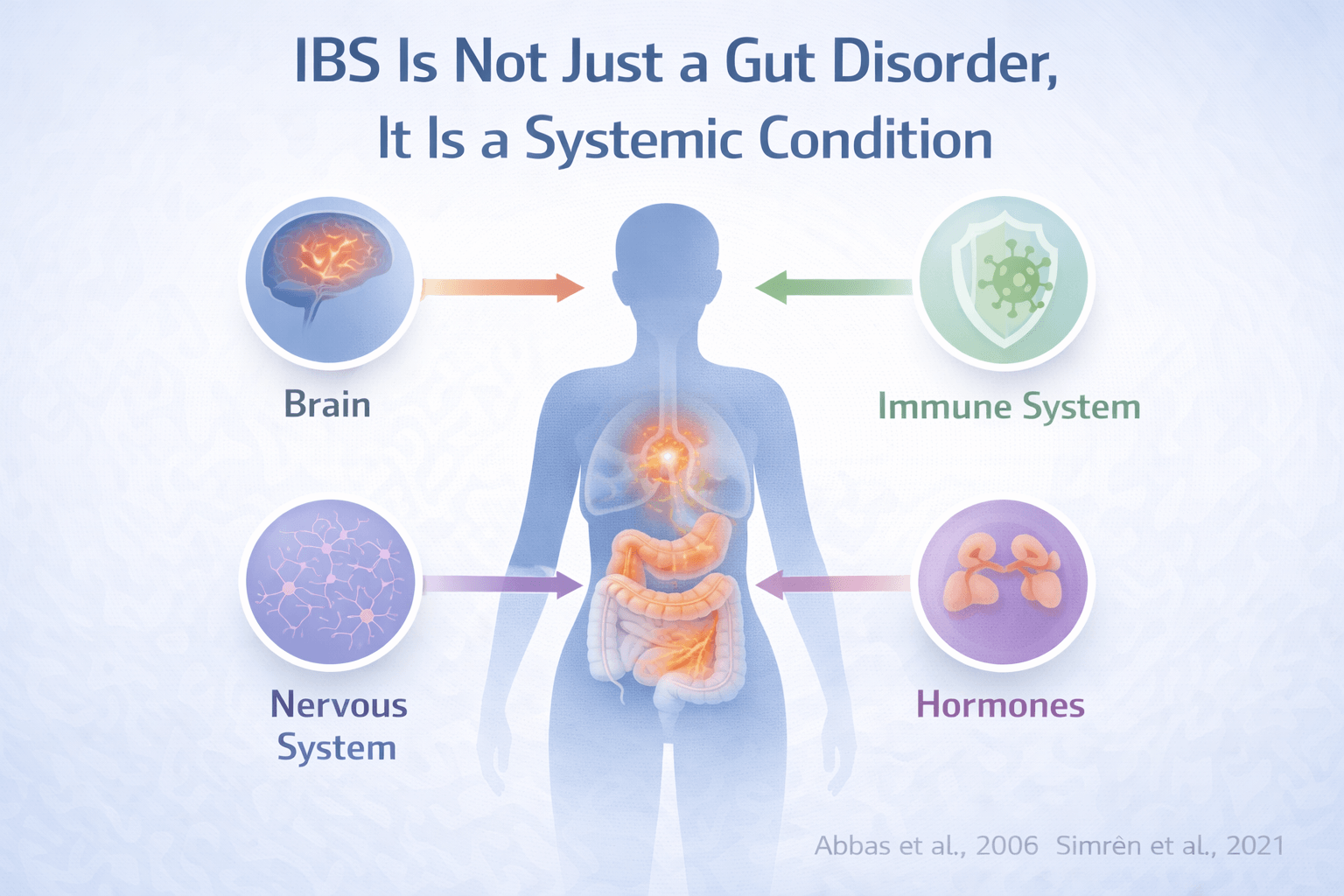

- IBS Is Not Just a Gut Disorder, It Is a Systemic Condition

- Gut Brain Axis Dysfunction Beyond Simple Stress

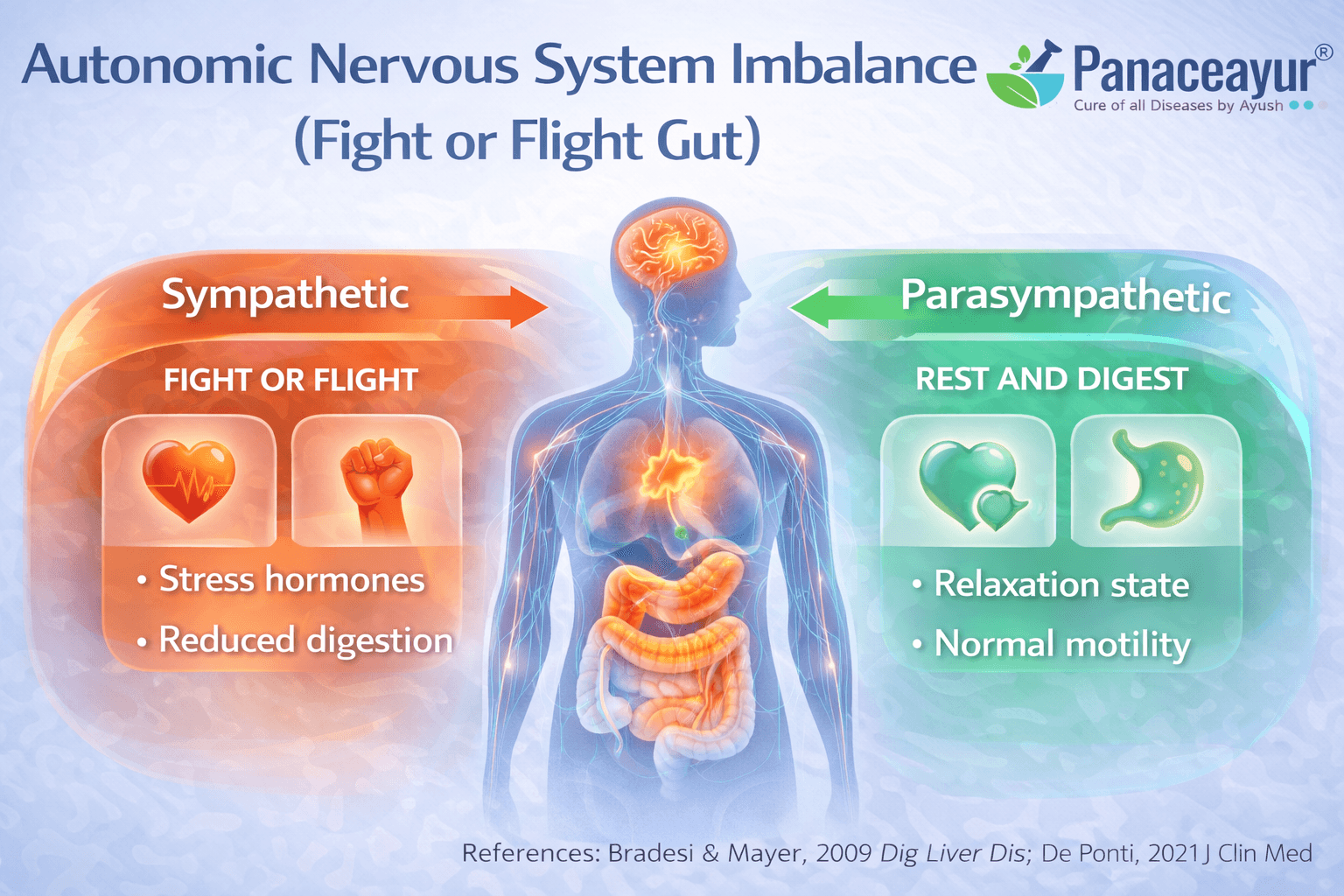

- Autonomic Nervous System Imbalance (Fight or Flight Gut)

