From a third person standpoint, blood tests may be used to rule out anemia, inflammation, thyroid dysfunction, or celiac disease. Stool tests may exclude infection or inflammatory conditions when symptoms suggest risk [6].

From a first person experience, patients sometimes feel frustrated when tests return normal despite severe symptoms. From a second person perspective, understanding that normal results support the IBS diagnosis rather than contradict it can prevent unnecessary fear. These tests are not meant to find IBS directly but to ensure that no structural or inflammatory disease is present.

Why Extensive Testing Is Usually Unnecessary

Routine use of repeated imaging, colonoscopy, or advanced diagnostics is not recommended in the absence of warning signs. From a third person medical perspective, excessive testing does not improve outcomes and may reinforce symptom focused anxiety. IBS is a disorder of gut function and nervous system regulation, not a condition that progresses to visible tissue damage [1].

From a first person viewpoint, repeated testing may increase stress and symptom awareness. From a second person perspective, accepting a clinical diagnosis allows attention to shift toward management and quality of life improvement rather than continued diagnostic pursuit.

Importance of Red Flag Symptom Assessment

While IBS itself is benign, clinicians remain vigilant for symptoms that suggest alternative diagnoses. From a third person perspective, unexplained weight loss, persistent fever, blood in stool, anemia, or symptoms that awaken a person from sleep require further evaluation [6].

From a first person experience, patients may fear that serious disease is being missed. From a second person standpoint, knowing that these warning signs are actively assessed during diagnosis provides reassurance that IBS is not diagnosed casually but responsibly.

IBS Versus Other Digestive Diseases

IBS is frequently confused with other digestive conditions because many gastrointestinal disorders share overlapping symptoms. From a third person medical perspective, distinguishing IBS from structural or inflammatory diseases is essential to avoid misdiagnosis, unnecessary treatment, and patient anxiety. IBS is defined by altered gut function and sensory processing, while other digestive diseases involve visible pathology, inflammation, infection, or biochemical abnormalities [6].

IBS Versus Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel disease includes conditions such as Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, which cause chronic inflammation and tissue damage in the intestines. From a clinical standpoint, inflammatory bowel disease produces objective findings such as elevated inflammatory markers, abnormal imaging, mucosal damage on endoscopy, and sometimes bleeding or anemia [6].

From a first person perspective, patients with IBS may worry that persistent pain or diarrhea indicates inflammatory bowel disease. From a second person viewpoint, it is important to understand that IBS does not cause intestinal inflammation, ulcers, or progressive bowel damage. Symptoms in IBS fluctuate but do not lead to structural injury. This distinction allows reassurance once inflammatory causes have been appropriately excluded [9].

IBS Versus Food Intolerance and Allergy

Food intolerance and food allergy are often confused with IBS because symptoms may appear after eating. From a third person medical perspective, true food allergy involves immune mediated reactions and may present with hives, swelling, breathing difficulty, or systemic responses. Food intolerance typically produces predictable symptoms after ingestion of specific substances such as lactose [5].

From a first person experience, patients with IBS often report sensitivity to multiple foods rather than a single trigger. From a second person perspective, this pattern reflects heightened gut sensitivity rather than a specific immune reaction. IBS symptoms depend more on meal composition, portion size, and digestive load than on one offending food. This explains why strict elimination diets rarely provide lasting relief when used alone [11].

IBS Versus Chronic Infection or Parasites

Chronic intestinal infections can mimic IBS symptoms, especially diarrhea and abdominal discomfort. From a third person standpoint, infections typically produce abnormal stool tests, systemic symptoms, or persistent inflammation. Once infections are excluded through appropriate evaluation, ongoing symptoms are unlikely to be infectious in nature [6].

From a first person perspective, patients may fear that an untreated infection is causing symptoms. From a second person perspective, understanding that IBS does not involve ongoing infection helps prevent repeated antibiotic use, which can worsen gut sensitivity and prolong symptoms.

Why Accurate Differentiation Matters

Correctly distinguishing IBS from other digestive diseases allows appropriate management and prevents harm. From a third person medical perspective, mislabeling IBS as inflammatory or infectious disease leads to unnecessary medications and procedures. From a first person experience, clarity reduces fear and frustration. From a second person viewpoint, a confident diagnosis enables focus on functional recovery rather than continued diagnostic uncertainty [6].

Is IBS Serious or Dangerous

Is IBS a Life Threatening Condition

From a third person medical perspective, Irritable Bowel Syndrome is not a life threatening disease. It does not cause intestinal bleeding, tissue destruction, cancer, or shortening of life expectancy. IBS is classified as a benign functional disorder, meaning it alters gut function but does not damage the digestive organs themselves [3].

From a first person experience, many patients worry that persistent pain or bowel changes signal something dangerous. From a second person perspective, it is important for you to understand that IBS does not progress into inflammatory bowel disease, colon cancer, or other structural gastrointestinal conditions. This reassurance is supported by long term clinical observation and large population studies [10].

Why IBS Still Feels Serious to Patients

Although IBS is not life threatening, it can feel serious and overwhelming. From a third person clinical standpoint, IBS significantly affects quality of life, daily functioning, work productivity, social interactions, and emotional wellbeing [3].

From a first person perspective, patients often describe planning their day around bowel habits, avoiding travel or social events, and experiencing constant anxiety about symptom flare ups. From a second person viewpoint, if you are living with IBS, these disruptions are real and valid. The absence of visible disease does not reduce the burden of living with chronic, unpredictable symptoms.

Long Term Outlook of IBS

IBS is typically a chronic condition with a fluctuating course. From a third person medical perspective, symptoms may persist for years, improve gradually, or wax and wane depending on stress, diet, hormonal changes, and lifestyle factors [10].

From a first person experience, patients may notice periods of relative stability followed by unexpected symptom recurrence. From a second person perspective, understanding that symptom fluctuation is part of the natural course of IBS helps reduce fear when symptoms temporarily worsen. IBS does not shorten lifespan, but it does require long term symptom management and self awareness.

When IBS Symptoms Should Not Be Ignored

While IBS itself is benign, certain symptoms are not typical of IBS and require further evaluation. From a third person clinical standpoint, unexplained weight loss, persistent fever, anemia, blood in stool, or diarrhea that occurs during sleep suggest alternative diagnoses [6].

From a first person perspective, patients may worry about missing a serious condition. From a second person viewpoint, knowing which symptoms fall outside the IBS pattern provides safety and clarity. Responsible IBS care includes ongoing awareness of these warning signs, even after a diagnosis has been established.

Treatment Overview for IBS

Goals of IBS Treatment

From a third person medical perspective, the primary goal of IBS treatment is to reduce symptom severity, improve daily functioning, and restore quality of life. Because IBS is a functional disorder rather than a structural disease, treatment focuses on regulating gut function, calming gut brain signaling, and minimizing symptom triggers rather than repairing tissue damage [12].

From a first person experience, many patients enter treatment hoping for a single medicine that will permanently stop symptoms. From a second person perspective, it is important for you to understand that IBS management usually requires a combination of strategies rather than one isolated intervention. Setting realistic goals early prevents frustration and improves long term outcomes.

To explore a comprehensive treatment approach that includes diagnosis, diet, lifestyle guidance, herbs, and personalized care plans, refer to the pillar article on IBS Ayurvedic Treatment, Diagnosis, Symptoms and Cure, which offers an in-depth roadmap for holistic healing and patient empowerment.

Conventional Medical Approach

Conventional treatment for IBS is largely symptom directed. From a third person clinical standpoint, medications may be used to target specific complaints such as constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, or bowel urgency. These treatments aim to reduce symptom intensity rather than correct the underlying functional imbalance [12].

From a first person perspective, patients often experience partial or temporary relief with medications. From a second person viewpoint, you may notice that symptoms improve for a time but return when treatment stops. This pattern reflects the fact that symptom suppression alone does not fully address altered gut brain communication or visceral sensitivity.

Role of Stress Management and Behavioral Support

Stress management plays a significant role in IBS care. From a third person medical perspective, psychological stress directly influences gut motility, pain perception, and immune signaling through the gut brain axis [4].

From a first person experience, patients frequently report symptom flares during emotionally demanding periods even when diet remains unchanged. From a second person perspective, learning stress regulation techniques such as structured relaxation, sleep optimization, or behavioral therapy can reduce symptom frequency and intensity by stabilizing nervous system responses.