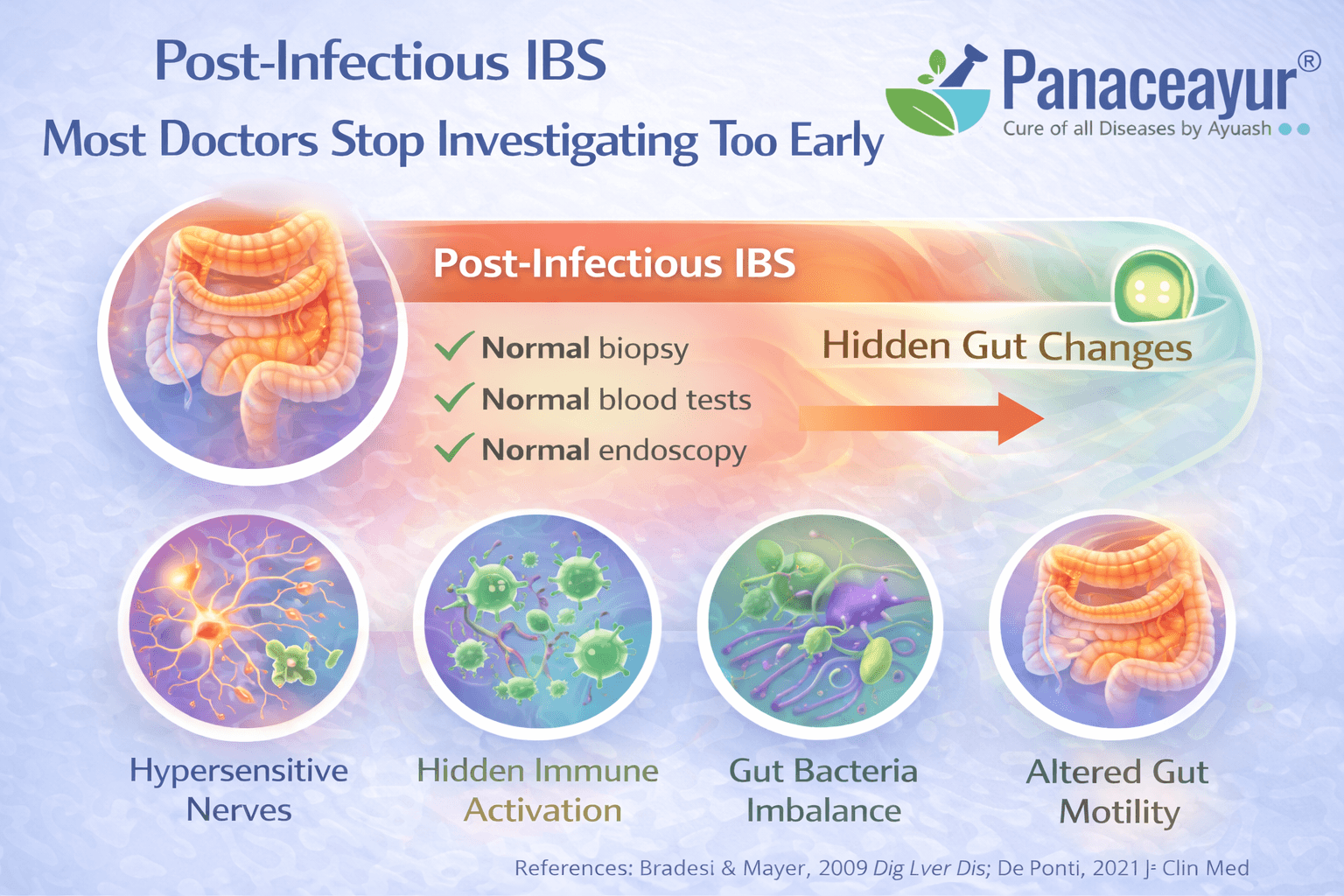

- Post Infectious IBS Most Doctors Stop Investigating Too Early

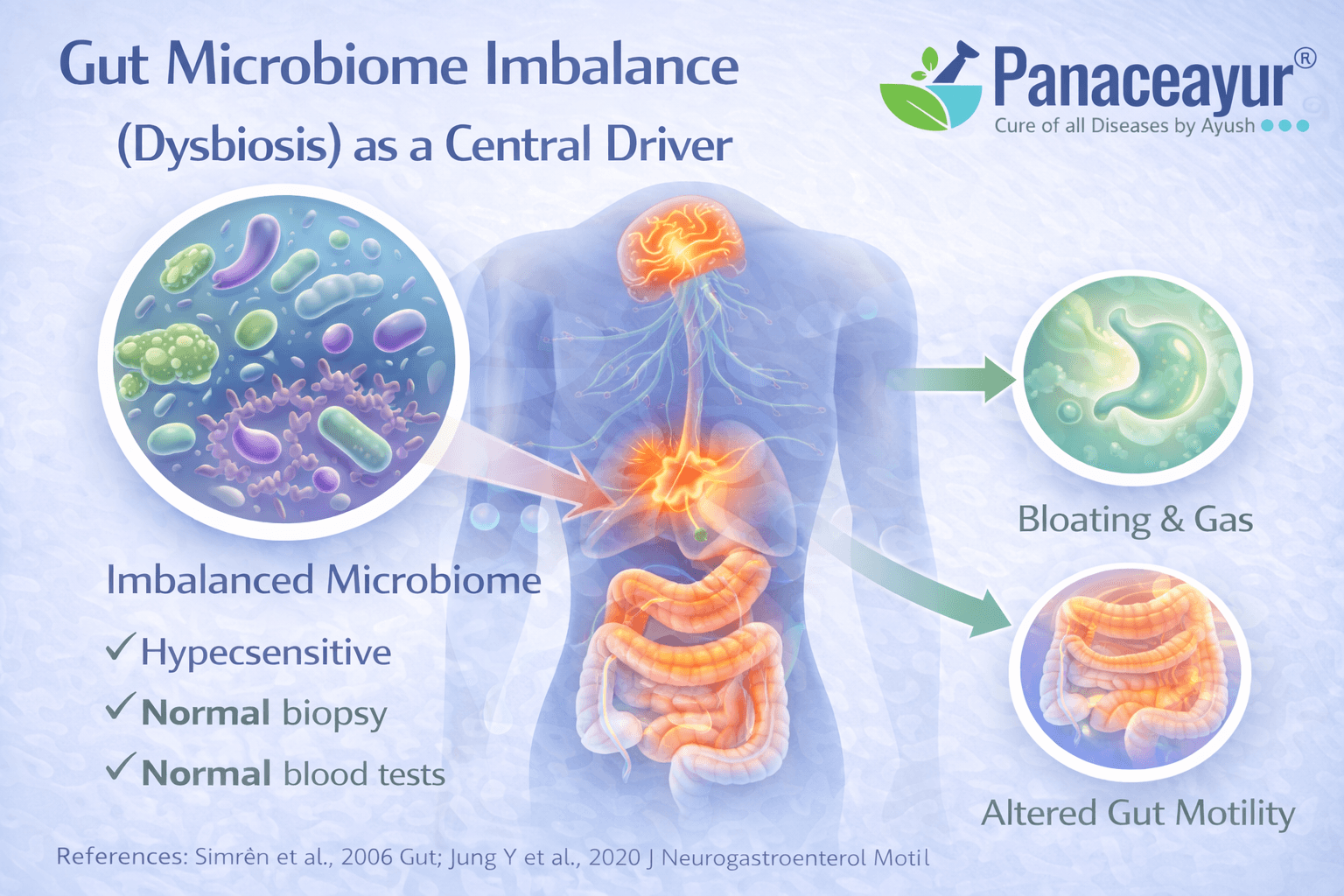

- Gut Microbiome Imbalance (Dysbiosis) as a Central Driver

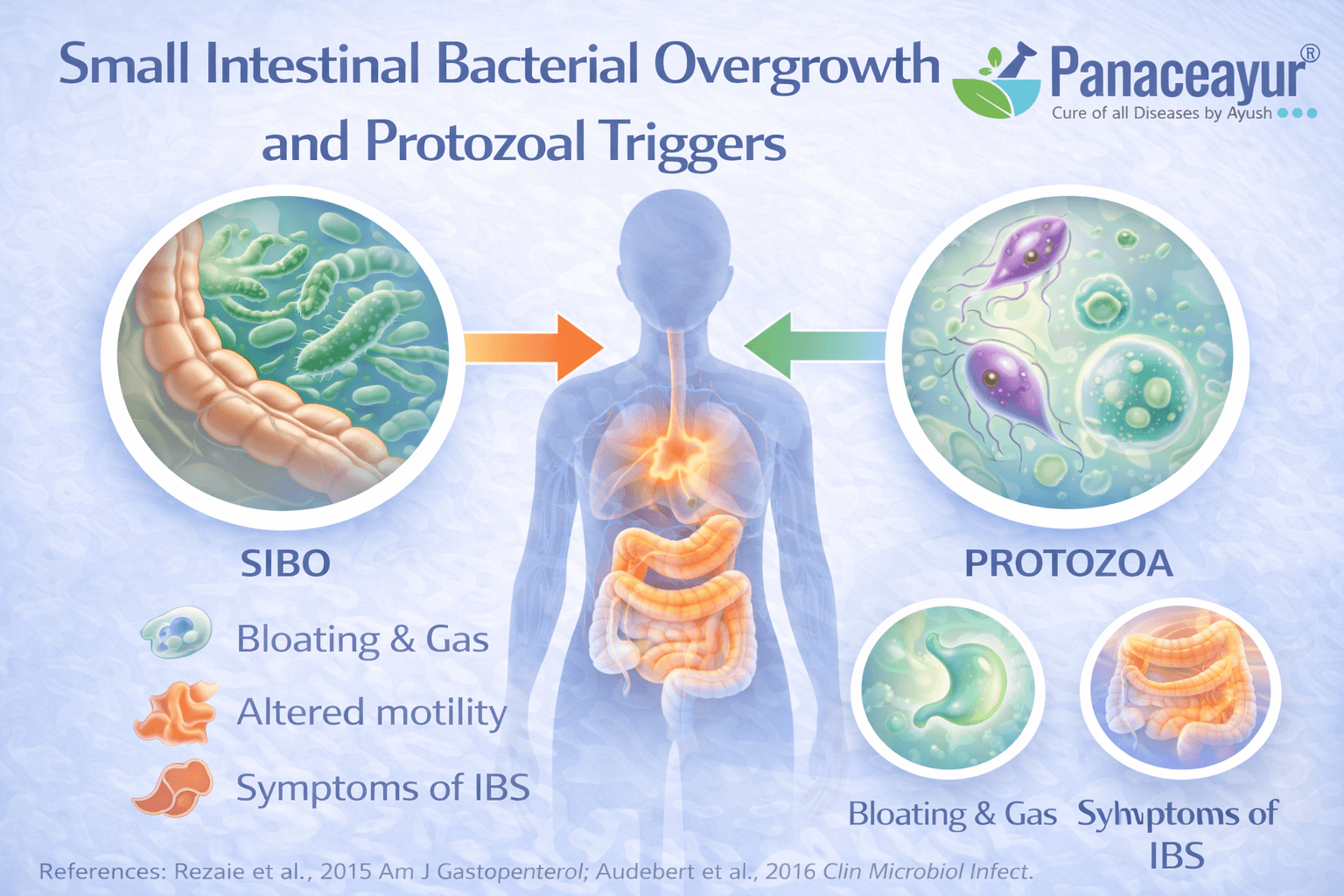

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Protozoal Triggers

- Gut Barrier Dysfunction Without Using Buzzwords

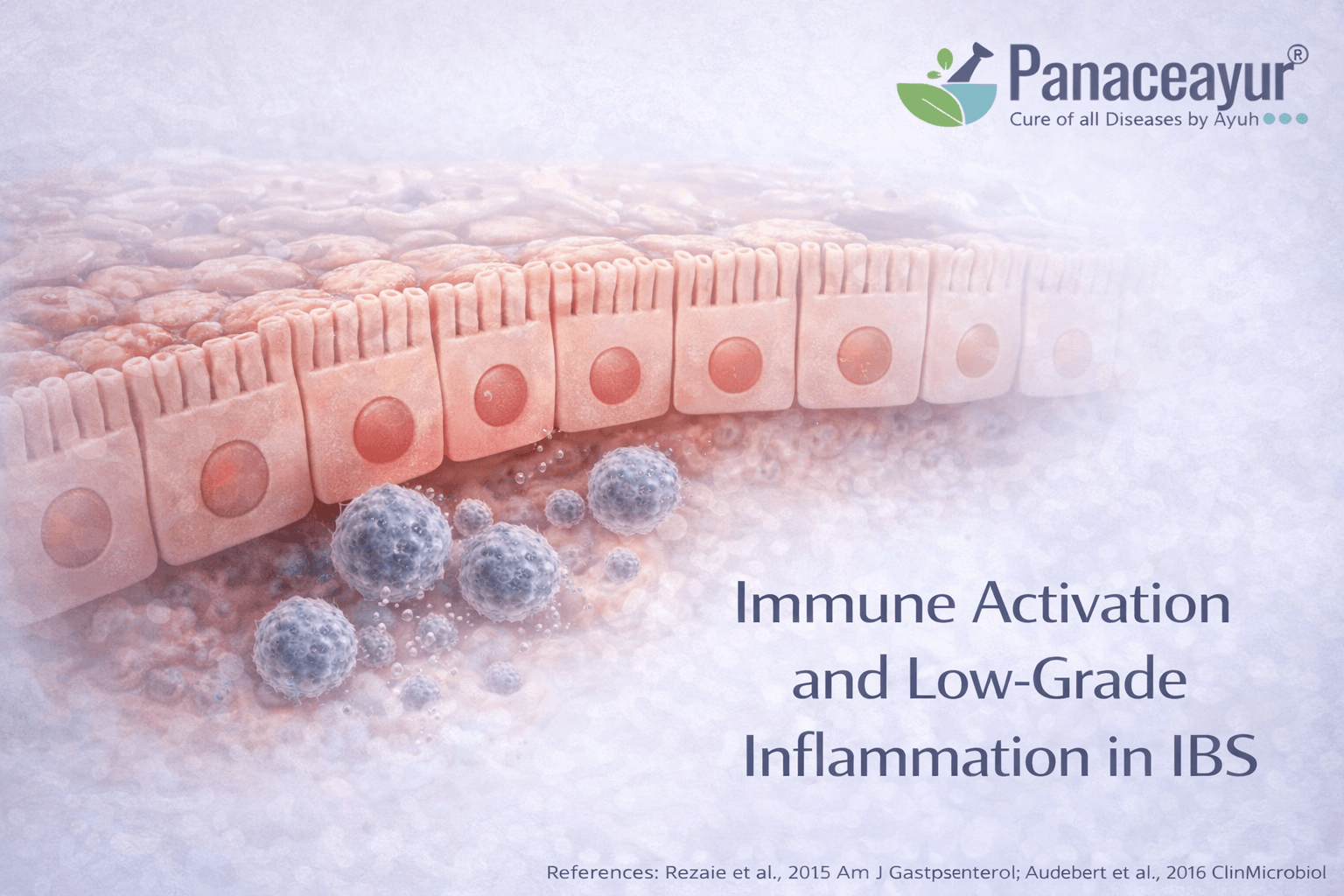

- Immune Activation and Low Grade Inflammation

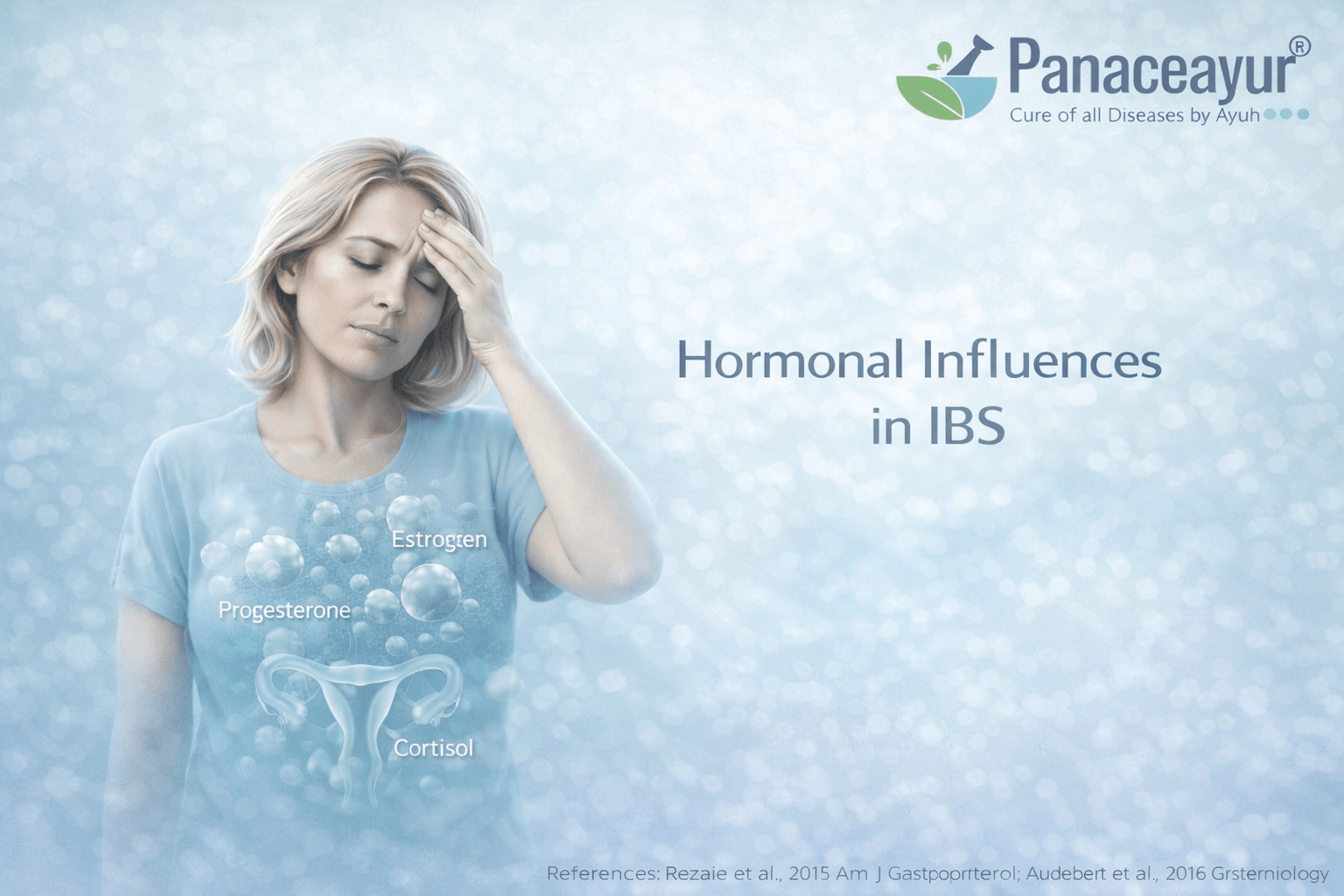

- Hormonal Influences Doctors Rarely Map Properly

- Sleep, Circadian Rhythm, and Digestive Timing

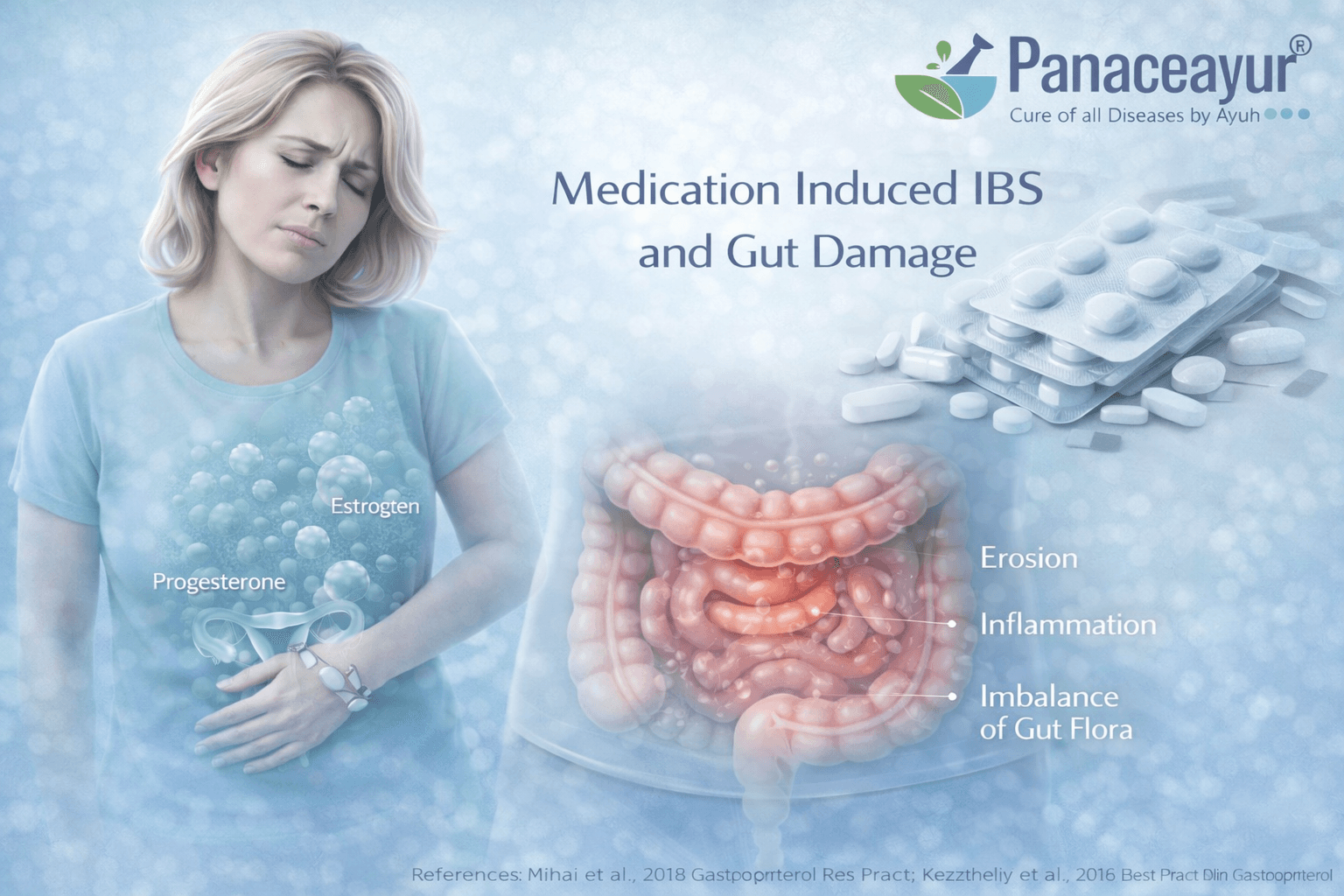

- Medication Induced IBS and Gut Damage

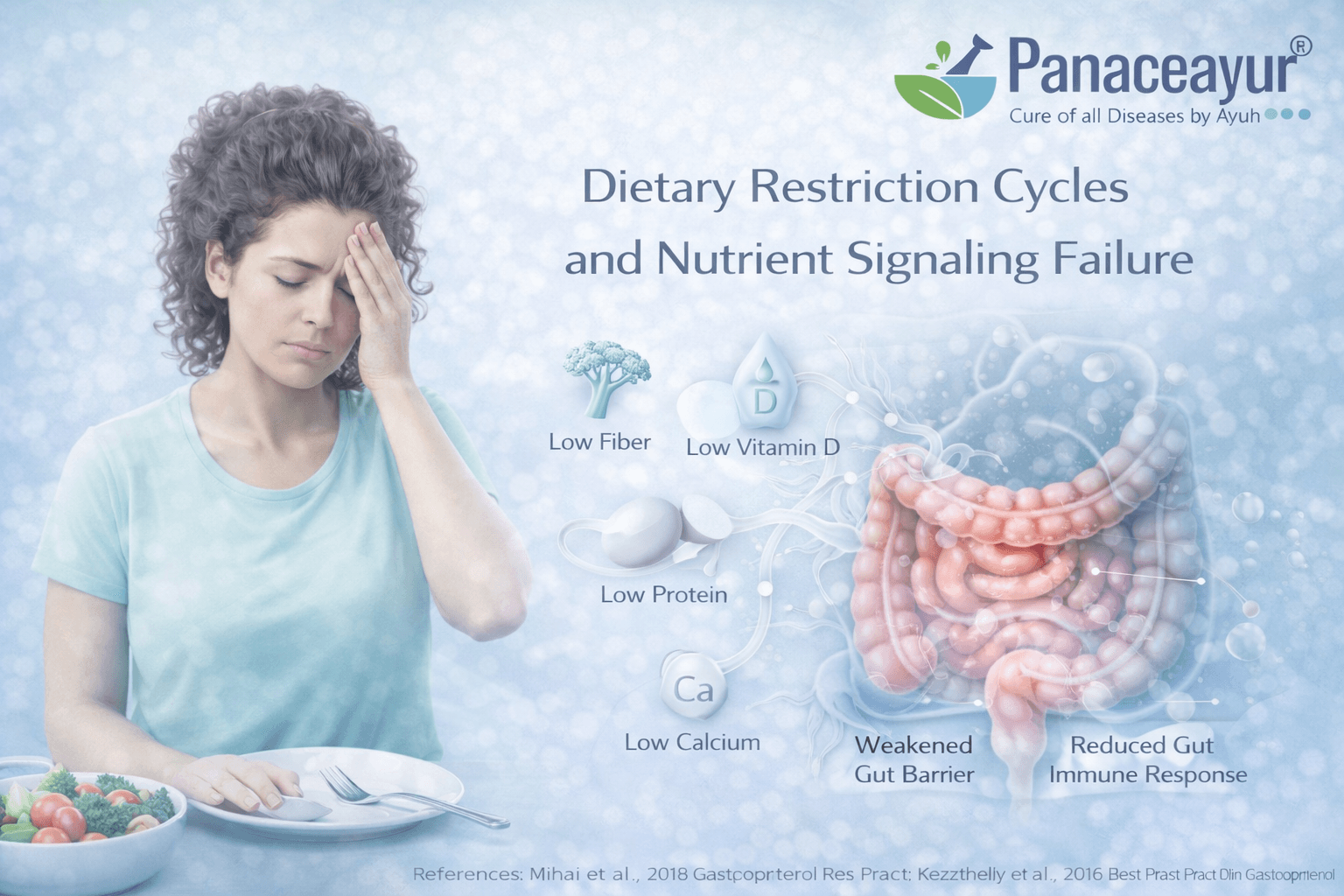

- Dietary Restriction Cycles and Nutrient Signaling Failure

- Emotional Suppression and Trauma Physiology

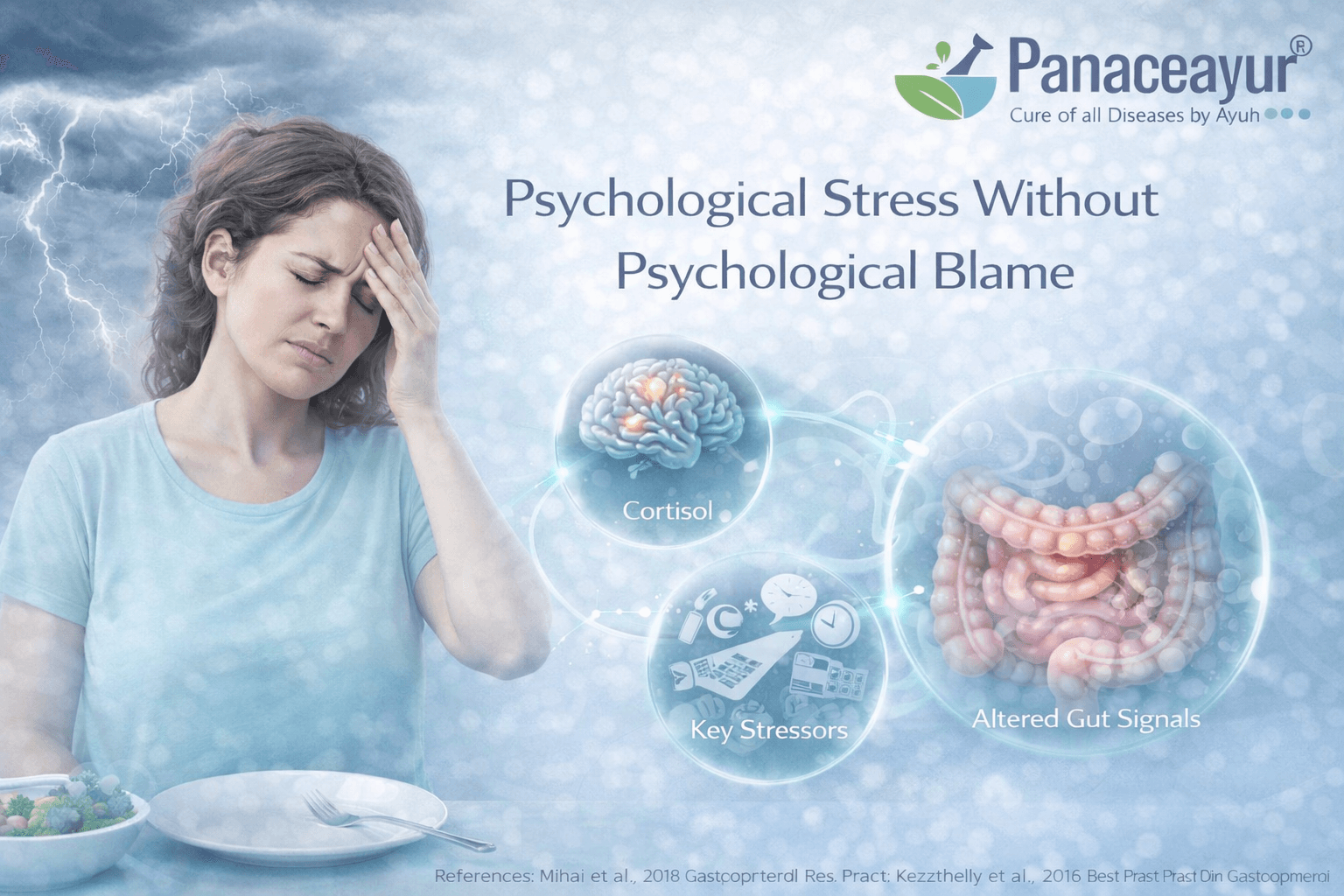

- Psychological Stress Without Psychological Blame

- Why Treating IBS as One Disease Always Fails and Where to Look for a Complete Cure