Dietary and Lifestyle Based Strategies

Dietary modification is a cornerstone of IBS management. From a third person standpoint, adjusting meal composition, portion size, and timing can reduce intestinal distension and symptom provocation. Structured dietary approaches have demonstrated benefit in selected patients [11].

From a first person experience, patients often feel overwhelmed by conflicting dietary advice. From a second person perspective, gradual and individualized dietary changes are more effective than extreme restriction. Lifestyle factors such as regular physical activity, consistent sleep patterns, and mindful eating support gut regulation and symptom stability [13].

For readers seeking a full spectrum IBS care plan integrating classical wisdom, individualized diet protocols, and Ayurvedic therapies, the linked pillar article provides structured guidance beyond conventional approaches:https://panaceayur.com/ibs-ayurvedic-treatment-diagnosis-symptoms-cure/

Limitations of Symptom Only Treatment

While symptom based treatment can improve comfort, it has limitations. From a third person medical perspective, focusing exclusively on symptom suppression may leave underlying gut sensitivity and neural dysregulation unchanged [12].

From a first person viewpoint, patients may feel discouraged by recurring symptoms despite treatment adherence. From a second person perspective, recognizing these limitations encourages a broader approach that integrates diet, lifestyle, stress regulation, and individualized care rather than relying solely on medications.

Diet and Lifestyle Role in IBS

Why Diet Strongly Influences IBS Symptoms

From a third person medical perspective, diet plays a central role in how IBS symptoms are expressed on a daily basis. The digestive system of an individual with IBS reacts differently to normal foods due to altered gut motility, visceral sensitivity, and gut brain signaling. Foods that are well tolerated by others may provoke pain, bloating, or bowel urgency in IBS without causing inflammation or damage [11].

From a first person experience, many patients report that symptoms begin or worsen shortly after eating, even when meals appear healthy. From a second person perspective, you may notice that symptoms depend not only on what you eat but also on how much you eat, how fast you eat, and the timing of meals. This explains why rigid food lists often fail unless eating patterns and digestive load are also addressed.

Meal Timing, Portion Size, and Eating Behavior

Eating behavior is as important as food selection in IBS. From a third person clinical standpoint, large meals increase intestinal distension and stimulate exaggerated gut contractions in sensitive individuals. Irregular meal timing further disrupts digestive rhythm and bowel predictability [13].

From a first person perspective, patients often notice less discomfort when meals are smaller and spaced evenly throughout the day. From a second person viewpoint, slowing down while eating, chewing thoroughly, and avoiding late night meals can reduce post meal pain and bloating. These adjustments support more stable gut signaling without requiring extreme dietary restriction.

Role of Fermentable Foods and Digestive Load

Certain carbohydrates are more likely to ferment in the intestine and produce gas. From a third person medical perspective, increased fermentation leads to intestinal distension, which triggers pain and bloating in IBS due to heightened sensory perception rather than excess gas production alone [11].

From a first person experience, patients may feel that many unrelated foods cause symptoms. From a second person perspective, understanding that the total digestive load matters more than one specific food can reduce anxiety around eating. Gradual dietary modification rather than aggressive elimination supports long term symptom stability.

Lifestyle Factors That Modify IBS Severity

Lifestyle habits strongly influence IBS symptoms through nervous system regulation. From a third person standpoint, poor sleep, physical inactivity, and chronic stress amplify gut sensitivity and disrupt bowel rhythm [4].

From a first person experience, patients often report symptom improvement during periods of better sleep or reduced stress. From a second person perspective, consistent sleep schedules, moderate physical activity, and daily stress management practices can significantly reduce symptom frequency and intensity without medication escalation.

Why Diet Alone Is Not a Complete Solution

While diet modification is essential, it is not sufficient as a standalone solution for most patients. From a third person medical perspective, focusing only on food ignores the underlying neural and functional dysregulation driving IBS symptoms [12].

From a first person viewpoint, patients may feel frustrated when strict diets fail to provide lasting relief. From a second person perspective, combining dietary awareness with lifestyle regulation and individualized care provides a more sustainable path toward long term symptom control.