- Why Standard IBS Tests Miss These Causes

- IBS Overlap With Other Chronic Conditions

- Prognosis, Reversibility, and Recovery Factors

- When to Stop Symptom Management and Look for Root Cause Healing

- Key Takeaway for Patients and Clinicians

- FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- Reference

Hidden Triggers Behind Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Why IBS Persists Despite Normal Tests

IBS is still misunderstood as a functional condition

Irritable bowel syndrome is commonly labeled as a functional disorder, a term that suggests symptoms occur without a clear biological explanation. When doctors use this label, they often mean that no structural damage is visible on routine testing. From the patient’s perspective, this creates confusion and frustration because the pain, bloating, bowel changes, and fatigue are very real and disruptive. As defined under the Rome IV framework, IBS is classified as a disorder of gut brain interaction, not a disease that produces obvious lesions or inflammation. This classification has unintentionally led many clinicians to underestimate the depth of physiological dysfunction involved and to reassure patients prematurely that nothing serious is wrong [2].

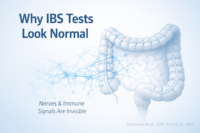

Why standard medical tests usually appear normal

In most cases, you are sent for investigations such as colonoscopy, ultrasound, blood tests, or basic stool analysis. These tools are designed to detect conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, infections, or bleeding. In IBS, these tests are expected to be normal because the core problem lies in altered nerve signaling, immune activity, gut permeability, and microbiome imbalance rather than visible tissue damage. When reports come back normal, doctors often conclude that there is no ongoing disease process, even though the person sitting in front of them continues to suffer daily symptoms [17].

How this gap affects patients and long term outcomes

For the patient, normal test results can feel invalidating. You may begin to question your own symptoms or feel that the problem is being blamed on stress or anxiety alone. From the clinician’s side, treatment often shifts toward symptom suppression rather than deeper evaluation. From a broader medical perspective, this gap between normal investigations and persistent symptoms is one of the main reasons IBS remains chronic for many people. Until both doctors and patients understand why conventional tests fail to capture the true biology of IBS, the condition will continue to be misunderstood, undertreated, and unnecessarily prolonged [2] [17].

IBS Is Not Just a Gut Disorder, It Is a Systemic Condition

IBS involves the gut, brain, and immune system together

Irritable bowel syndrome has long been described as a digestive problem, but modern research shows that this view is incomplete. IBS is now understood as a condition involving continuous interaction between the gut, the brain, and the immune system. When you experience IBS symptoms, the issue is not limited to the intestines alone. Signals between the brain and the gut become dysregulated, and immune activity within the gut lining further amplifies this imbalance. From a clinical standpoint, this explains why pain, bloating, urgency, or constipation can occur even when there is no visible damage in the digestive tract [1] [2].

Why focusing only on digestion leads to treatment failure

When doctors focus only on bowel movements or diet, they often miss the broader physiological picture. IBS symptoms are influenced by nerve sensitivity, stress response systems, immune mediators, and altered communication between the central nervous system and the digestive tract. As a patient, you may notice that symptoms worsen during emotional stress, sleep disruption, illness, or hormonal changes. From the doctor’s perspective, treating IBS as a gut-only disorder limits outcomes because the underlying regulatory systems remain unaddressed [1] [2].

IBS commonly affects multiple systems beyond the intestine

Many people with IBS report symptoms that extend well beyond the digestive system. These may include fatigue, headaches, poor sleep, anxiety, low mood, pelvic discomfort, or widespread body pain. Clinically, IBS frequently overlaps with other functional and chronic conditions such as migraine, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue states. This multi-system symptom pattern indicates that IBS reflects a broader disturbance in how the body regulates sensation, immunity, and stress, rather than an isolated intestinal disease [15].

How this systemic view changes understanding and care

When IBS is recognized as a systemic condition, both patients and clinicians gain clarity. You no longer need to wonder why symptoms feel widespread or unpredictable. Doctors can better understand why standard gut-focused treatments alone often provide incomplete relief. Viewing IBS through a gut brain immune lens allows for a more accurate explanation of symptoms and opens the door to deeper, mechanism-based approaches rather than repeated symptom suppression [1] [2] [15].

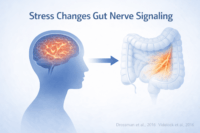

Gut Brain Axis Dysfunction Beyond Simple Stress

Gut brain signaling is biologically disrupted in IBS

In irritable bowel syndrome, communication between the brain and the digestive tract becomes dysregulated at a physiological level. This is not a vague concept or a psychological explanation. Research shows that neural signaling pathways connecting the central nervous system and the gut function abnormally in IBS. As a result, the intestine may contract too quickly or too slowly, pain signals may be amplified, and normal digestive sensations may be interpreted as distressing. When you feel pain or urgency without visible disease, it reflects altered gut brain signaling rather than imagination or weakness [1].

How Rome IV reframed IBS as a gut brain interaction disorder

The Rome IV framework formally reclassified IBS as a disorder of gut brain interaction. This shift was critical because it acknowledged that symptoms arise from dysfunctional communication rather than structural damage. From a clinical standpoint, this explains why colonoscopy and imaging are usually normal. From the patient’s perspective, it clarifies why symptoms feel real and persistent despite reassuring test results. Doctors who follow this model understand that IBS is rooted in regulatory failure between the nervous system and the gut, not in isolated bowel pathology [2].

Stress physiology affects the gut even without emotional distress

Stress in IBS should not be confused with emotional weakness or anxiety alone. Stress physiology refers to how the body responds to perceived threat through hormones and autonomic nervous system activity. Even when a person feels emotionally stable, chronic activation of stress pathways can alter gut motility, secretion, immune signaling, and pain perception. You may notice symptom flares during work pressure, sleep loss, illness, or long term strain, even if you do not feel consciously anxious. This reflects biological stress signaling acting on the gut, not a purely psychological cause [11].

Visceral hypersensitivity explains pain without damage

One of the defining features of IBS is visceral hypersensitivity. This means that the nerves supplying the gut become overly responsive. Sensations that are normally painless, such as gas movement or mild distension, may be experienced as significant pain or discomfort. From the doctor’s viewpoint, this explains why physical findings are absent while symptoms are severe. From the patient’s experience, it explains why pain feels disproportionate to what tests show. Visceral hypersensitivity is a measurable neurophysiological phenomenon and a central component of IBS pathophysiology [14].

Why this is more than telling patients to relax

When gut brain axis dysfunction is misunderstood as simple stress, patients are often advised to relax, meditate, or worry less. While stress regulation can help, it does not address the core signaling abnormalities driving IBS. A deeper understanding of gut brain dysfunction allows clinicians to recognize IBS as a real neurogastroenterological condition. For patients, this perspective removes blame and validates symptoms, while pointing toward approaches that target regulation and sensitivity rather than dismissing the condition as stress related [1] [2] [11] [14].

Autonomic Nervous System Imbalance (Fight or Flight Gut)

The autonomic nervous system plays a central role in IBS symptoms

In irritable bowel syndrome, the autonomic nervous system often remains in an imbalanced state. This system controls involuntary functions such as digestion, bowel movement, blood flow, and pain modulation. Research shows that many IBS patients exhibit autonomic imbalance, where the sympathetic system linked to the fight or flight response dominates over the parasympathetic system responsible for rest and digestion. From a clinical perspective, this imbalance helps explain why symptoms fluctuate unpredictably and worsen during stress, illness, or fatigue even when no structural disease is present [3].

Reduced vagal tone disrupts normal gut motility

The vagus nerve is a key component of the parasympathetic nervous system and plays a major role in regulating gut movement, secretion, and coordination. In IBS, vagal tone is often reduced, meaning the calming signals that support normal digestion are weakened. When this happens, bowel contractions may become irregular, leading to diarrhea, constipation, or alternating patterns. As a patient, you may notice that digestion feels uncoordinated or overly sensitive, especially during periods of mental or physical strain. From a physiological standpoint, reduced vagal activity removes an important stabilizing influence on the gut [1].

How nervous system imbalance amplifies pain signals

Autonomic imbalance does not only affect motility. It also alters how pain signals from the gut are processed. When sympathetic activity remains dominant, sensory nerves in the intestine become more reactive. Normal digestive sensations such as gas movement or bowel distension can be interpreted by the brain as pain or urgency. This phenomenon contributes directly to pain amplification in IBS and explains why symptoms can feel severe despite minimal physical triggers. For clinicians, this reinforces that IBS pain is neurologically mediated rather than imaginary or exaggerated [14].

Why this mechanism is often overlooked in routine care

In everyday practice, autonomic function is rarely assessed during gastrointestinal evaluation. Tests focus on structure and inflammation rather than nervous system regulation. As a result, patients are often told that stress alone is responsible, without explaining the biological pathways involved. Understanding autonomic imbalance shifts the conversation from blame to mechanism. It allows doctors to recognize IBS as a disorder of regulation and signaling, and it helps patients understand why symptoms worsen during pressure, poor sleep, or emotional suppression even in the absence of visible disease [1] [3] [14].

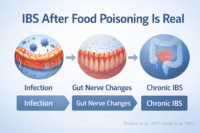

Post Infectious IBS Most Doctors Stop Investigating Too Early

How an acute gut infection can permanently alter bowel function

Many people with irritable bowel syndrome can trace the beginning of their symptoms to a clear infectious event. This may include food poisoning, traveler’s diarrhea, viral gastroenteritis, or a severe stomach infection that appeared to resolve at the time. From a medical standpoint, this form is recognized as post infectious IBS. Research shows that a significant proportion of patients develop chronic IBS symptoms after an acute gastrointestinal infection, even when the original pathogen is no longer detectable [4]. As a patient, you may clearly remember that your digestion never returned to its previous baseline after that illness.

What changes persist after the infection clears

Although visible symptoms of infection may disappear, long lasting biological changes often remain. These include persistent low grade immune activation, altered gut nerve sensitivity, disruption of gut brain signaling, subtle impairment of the intestinal barrier, and long term shifts in gut microbiota. From the clinician’s perspective, these changes rarely show up on routine investigations, which is why the infection is often considered fully resolved once stool tests and basic labs normalize. For the person experiencing IBS, however, the gut continues to behave differently, leading to ongoing bloating, pain, urgency, or altered bowel habits [4].

Why investigation commonly stops at the clinical ground level

In routine clinical practice, the immediate goal is to treat the acute infection and rule out dangerous conditions. Once diarrhea, fever, or vomiting resolve, both doctor and patient often feel a sense of closure. Many patients are understandably not ready to pursue further investigations when symptoms appear to have settled. You may feel relieved, fatigued by testing, or reassured by normal reports, and prefer to move on rather than continue medical evaluation.

At the same time, doctors may consciously or unconsciously avoid pushing further testing when a patient appears stable. There is often a desire to reassure, to avoid unnecessary procedures, and to remain in the good books of the patient when no alarm signs are present. In busy clinical settings, time pressure and high patient load further reduce the opportunity to explore subtle post infectious consequences that require detailed history and follow up.

Another important factor is awareness. Not all clinicians are fully trained to recognize post infectious IBS as a long term biological condition. Some doctors still view infections as isolated, self-limited events rather than triggers that can permanently alter gut regulation. When symptoms later reappear, the connection to the original infection is frequently overlooked rather than deliberately ignored.

Why research systems also contribute to early abandonment

At the researcher level, post infectious IBS occupies an uncomfortable space. It does not produce visible inflammation, structural damage, or clear biomarkers. This makes it less attractive for large-scale funding compared to conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease or cancer. As a result, fewer long term studies are designed specifically to follow patients after infection for extended periods.

In addition, post infectious IBS involves multiple overlapping mechanisms including immune activation, nervous system sensitization, microbiome disruption, and altered gut brain communication. This complexity makes it difficult to study using single-variable research models. Researchers often prioritize symptom classification and treatment trials over investigating upstream triggers such as infection because the latter are harder to measure and standardize.

There is also limited commercial incentive. Post infectious IBS does not point toward a single drug target, which reduces pharmaceutical driven research interest. Many studies therefore focus on managing established IBS symptoms rather than understanding how an infection initiates long term dysfunction in the first place.

Delayed symptom emergence further complicates research. In many patients, IBS symptoms develop weeks or months after the infection. Short follow up periods in clinical studies may miss this transition entirely, leading to underrecognition of post infectious IBS in the scientific literature.

Long term outlook after post infectious IBS develops

The prognosis of post infectious IBS varies widely. Some individuals improve gradually, while others experience persistent or relapsing symptoms for years. Long term studies show that IBS symptoms can remain stable or fluctuate long after the initial infection, particularly when underlying gut brain and immune changes are not addressed early [16]. From the patient’s perspective, this explains why reassurance alone does not lead to recovery. From the clinician’s perspective, it highlights why early recognition and sustained evaluation matter.

Why early recognition changes outcomes

When post infectious IBS is identified early, both patients and doctors gain clarity. You no longer need to question why symptoms appeared suddenly after an illness that seemed to resolve. Doctors can better understand that the infection acted as a biological trigger rather than a psychological one. Acknowledging this mechanism helps prevent missed opportunities, reduces repeated normal testing, and avoids years of ineffective symptom based management [4] [16].

Gut Microbiome Imbalance (Dysbiosis) as a Central Driver

How altered gut microbiota shapes IBS symptoms

In irritable bowel syndrome, the gut microbiome is frequently altered in both composition and function compared to healthy individuals. This dysbiosis includes reduced microbial diversity, depletion of beneficial species, and relative overgrowth of less favorable organisms. These changes influence fermentation patterns, gas production, bile acid metabolism, and gut motility. From your perspective as a patient, this may feel like bloating, discomfort, or unpredictable bowel habits that do not clearly correlate with what you eat. From a biological standpoint, altered gut microbiota provides a core explanation for why IBS symptoms persist even when structural tests appear normal [5].

Why dysbiosis often develops in the first place

Microbiome imbalance in IBS rarely arises spontaneously. It is often shaped by earlier events such as gastrointestinal infections, repeated antibiotic exposure, chronic stress, poor sleep, restrictive diets, or long term use of acid suppressing medications. Each of these factors can subtly but persistently alter microbial balance. From a clinical angle, this explains why IBS often follows a clear trigger rather than developing without context. From the patient’s experience, it clarifies why symptoms may begin after illness, medication use, or lifestyle disruption rather than dietary change alone [5].

Microbiome and immune system interaction in IBS

The gut microbiome is in constant communication with the immune system lining the intestine. When microbial balance is disrupted, immune cells may remain in a state of low grade activation. This does not cause the overt inflammation seen in inflammatory bowel disease, but it is sufficient to alter nerve signaling and gut sensitivity. For clinicians, this explains why immune driven symptoms can exist without abnormal blood markers. For patients, it explains fluctuating pain, urgency, and sensitivity to foods that were previously well tolerated [6].

How dysbiosis contributes to barrier dysfunction

A healthy microbiome supports the intestinal barrier, which regulates what passes from the gut into the body. In IBS, dysbiosis can weaken this barrier, increasing permeability and allowing microbial byproducts to interact more directly with immune and nerve cells. This does not necessarily cause visible inflammation, but it amplifies gut reactivity and symptom variability. From your perspective, this may feel like sudden intolerance to foods or worsening symptoms during stress. Clinically, barrier dysfunction explains why IBS remains active despite normal imaging and routine laboratory findings [8].

Why dysbiosis is frequently missed at the ground level

In everyday practice, microbiome imbalance is rarely investigated beyond ruling out infections. Standard stool tests are designed to detect pathogens, not functional imbalance or loss of microbial diversity. As a result, doctors may conclude that the gut microbiome is normal simply because no infection is detected. Patients may also hesitate to pursue further testing once serious disease is excluded, especially if symptoms fluctuate rather than remain constant. This combination of testing limitations and clinical reassurance allows dysbiosis to persist unaddressed [5].

Research level challenges that limit deeper recognition

At the research level, microbiome related IBS mechanisms face practical barriers. The microbiome is highly individual, dynamic, and influenced by diet, geography, medications, and lifestyle. This variability makes it difficult to establish standardized diagnostic thresholds. Many studies therefore focus on symptom outcomes rather than upstream microbial patterns. In addition, there is limited commercial incentive to deeply investigate dysbiosis because it does not point toward a single drug target. These factors slow translation of microbiome research into routine clinical practice [6].

Why addressing dysbiosis changes the IBS narrative

When dysbiosis is recognized as a central driver, IBS no longer appears as a vague or purely functional disorder. Instead, it becomes a condition rooted in altered microbial, immune, and barrier regulation. For patients, this understanding removes confusion about why symptoms persist despite normal tests. For clinicians, it provides a unifying framework that connects post infectious changes, immune activation, food sensitivity, and nervous system hypersensitivity. Addressing microbiome imbalance early helps prevent the cycle of repeated testing and symptom suppression that characterizes much of conventional IBS care [5] [6] [8].

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Protozoal Triggers

How microbial overgrowth alters normal digestion

In a healthy digestive system, most bacteria reside in the large intestine, while the small intestine contains relatively low bacterial counts. In some people with irritable bowel syndrome, this balance is disrupted. Bacteria that normally belong in the colon migrate or overgrow in the small intestine, leading to abnormal fermentation of food before it is fully digested. This microbial overgrowth changes gas production, bile acid handling, and nutrient absorption. From your perspective as a patient, this may present as bloating soon after meals, excessive gas, abdominal discomfort, or loose stools that seem disproportionate to what you eat. From a biological standpoint, these overgrowth patterns represent a functional shift in microbial location and behavior rather than a new infection [5].

Why SIBO can worsen or mimic IBS symptoms

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth can directly reproduce many classic IBS symptoms. Excess fermentation in the small intestine leads to gas expansion, intestinal distension, and altered motility. This distension stimulates gut nerves that are already sensitized in IBS, amplifying pain and urgency. Clinical studies have shown that reducing bacterial overgrowth in selected patients can lead to measurable improvement in IBS symptoms, supporting the role of SIBO as an important contributor rather than a coincidental finding [7]. For some individuals, SIBO acts as a primary driver, while for others it worsens an already dysregulated gut brain and microbiome environment.

Protozoal triggers as a frequently overlooked contributor

Beyond bacterial overgrowth, certain protozoal organisms can persist in the gut and contribute to IBS-like symptoms. These organisms may not cause acute infection or severe illness but can subtly interfere with digestion, immune signaling, and gut motility. From a patient’s experience, symptoms may fluctuate, partially improve, or relapse without clear explanation. From a clinical standpoint, protozoal involvement is often missed because routine stool tests may not detect low-level or intermittent shedding. This makes protozoal triggers an underrecognized but clinically relevant factor in chronic IBS presentations [5].

Diagnostic limitations that create confusion

Testing for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and protozoal triggers is far from straightforward. Breath tests used for SIBO have variable sensitivity and specificity, and results can be influenced by diet, transit time, and testing protocols. False positives and false negatives are common. Stool tests may appear normal even when functional overgrowth is present. As a result, doctors may dismiss SIBO or protozoal involvement entirely, or patients may receive conflicting opinions depending on where and how testing is performed. These diagnostic limitations contribute significantly to ongoing uncertainty in IBS management [17].

Ground level reasons SIBO and protozoa are often underinvestigated

At the clinical ground level, once serious disease is excluded, both patients and doctors may hesitate to pursue further testing for overgrowth. You may feel exhausted by repeated investigations or reluctant to undergo restrictive preparation diets and breath tests. Doctors, on the other hand, may be cautious because of inconsistent test reliability and lack of standardized treatment pathways. In busy practice settings, addressing SIBO or protozoal triggers requires time, follow up, and patient education, which are not always feasible.

Research level challenges that limit clarity

From a research perspective, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth remains controversial. There is no universally accepted diagnostic gold standard, and study designs vary widely. This has led to debate over how common SIBO truly is in IBS populations. In addition, overgrowth often overlaps with dysbiosis, motility disorders, and immune activation, making it difficult to isolate as a single cause. Because outcomes are multifactorial and individualized, large scale trials struggle to produce simple conclusions, slowing translation into routine guidelines [7] [17].

Why microbial overgrowth matters in the broader IBS picture

When viewed in isolation, SIBO and protozoal triggers can seem confusing or inconsistent. When viewed within the broader IBS framework, they fit logically as contributors that interact with microbiome imbalance, impaired motility, immune activation, and visceral hypersensitivity. For patients, this explains why treatments may work temporarily and then fail, or why symptoms recur after partial improvement. For clinicians, it reinforces that microbial overgrowth is not a standalone diagnosis but part of a larger regulatory disturbance that must be understood in context [5] [7] [17].

Gut Barrier Dysfunction Without Using Buzzwords

What the gut barrier actually does in normal physiology

The intestinal barrier is a highly regulated interface between the contents of the gut and the internal immune environment of the body. Its role is not to block everything, but to selectively allow nutrients and water to pass while keeping microbes and their byproducts at a safe distance. In healthy digestion, this barrier maintains immune tolerance and prevents unnecessary inflammation. In irritable bowel syndrome, research shows that this regulatory function can become impaired, leading to increased intestinal permeability even in the absence of visible inflammation or tissue damage [8].

How increased permeability develops in IBS

In IBS, gut barrier dysfunction does not usually appear suddenly or dramatically. It often develops gradually due to cumulative stress on the intestinal lining. Factors such as prior gut infections, chronic microbiome imbalance, repeated antibiotic exposure, persistent stress physiology, and altered motility can all weaken barrier regulation over time. From your perspective as a patient, this may not feel like a distinct event but rather a slow increase in food sensitivity, symptom unpredictability, or flare ups that seem out of proportion to dietary changes [8].

Why permeability does not show up on routine tests

One reason gut barrier dysfunction is frequently overlooked is that it does not produce the structural changes that standard investigations are designed to detect. Colonoscopy, imaging, and basic blood tests assess gross inflammation or damage, not subtle permeability shifts at the cellular level. As a result, doctors may reassure patients that the gut lining is normal while the barrier function itself remains compromised. This gap between structure and function is a key reason IBS symptoms persist despite normal reports [8].

How barrier dysfunction triggers immune reactivity

When barrier regulation weakens, luminal contents such as bacterial fragments, metabolites, and partially digested food components gain greater access to immune cells in the gut lining. This does not typically cause acute inflammation, but it can lead to ongoing low grade immune activation. Immune cells respond by releasing mediators that sensitize nerves and alter motility. From the patient’s experience, this may present as heightened sensitivity to foods, stress related flares, or symptoms that shift without a clear trigger. From a clinical standpoint, this immune response explains why IBS can behave like an inflammatory condition without meeting criteria for inflammatory bowel disease [6].

Why both patients and doctors underestimate this mechanism

At the ground level, patients may struggle to accept barrier dysfunction as a real problem because test results appear normal. Doctors may also hesitate to pursue this line of reasoning because permeability is difficult to measure directly and lacks standardized clinical thresholds. In addition, discussions around barrier dysfunction are often avoided or oversimplified due to confusion with non medical terminology, leading clinicians to dismiss the concept rather than explain it properly. This results in missed opportunities to connect immune reactivity, microbiome imbalance, and symptom persistence [6].

Research level limitations that slow clinical adoption

From a research perspective, gut barrier function is complex and dynamic. Permeability varies with stress, sleep, diet, circadian rhythm, and microbial activity. This variability makes it difficult to define universal cutoffs or create simple diagnostic tools. Many studies therefore demonstrate association rather than direct causation, which slows translation into routine guidelines. Despite this, the biological link between barrier dysfunction, immune activation, and IBS symptoms is increasingly well supported [8] [6].