For readers seeking a structured and personalized approach that integrates diet, lifestyle, diagnosis, and long term healing strategies, the complete framework is detailed in the IBS pillar guide: https://panaceayur.com/ibs-ayurvedic-treatment-diagnosis-symptoms-cure/

FAQs(Frequently Asked Question)

What exactly is IBS

IBS, or Irritable Bowel Syndrome, is a functional digestive condition that affects how the gut works rather than its structure. It leads to symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel habits even though medical tests usually appear normal.

Can IBS be cured permanently

IBS does not have a single universal cure using standard medical treatment, but long term improvement and sustained symptom control are possible. Many people experience significant relief when diet, lifestyle, stress regulation, and gut function are addressed together in a personalized way.

Does IBS last for life

IBS is often a long term condition, but symptoms do not remain constant. Many people experience periods of improvement or remission, especially when triggers are identified and managed properly. IBS does not necessarily worsen over time.

Is IBS caused only by stress

Stress alone does not cause IBS, but it can strongly worsen symptoms. Emotional stress affects gut movement and pain perception through the gut brain connection, which explains why symptoms often flare during stressful periods.

Is IBS more common in women than men

IBS is reported more frequently in women than in men. Hormonal factors, pain sensitivity, and differences in gut nervous system responses may contribute to this variation.

Is IBS dangerous

IBS is not a life threatening condition and does not cause cancer or permanent damage to the intestines. However, it can significantly affect daily life and wellbeing if not managed properly.

When should IBS symptoms be checked by a doctor

Symptoms such as unexplained weight loss, persistent fever, blood in the stool, anemia, or bowel symptoms that wake a person from sleep are not typical of IBS and should be evaluated by a doctor.

REFERENCE LIST

[1] Drossman, D. A., Hasler, W. L. (2016). Rome IV—Functional GI disorders: Disorders of gut–brain interaction. Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1257–1261.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035

[2] Canavan, C., West, J., Card, T. (2014). The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical Epidemiology, 6, 71–80.

https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S40245

[3] Gralnek, I. M., Hays, R. D., Kilbourne, A., Naliboff, B., Mayer, E. A. (2000). The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology, 119(3), 654–660.

https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2000.16484

[4] Mayer, E. A., Savidge, T., Shulman, R. J. (2014). Brain–gut microbiome interactions and functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology, 146(6), 1500–1512.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.037

[5] Ford, A. C., Lacy, B. E., Talley, N. J. (2017). Irritable bowel syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine, 376, 2566–2578.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1607547

[6] Lacy, B. E., Mearin, F., Chang, L., Chey, W. D., Lembo, A. J., Simren, M., Spiller, R. (2016). Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1393–1407.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031

[7] Camilleri, M. (2021). Visceral hypersensitivity and IBS. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 18, 51–66.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-00349-0

[8] Simrén, M., Barbara, G., Flint, H. J., Spiegel, B. M. R., Spiller, R. C., Vanner, S., Verdu, E. F., Whorwell, P. J., Zoetendal, E. G. (2013). Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders. Gut, 62(1), 159–176.

https://gut.bmj.com/content/62/1/159

[9] Longstreth, G. F., Thompson, W. G., Chey, W. D., Houghton, L. A., Mearin, F., Spiller, R. C. (2006). Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology, 130(5), 1480–1491.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061

[10] Ford, A. C., Moayyedi, P., Lacy, B. E., Lembo, A. J., Saito, Y. A., Schiller, L., Soffer, E., Spiegel, B. M., Quigley, E. M. M. (2014). American College of Gastroenterology monograph on IBS. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 109(S1), S2–S26.

https://journals.lww.com/ajg/fulltext/2014/08001

[11] Varjú, P., Farkas, N., Hegyi, P., Garami, A., Szabó, I., Illés, A., Solymár, M. (2017). Low FODMAP diet improves IBS symptoms. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 23(28), 5240–5248.

https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i28.5240

[12] Chey, W. D., Kurlander, J., Eswaran, S. (2015). Irritable bowel syndrome: A clinical review. JAMA, 313(9), 949–958.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2108892

[13] McKenzie, Y. A., Bowyer, R. K., Leach, H., Gulia, P., Horobin, J., O’Sullivan, N. A., Pettitt, C., Reeves, L. B., Seamark, L., Williams, M., Thompson, J., Lomer, M. C. E. (2016). British Dietetic Association IBS guidelines. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 29(5), 549–575.