Why gut barrier dysfunction matters in the IBS framework

When gut barrier dysfunction is recognized as part of IBS pathophysiology, many otherwise confusing symptoms begin to make sense. Food sensitivity, symptom fluctuation, stress related flares, and overlap with immune mediated complaints can all be explained without invoking psychological weakness or unexplained functional labels. For patients, this understanding validates lived experience. For clinicians, it reinforces that IBS involves altered regulation at the gut immune interface, not just abnormal bowel habits. Addressing barrier dysfunction is therefore central to breaking the cycle of ongoing immune activation and symptom persistence [8] [6].

Immune Activation and Low Grade Inflammation

IBS involves immune signaling even without classic inflammation

In irritable bowel syndrome, immune activity is often altered despite the absence of visible inflammation on colonoscopy or abnormal blood markers. This immune activation is subtle and localized rather than widespread or destructive. Immune cells within the gut lining remain in a state of low grade signaling, releasing mediators that influence nerve sensitivity and gut motility. From a biological standpoint, this explains how IBS can produce real pain, urgency, and discomfort without meeting criteria for inflammatory bowel disease. For patients, it clarifies why symptoms feel inflammatory even when doctors say there is no inflammation [6].

How gut barrier dysfunction feeds immune activation

The immune system of the gut is in constant communication with the intestinal barrier. When barrier regulation weakens, luminal contents such as bacterial fragments, metabolites, and partially digested food components interact more closely with immune cells. This interaction does not usually trigger acute inflammation, but it sustains ongoing immune activation that keeps the gut in a reactive state. From a clinical perspective, this barrier immune interaction explains why IBS symptoms fluctuate with diet, stress, or illness rather than following a predictable pattern. For patients, it explains why symptoms can worsen without an obvious trigger [8].

Mast cells and their proximity to gut nerves

One of the most important discoveries in IBS research is the role of mast cells located close to gut nerves. Mast cells are immune cells that release substances capable of sensitizing nearby nerves. Studies have shown that in IBS, mast cells are often found in increased numbers or positioned unusually close to intestinal nerve endings. This proximity allows immune mediators to directly amplify pain signals and alter gut function. From the doctor’s perspective, this explains why IBS pain can be intense even without tissue damage. From the patient’s experience, it explains why discomfort can feel sharp, burning, or disproportionate to physical findings [9].

Why immune activation is commonly overlooked in practice

In routine clinical care, immune activation in IBS is often overlooked because it does not present with elevated inflammatory markers or obvious lesions. Doctors are trained to associate immune involvement with clear laboratory abnormalities. When these are absent, immune mechanisms are often dismissed. Patients may also resist immune explanations because they fear being labeled with a serious inflammatory disease. This mutual misunderstanding allows low grade immune activation to remain unaddressed, even though it plays a central role in symptom persistence [6].

Research level challenges in defining low grade inflammation

From a research standpoint, low grade immune activation is difficult to quantify. Immune signaling in IBS is dynamic and localized, varying across gut regions and fluctuating over time. This makes it hard to capture using single blood tests or biopsies. Many studies therefore rely on indirect markers or associations, which slows incorporation into formal guidelines. Despite these challenges, the consistency of findings linking immune activation, barrier dysfunction, and nerve sensitization has strengthened the scientific basis for immune involvement in IBS [6] [8] [9].

Why immune activation completes the IBS puzzle

When immune activation is considered alongside microbiome imbalance, gut barrier dysfunction, and nervous system dysregulation, IBS becomes a coherent biological condition rather than a vague functional label. For patients, this perspective validates symptoms that have long been dismissed. For clinicians, it explains why treating only bowel habits or stress rarely produces lasting relief. Immune activation acts as a sustaining force that keeps the gut hypersensitive and reactive, reinforcing the chronic nature of IBS when underlying mechanisms are not addressed [6] [8] [9].

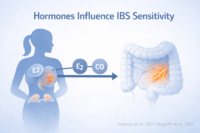

Hormonal Influences Doctors Rarely Map Properly

Why IBS affects women more frequently

Irritable bowel syndrome shows a clear female predominance, which cannot be explained by psychology alone. Sex hormones play a direct role in gut motility, pain perception, immune signaling, and gut brain communication. Estrogen and progesterone influence how quickly the intestines move, how sensitive gut nerves become, and how the immune system responds within the intestinal lining. As a patient, you may notice that symptoms fluctuate with the menstrual cycle, worsen before periods, or change during pregnancy or menopause. From a clinical standpoint, these patterns reflect hormone driven physiological shifts rather than coincidence or heightened emotional sensitivity [10].

How hormonal fluctuations amplify gut sensitivity

Hormonal levels do not remain constant. Monthly cycles, life stages, and endocrine transitions all affect gut behavior. During phases of hormonal fluctuation, gut nerves may become more reactive and immune signaling may intensify. This can lead to increased bloating, pain, constipation, or diarrhea even when diet and lifestyle remain unchanged. For doctors, failure to map symptoms against hormonal patterns often leads to incomplete explanations. For patients, it explains why IBS feels unpredictable and resistant to standard dietary advice [10].

Cortisol and stress hormone dysregulation in IBS

Cortisol is a key stress hormone that regulates immune activity, metabolism, and nervous system balance. In IBS, cortisol signaling is often dysregulated rather than simply elevated. Some individuals experience exaggerated stress responses, while others show a blunted or poorly timed cortisol rhythm. From your perspective, this may appear as symptom flares during pressure, fatigue after stress, poor sleep, or slow recovery after illness. From a biological standpoint, abnormal cortisol signaling directly alters gut motility, barrier function, immune reactivity, and pain processing [11].

Why hormonal assessment is often skipped in practice

In routine gastrointestinal care, hormonal evaluation is rarely considered unless obvious endocrine disease is suspected. Doctors often assume hormones are relevant only to reproductive health, not digestive function. Patients may also hesitate to discuss menstrual patterns, fatigue, or stress related symptoms in gastroenterology settings, believing they are unrelated. This mutual blind spot leads to missed connections between hormone regulation and gut dysfunction, especially in women with long standing or fluctuating IBS [10] [11].

Ground level factors that deepen hormonal imbalance

At the ground level, modern lifestyle factors further disturb hormonal regulation. Poor sleep, irregular eating schedules, chronic psychological pressure, and repeated illness all disrupt circadian hormone rhythms. Women may be prescribed hormonal medications without considering gut sensitivity, while men may experience cortisol driven IBS symptoms that go unrecognized because IBS is viewed as a female condition. These practical realities compound underlying hormonal vulnerability and reinforce symptom persistence [11].

Research level gaps that limit clinical translation

From a research perspective, hormonal influences in IBS are complex and difficult to isolate. Hormones interact with the nervous system, immune system, and microbiome simultaneously. This makes it challenging to design single variable studies with clear endpoints. Many trials therefore acknowledge hormonal influence without integrating it into diagnostic or treatment frameworks. As a result, hormonal mapping remains underutilized in routine IBS care despite consistent evidence of its relevance [10].

Why hormones complete the regulatory picture of IBS

When hormonal influences are considered alongside gut brain axis dysfunction, immune activation, microbiome imbalance, and barrier dysfunction, IBS emerges as a disorder of regulation rather than a local bowel problem. For patients, this understanding validates why symptoms fluctuate across life stages and stress levels. For clinicians, it highlights why ignoring hormonal context leads to partial explanations and limited outcomes. Properly mapping hormonal influence is essential to understanding why IBS persists and why one size fits all treatment approaches repeatedly fail [10] [11].

Sleep, Circadian Rhythm, and Digestive Timing

How sleep regulates gut function through autonomic rhythms

Sleep is not a passive state for the digestive system. During healthy sleep, autonomic nervous system activity shifts toward parasympathetic dominance, allowing the gut to rest, repair, and coordinate motility patterns. In irritable bowel syndrome, this rhythm is often disrupted. Autonomic imbalance during sleep leads to irregular gut contractions, altered secretion, and impaired overnight regulation. From a patient’s perspective, this may appear as early morning urgency, incomplete bowel movements, or waking with bloating despite fasting overnight. From a physiological standpoint, disrupted autonomic rhythm during sleep directly interferes with digestive timing and recovery [3].

The stress, sleep, and gut interaction cycle

Sleep disturbance and stress physiology reinforce each other in IBS. Poor sleep activates stress pathways, while stress hormones further impair sleep quality. This cycle has direct consequences for gut function. When stress signaling remains active overnight, cortisol rhythms become dysregulated, immune activity remains heightened, and gut nerves stay sensitized. As a result, the digestive system never fully resets. You may notice that a single night of poor sleep can trigger symptoms the following day, even without dietary changes. Clinically, this reflects a stress sleep gut loop rather than isolated insomnia or anxiety [11].

Why sleep problems worsen IBS symptoms

Research consistently shows that sleep disturbance is associated with increased IBS symptom severity. Fragmented sleep, reduced deep sleep, and irregular sleep timing all correlate with worse pain, bloating, and bowel irregularity. From the patient’s experience, symptoms often feel more intense and less controllable after poor sleep. From the clinician’s viewpoint, this explains why symptom control fluctuates even when treatment remains unchanged. Sleep disruption does not merely coexist with IBS, it actively worsens the condition by amplifying nervous system and immune reactivity [12].

Digestive timing and circadian misalignment

The digestive system follows circadian patterns that coordinate enzyme release, motility, and microbial activity. When sleep timing is irregular, these digestive rhythms fall out of sync. Late nights, shift work, frequent travel, and inconsistent meal timing disrupt normal gut cycles. For patients, this may present as unpredictable bowel habits or symptoms that worsen at specific times of day. Clinically, circadian misalignment explains why some individuals develop IBS symptoms despite normal diet and test results, particularly when lifestyle rhythms are chronically disturbed [3].

Why sleep is often underestimated in IBS care

In routine practice, sleep is often treated as a lifestyle issue rather than a core physiological regulator. Doctors may ask about stress or diet but overlook sleep quality and timing. Patients may also normalize poor sleep and fail to mention it unless directly asked. This leads to missed opportunities to recognize sleep disruption as a driving force behind symptom persistence. Without addressing sleep related autonomic and hormonal dysregulation, other interventions often produce only partial or temporary relief [11] [12].

Research level challenges in linking sleep and IBS

From a research perspective, sleep related effects on IBS are difficult to isolate. Sleep quality varies night to night and is influenced by stress, environment, and behavior. Many studies rely on self reported sleep measures rather than objective monitoring. Despite these challenges, consistent evidence links poor sleep with worse IBS outcomes, supporting its role as a key regulatory factor rather than a secondary complaint [3] [11] [12].

Why restoring sleep rhythm matters for long term improvement

When sleep and circadian rhythm are stabilized, the digestive system gains the opportunity to recalibrate. For patients, this often leads to reduced symptom volatility and improved baseline comfort. For clinicians, it reinforces that IBS management must consider timing and regulation, not just food and medication. Recognizing sleep as a central regulator completes the picture of IBS as a disorder of disrupted biological rhythms rather than an isolated gut problem [3] [11] [12].

Medication Induced IBS and Gut Damage

How commonly used medications alter gut physiology

Many people develop IBS symptoms after prolonged or repeated exposure to medications that interfere with normal digestive regulation. These effects are rarely discussed during routine consultations because the medications are often considered safe and necessary for short term use. Over time, however, certain drugs can alter gut motility, microbial balance, immune signaling, and barrier function. From the patient’s perspective, symptoms may begin gradually and are often not linked to medication use because the onset feels delayed rather than immediate. From a biological standpoint, medication induced changes can act as silent triggers that sustain IBS symptoms long after the original reason for prescribing the drug has passed [5] [13].

Proton pump inhibitors and microbiome disruption

Proton pump inhibitors are widely prescribed for acidity, reflux, and gastritis. By suppressing stomach acid, these medications change one of the body’s primary defenses against abnormal microbial growth. Reduced acid allows bacteria to survive and migrate into regions of the gut where they do not normally dominate. This shift alters microbial composition and fermentation patterns downstream. For patients, this may present as bloating, gas, altered bowel habits, or food sensitivity developing months after starting therapy. Clinically, this microbiome disruption helps explain why IBS like symptoms may emerge or worsen despite apparent control of acid related complaints [13].

Antibiotics and long term dysbiosis

Antibiotics are among the strongest disruptors of gut microbial balance. While they are often lifesaving, they do not distinguish between harmful and beneficial organisms. Repeated or broad spectrum antibiotic exposure can lead to long lasting dysbiosis, reduced microbial diversity, and impaired resilience of the gut ecosystem. From your perspective as a patient, digestion may feel different after antibiotic courses, with new sensitivities or irregular bowel patterns emerging. From a clinical standpoint, antibiotic induced dysbiosis is a well recognized precursor to IBS, particularly when recovery of the microbiome is incomplete [5].

Why medication related causes are frequently overlooked

In everyday practice, doctors often focus on the immediate benefit of medications and may not revisit their long term digestive effects once treatment goals are met. Patients may also hesitate to question medications they were told were necessary or safe. When IBS symptoms appear later, the link to prior medication exposure is easily missed. This delay reinforces the belief that IBS arose spontaneously rather than as a consequence of cumulative physiological disruption [5] [13].

Ground level clinical dynamics that reinforce the problem

At the ground level, medications such as acid suppressants and antibiotics are frequently prescribed without long term follow up regarding gut health. Time constraints limit discussion of digestive side effects unless symptoms are severe. Patients may move between providers, making it difficult to trace medication history accurately. These practical realities allow medication induced gut changes to persist unnoticed while symptoms continue [5].

Research level gaps in medication related IBS recognition

From a research perspective, medication induced IBS is difficult to study because effects may emerge months or years after exposure. Many trials focus on short term outcomes and do not track long term gut regulation or microbiome recovery. In addition, medication effects often overlap with other IBS drivers such as infection, stress, and hormonal changes, making it challenging to isolate causality. Despite this, accumulating evidence supports a strong link between certain medications, dysbiosis, and persistent functional gut symptoms [5] [13].

Why medication history matters in IBS evaluation

When medication exposure is carefully mapped, many otherwise unexplained IBS cases become clearer. For patients, this understanding removes confusion about why symptoms appeared after treatment rather than illness. For clinicians, it reinforces the need to consider long term gut regulation when prescribing and reviewing medications. Recognizing medication induced gut disruption is essential to understanding why IBS persists and why symptom focused treatment alone often fails [5] [13].

Dietary Restriction Cycles and Nutrient Signaling Failure

How repeated dietary restriction reshapes gut behavior

Many people with irritable bowel syndrome enter cycles of dietary restriction in an effort to control symptoms. Foods are removed one by one, often without a clear reintroduction plan. Initially, symptoms may improve due to reduced gut stimulation. Over time, however, repeated restriction alters how the digestive system senses and responds to nutrients. From your perspective as a patient, digestion may begin to feel fragile, with fewer foods tolerated and symptoms triggered by small deviations. From a physiological standpoint, the gut adapts to scarcity rather than balance, leading to impaired regulatory signaling rather than true healing.

Why short term relief leads to long term sensitivity

When large food groups are removed for extended periods, the gut receives less variety of nutrients that normally stimulate coordinated motility, enzyme release, and microbial activity. This can slow digestive responsiveness and reduce tolerance thresholds. As foods are reintroduced, the gut may respond with exaggerated symptoms, reinforcing fear and further restriction. Clinically, this pattern explains why patients often feel trapped between symptom flare ups and increasingly narrow diets, even when no structural disease is present.

Nutrient signaling and gut brain communication

The digestive system relies on nutrient sensing to coordinate movement, secretion, and feedback to the brain. Carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and micronutrients each trigger specific gut signals that regulate satiety, motility, and immune tolerance. When diets become overly restrictive, these signals weaken or become inconsistent. From the patient’s experience, this may present as unpredictable hunger cues, bloating after small meals, or discomfort unrelated to portion size. From a biological viewpoint, disrupted nutrient signaling contributes to ongoing gut brain miscommunication rather than calming the system.

Impact on the gut microbiome and barrier regulation

Dietary variety is a major driver of microbial diversity. Prolonged restriction reduces the substrates available to beneficial microbes, leading to further imbalance. This microbial shift can impair barrier regulation and immune tolerance, making the gut more reactive to foods that were previously safe. For patients, this may feel like developing new intolerances over time. Clinically, it explains why restrictive diets may temporarily reduce symptoms but worsen long term resilience of the digestive system.

Psychological and physiological reinforcement of restriction cycles

As symptoms become linked to specific foods, fear based avoidance can develop even when reactions are inconsistent. This creates a feedback loop where anxiety around eating amplifies gut sensitivity, further reinforcing restriction. Importantly, this process is not purely psychological. Physiological changes in gut signaling and microbial balance make the gut genuinely more reactive. From the doctor’s perspective, focusing only on dietary avoidance without restoring signaling and tolerance often deepens the problem rather than resolving it.

Why this mechanism is often missed in IBS care

In clinical practice, dietary restriction is frequently encouraged without long term planning. Patients are praised for identifying trigger foods but are rarely guided on how to rebuild tolerance. Because restrictive diets can reduce symptoms in the short term, their deeper regulatory consequences are overlooked. Over time, both patient and clinician may mistake narrowing tolerance for disease progression rather than an adaptive response to prolonged restriction.

Why restoring nutrient signaling is essential for recovery

When nutrient signaling is restored through gradual reintroduction and diversity, the gut has the opportunity to recalibrate. For patients, this often reduces fear around food and improves baseline comfort. For clinicians, it reinforces that IBS management should aim to restore regulation rather than enforce avoidance. Recognizing dietary restriction cycles as a driver of ongoing dysfunction helps explain why symptom control alone does not lead to lasting improvement and why rebuilding tolerance is as important as identifying triggers.

Emotional Suppression and Trauma Physiology

How emotional states are encoded through the gut brain axis

Emotional experiences are not processed only in the mind. They are biologically encoded through continuous signaling between the brain, autonomic nervous system, and gut. In irritable bowel syndrome, this gut brain axis becomes a pathway through which unresolved emotional stress is translated into altered motility, heightened sensitivity, and persistent discomfort. This process is not conscious or intentional. From your perspective as a patient, symptoms may arise without clear emotional triggers. From a biological standpoint, stress related signals become embedded in gut regulation through neural and hormonal pathways rather than through deliberate thought [1].

Emotional suppression as a physiological load rather than a psychological choice

Emotional suppression does not mean ignoring emotions or denying feelings on purpose. It often develops as a survival response to prolonged stress, trauma, social pressure, or the need to remain functional under difficult circumstances. When emotional expression is repeatedly inhibited, stress signaling remains active in the body even when the external situation appears calm. For the gut, this means sustained autonomic imbalance, altered motility, and increased nerve sensitivity. From a clinical perspective, this explains why patients may report IBS symptoms despite describing themselves as emotionally stable or resilient [11].

Chronic stress physiology and its effects on digestion

Chronic stress alters hormonal and nervous system regulation over time. Stress hormones such as cortisol become dysregulated, either remaining elevated or losing their normal daily rhythm. This dysregulation directly affects gut movement, immune signaling, barrier function, and pain processing. From your experience, this may feel like digestive symptoms that worsen during life pressure, poor sleep, or emotional exhaustion rather than during acute anxiety. Clinically, this reflects a state of chronic physiological stress rather than short term emotional distress [11].

How trauma physiology amplifies pain sensitivity

One of the most consistent findings in IBS is pain hypersensitivity. This is not limited to the gut but reflects broader nervous system sensitization. When the body remains in a prolonged state of threat response, sensory pathways become more reactive. Gut sensations that would normally be perceived as neutral are interpreted as painful or urgent. From the doctor’s perspective, this explains why pain severity often does not correlate with physical findings. From the patient’s perspective, it explains why discomfort can feel intense, intrusive, and difficult to control [14].

Why emotional and trauma related physiology is often misunderstood

In clinical practice, discussions around emotion and trauma are often avoided or oversimplified. Doctors may hesitate to explore these areas for fear of appearing dismissive or psychological. Patients may resist such discussions because they worry their symptoms will be labeled as imaginary or stress induced. This mutual discomfort prevents a clear explanation of how emotional physiology affects gut regulation. As a result, emotional suppression is often framed incorrectly as a personality trait rather than as a biological process with measurable effects [1] [11].

Ground level realities that reinforce this mechanism

At the ground level, many patients with IBS have lived for years under high responsibility, unresolved grief, interpersonal strain, or chronic pressure without adequate recovery time. These experiences may never be discussed in medical settings. Time limited consultations and symptom focused questioning further reduce opportunities to explore long term stress patterns. This allows trauma related physiological imprinting to persist unnoticed while symptoms continue [11].

Research level challenges in linking trauma physiology and IBS

From a research perspective, trauma related mechanisms are difficult to study using conventional biomedical models. Emotional stress, trauma history, and coping patterns are complex, individualized, and often underreported. Many studies rely on questionnaires rather than physiological measurements, which limits precision. Despite these challenges, consistent evidence links chronic stress physiology, altered gut brain signaling, and pain hypersensitivity in IBS populations [1] [14].

Why acknowledging trauma physiology changes the IBS narrative

When emotional suppression and trauma physiology are understood as biological processes, IBS is no longer reduced to a stress related complaint. For patients, this reframing removes blame and validates lived experience. For clinicians, it explains why standard treatments aimed only at bowel habits often fail. Emotional and trauma related physiology acts as a sustaining force that keeps the gut hypersensitive and dysregulated, reinforcing IBS unless the broader regulatory systems are acknowledged [1] [11] [14].

Psychological Stress Without Psychological Blame

Stress affects gut regulation through biology, not personality

Psychological stress in irritable bowel syndrome is often misunderstood as a personality issue or an inability to cope. In reality, stress acts through well defined biological pathways that regulate digestion, immunity, and nerve sensitivity. When stress signaling remains active, the nervous system shifts toward heightened vigilance. This alters gut motility, increases pain perception, and disrupts immune balance. From your perspective as a patient, symptoms may worsen during pressure, uncertainty, or prolonged responsibility even when you feel emotionally resilient. From a physiological standpoint, this reflects stress driven regulatory changes rather than weakness or imagination.

Why stress does not mean symptoms are imagined

Many patients are told that stress causes their symptoms in a way that feels dismissive. This framing implies that if stress were managed better, symptoms would disappear. What is often missed is that stress physiology operates independently of conscious thought. Even when you do not feel anxious, your body may remain in a heightened state due to chronic demands, unresolved illness, poor sleep, or past infections. Gut nerves, immune cells, and microbial signaling all respond to this internal state. Symptoms are therefore real biological outputs, not emotional exaggerations.

How chronic stress sensitizes the gut over time

Short term stress can temporarily change digestion. Chronic stress, however, reshapes gut behavior. Repeated activation of stress pathways sensitizes gut nerves, alters immune signaling, and weakens barrier regulation. Over time, the gut becomes more reactive to normal stimuli such as meals, bowel distension, or daily routines. From the patient’s experience, this may feel like a gradual loss of digestive tolerance rather than sudden illness. Clinically, it explains why IBS often becomes persistent even after the original trigger has passed.

Why stress explanations often feel invalidating

At the ground level, stress is frequently used as a catch all explanation when tests are normal. Patients may feel blamed or unheard, while doctors may believe they are offering reassurance. This mismatch damages trust. Stress should be explained as a biological amplifier that interacts with gut brain signaling, immune activation, microbiome balance, and sleep rhythms. When framed correctly, stress becomes one part of a regulatory system rather than the sole cause of symptoms.

The role of learned gut threat responses

Over time, the gut can learn to anticipate discomfort. Past painful episodes, unpredictable flares, or fear around eating can condition the nervous system to remain alert. This learned response does not require conscious anxiety. It is an automatic protective mechanism that keeps gut sensitivity elevated. From your perspective, symptoms may appear without obvious triggers. From a biological viewpoint, this reflects nervous system conditioning rather than psychological weakness.

Why separating mind and gut delays progress

When stress is treated as a mental issue separate from digestion, care becomes fragmented. Patients may be referred away from gut focused evaluation, while biological drivers remain active. Conversely, when stress physiology is integrated into gut regulation, it becomes possible to explain why symptoms fluctuate with life demands, recovery time, and internal load. This integrated view removes blame and replaces it with understanding.

How this perspective changes patient experience

When psychological stress is explained without blame, patients often feel relief rather than dismissal. You are no longer told that symptoms exist because you worry too much. Instead, you are shown how the body responds to prolonged demand and why the gut is particularly sensitive to these signals. This understanding supports engagement with care rather than resistance and allows stress regulation to be approached as a biological recalibration rather than a personal failure.

Why stress belongs in IBS care without stigma

Stress is not the cause of IBS on its own, but it is a powerful regulator that can sustain symptoms when other systems are already vulnerable. Recognizing this allows patients and clinicians to address stress physiology without minimizing microbiome imbalance, immune activation, barrier dysfunction, or nervous system sensitivity. When blame is removed, stress becomes a legitimate and necessary part of understanding why IBS persists and why recovery requires restoring regulation rather than suppressing symptoms.

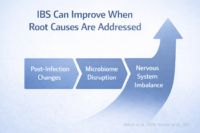

Why Treating IBS as One Disease Always Fails and Where to Look for a Complete Cure

IBS is not a single disorder but a convergence of multiple disrupted systems

When all the preceding sections are viewed together, a clear pattern emerges. IBS is not one disease with one cause. It is the final expression of multiple overlapping disturbances involving gut brain signaling, autonomic imbalance, microbiome dysbiosis, immune activation, barrier dysfunction, hormonal regulation, sleep rhythm disruption, medication effects, dietary restriction cycles, and stress physiology. Treating IBS as a single gut problem inevitably leads to partial relief at best and long term frustration at worst.

From your perspective as a patient, this explains why one treatment works briefly and then fails, or why different doctors offer conflicting advice. From a clinical standpoint, it explains why symptom based classifications alone do not capture the true drivers of the condition.

Why conventional IBS treatment remains fragmented

Most conventional approaches focus on isolated targets such as bowel movement frequency, pain suppression, or stress management. Laxatives, antispasmodics, antidepressants, probiotics, elimination diets, or reassurance are often prescribed independently rather than as part of a unified regulatory framework. This fragmented approach fails to address the interconnected nature of IBS pathophysiology. When one system is targeted in isolation, other dysregulated systems continue to drive symptoms.

Doctors are not wrong in using these tools, but they are incomplete when applied without understanding the full biological context.

The need for a systems based, root focused framework

A meaningful path forward requires viewing IBS as a systems disorder rather than a functional label. This means identifying which regulatory loops are disrupted in a given individual and addressing them in a coordinated way. Some patients are driven primarily by post infectious changes, others by microbiome collapse, others by autonomic dominance, hormonal fluctuation, or long term medication effects. Without this differentiation, treatment becomes trial and error rather than targeted care.

Where comprehensive understanding and curative intent come together

For readers who are looking beyond symptom control and want to understand how IBS can be approached at the root level, a detailed, integrated framework is essential. This includes diagnosis, mechanism mapping, individualized correction, and long term regulation rather than short term suppression.

A complete, structured explanation of this approach, including diagnosis, symptom patterns, and curative direction, is covered in the pillar resource below: https://panaceayur.com/ibs-ayurvedic-treatment-diagnosis-symptoms-cure/

Why Standard IBS Tests Miss These Causes

Functional labeling creates a diagnostic blind spot

Irritable bowel syndrome is still largely categorized under the umbrella of functional gastrointestinal disorders. While the Rome IV framework improved conceptual understanding by introducing the gut brain interaction model, the functional label continues to influence how testing is approached in practice. Once IBS is assigned this label, further investigation often stops prematurely. From the doctor’s perspective, the absence of structural disease appears to confirm the diagnosis. From the patient’s experience, this can feel like a dead end, where symptoms are acknowledged but underlying causes are no longer explored. This diagnostic gap allows complex biological drivers to remain unrecognized [2].

What standard tests are designed to detect and what they are not

Colonoscopy, routine blood tests, imaging, and basic stool examinations are designed to identify visible pathology such as inflammation, ulcers, tumors, bleeding, or infection. They are effective tools for ruling out serious disease, but they are not designed to assess regulation. Gut brain signaling dysfunction, autonomic imbalance, microbiome shifts, immune sensitization, barrier permeability changes, and hormonal influences do not produce the structural abnormalities these tests are meant to detect. As a result, normal findings are expected in IBS, even when symptoms are severe and persistent [17].

Why normal results are often misinterpreted as absence of disease

When test results fall within normal ranges, both patients and doctors may interpret this as proof that nothing is wrong. Clinically, this leads to reassurance rather than deeper inquiry. Patients may feel invalidated, while doctors may feel confident that further workup is unnecessary. The problem is not that the tests are wrong, but that they are being asked to answer questions they were never designed to address. IBS is a disorder of regulation, sensitivity, and signaling, not one of gross structural damage [2].

The gap between symptoms and measurable markers

Many of the core IBS mechanisms operate at a microscopic or functional level. Immune activation may be localized and low grade, nerve sensitization may occur without tissue injury, and microbiome imbalance may involve shifts in function rather than presence of pathogens. These changes fall outside the resolution of standard diagnostics. From the patient’s perspective, this creates confusion. Symptoms are real and disruptive, yet repeatedly dismissed because they cannot be visualized or quantified using routine tools [17].

Why further testing is rarely pursued

Once serious disease is excluded, there is often little incentive to continue investigation within conventional pathways. Doctors may worry about over testing, patients may feel exhausted by repeated normal results, and healthcare systems may not support deeper functional evaluation. Over time, this reinforces a cycle where IBS is managed symptom by symptom rather than explored mechanistically. The diagnostic process stops not because causes are absent, but because available tools are limited [2] [17].

How understanding test limitations changes the conversation

When patients understand what standard tests can and cannot detect, the experience of normal results shifts. Normal tests no longer mean symptoms are imagined or insignificant. Instead, they indicate that the problem lies in regulation rather than structure. For clinicians, this perspective encourages more thoughtful interpretation of results and avoids premature closure. For patients, it restores trust and opens the door to approaches that address underlying drivers rather than endlessly repeating investigations that were never designed to find them [2] [17].

IBS Overlap With Other Chronic Conditions

Why IBS rarely exists in isolation

Irritable bowel syndrome often overlaps with other chronic conditions rather than appearing as a standalone disorder. This overlap is not coincidental. Many of the same biological mechanisms that drive IBS also influence pain processing, immune signaling, and nervous system regulation throughout the body. From a patient’s perspective, this may feel like multiple unrelated diagnoses accumulating over time. From a clinical standpoint, it reflects shared underlying pathways rather than separate diseases developing independently [15].

Immune and neurological pathways link IBS to other conditions

One of the strongest connections between IBS and other chronic disorders lies in immune neurological interaction. Low grade immune activation can sensitize nerves not only in the gut but also in other tissues. This shared sensitization helps explain why IBS frequently coexists with conditions involving chronic pain, fatigue, or sensory amplification. Research shows that immune mediators released in the gut can influence neural circuits that regulate pain perception more broadly, creating a systemic pattern of heightened sensitivity rather than a local gut problem [9].

Common conditions that overlap with IBS

IBS is frequently reported alongside disorders such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue states, migraine, pelvic pain syndromes, and functional urological complaints. Anxiety and mood disturbances also commonly coexist, not as primary causes but as parallel outcomes of shared nervous system dysregulation. From the patient’s experience, this overlap may feel overwhelming or confusing, especially when each condition is treated separately. Clinically, it indicates that IBS is part of a broader regulatory disturbance affecting multiple systems [15].

Why overlap complicates diagnosis and treatment

When IBS overlaps with other chronic conditions, diagnosis often becomes fragmented. Patients may see different specialists for each symptom cluster, with little coordination between care pathways. Each condition is addressed in isolation, while the shared drivers remain untouched. From a medical perspective, this fragmentation makes it difficult to achieve lasting improvement. From the patient’s viewpoint, it reinforces the sense of having multiple unsolved problems rather than one interconnected condition [15].

Why overlap is often dismissed or minimized

Overlap syndromes are sometimes minimized because they do not fit neatly into structural disease categories. Doctors may attribute them to stress, personality, or heightened symptom awareness rather than shared biological mechanisms. Patients may also hesitate to report all symptoms, fearing they will not be taken seriously. This mutual hesitation delays recognition of the broader pattern linking IBS with other chronic disorders [9].

How recognizing overlap changes understanding

When IBS is understood in the context of immune neurological overlap, the broader symptom picture becomes clearer. Multiple diagnoses no longer appear random or psychosomatic. Instead, they reflect a system under prolonged regulatory strain. For patients, this perspective validates lived experience and reduces self blame. For clinicians, it encourages integrated thinking rather than siloed management, improving the chances of meaningful progress [9] [15].

Why overlap reinforces the need for a systems approach

The frequent coexistence of IBS with other chronic conditions reinforces a central conclusion. IBS cannot be fully understood or managed as a gut only disorder. Its overlap with immune and neurological conditions highlights the need for approaches that address regulation across systems rather than suppressing symptoms in one organ at a time. Recognizing this overlap is a critical step toward explaining why IBS persists and why resolution requires a broader biological framework [9] [15].

Prognosis, Reversibility, and Recovery Factors

Why IBS prognosis varies widely between individuals

The course of irritable bowel syndrome differs significantly from one person to another. Some individuals experience gradual improvement over time, while others live with persistent or fluctuating symptoms for many years. This variability is not random. Prognosis is strongly influenced by the underlying drivers of IBS, particularly whether symptoms began after an infection, developed gradually, or were shaped by long standing regulatory stress. From a patient’s perspective, this explains why comparisons with others can feel misleading. From a clinical standpoint, it highlights that IBS does not follow a single predictable timeline [16].

Post infectious IBS and long term outcomes

Among the different IBS subtypes, post infectious IBS has been studied extensively in terms of prognosis. Research shows that while some patients recover gradually, others continue to experience symptoms long after the initial infection has resolved. The likelihood of recovery depends on the degree of immune activation, nervous system sensitization, and microbiome disruption left behind by the infection. When these changes persist, symptoms tend to remain chronic rather than self resolving. For patients, this explains why reassurance after infection does not always translate into recovery [4].

The role of sleep in symptom persistence and recovery

Sleep quality plays a critical role in determining whether IBS improves or worsens over time. Poor sleep maintains autonomic imbalance, disrupts hormonal rhythms, and sustains immune activation. Studies show that individuals with ongoing sleep disturbance tend to report more severe symptoms and slower improvement. Conversely, when sleep patterns stabilize, symptom volatility often decreases. From the patient’s experience, this explains why progress may stall during periods of poor rest even when diet and treatment remain unchanged [12].

Why IBS is often reversible but rarely spontaneously cured

IBS is not a degenerative condition, and structural damage does not typically progress over time. This means that, biologically, the condition is often reversible. However, reversal rarely occurs spontaneously. Without addressing the regulatory loops involving gut brain signaling, immune activation, microbiome balance, sleep rhythm, and stress physiology, the system tends to remain locked in a reactive state. From a clinical perspective, this explains why IBS may persist for years despite repeated reassurance and symptomatic treatment [16].

Factors that improve the likelihood of recovery

Recovery is more likely when underlying drivers are recognized early and addressed systematically. This includes identifying post infectious triggers, restoring sleep rhythm, reducing autonomic overactivation, rebuilding microbial balance, and correcting dietary restriction cycles. Patients who receive explanations that validate symptoms and guide gradual regulation tend to engage more effectively with care. Clinically, prognosis improves when IBS is treated as a regulatory condition rather than a lifelong functional label [4] [12].

Why delayed recognition worsens prognosis

The longer IBS persists without targeted intervention, the more deeply regulatory patterns become ingrained. Chronic nerve sensitization, immune signaling, and behavioral adaptations reinforce each other over time. Patients may lose confidence in recovery and adapt their lives around symptoms. From a biological standpoint, this does not make recovery impossible, but it does make it slower. Early recognition and intervention therefore play a key role in improving long term outcomes [16].

A realistic perspective on recovery

Recovery from IBS should be viewed as a process rather than a single intervention. Symptoms often improve gradually as regulatory balance is restored across systems. For patients, this perspective reduces frustration and unrealistic expectations. For clinicians, it reinforces the importance of long term planning rather than short term symptom suppression. When the drivers discussed throughout this article are addressed together, IBS can move from a chronic burden toward meaningful and lasting improvement [4] [12] [16].

When to Stop Symptom Management and Look for Root Cause Healing

Why symptom focused care reaches a ceiling

Symptom management has an important place in early IBS care. It can reduce immediate discomfort, provide reassurance, and help patients function day to day. However, when symptoms persist despite repeated adjustments in diet, medications, or stress advice, symptom control alone reaches a natural limit. From a biological standpoint, ongoing symptoms signal that deeper regulatory systems remain disrupted. Continuing to rotate treatments aimed only at bowel habits or pain often leads to diminishing returns rather than resolution [1].

Signs that symptom management is no longer enough