- What Antiviral Drugs Were Scientifically Designed to Do

- Understanding Herpes Latency in Simple, Clinical Terms

- Why Antiviral Drugs Cannot Act on Dormant Virus

- The Role of Nerve Ganglia as a Protected Viral Reservoir

- Why Daily Suppressive Therapy Does Not Gradually Clear HSV

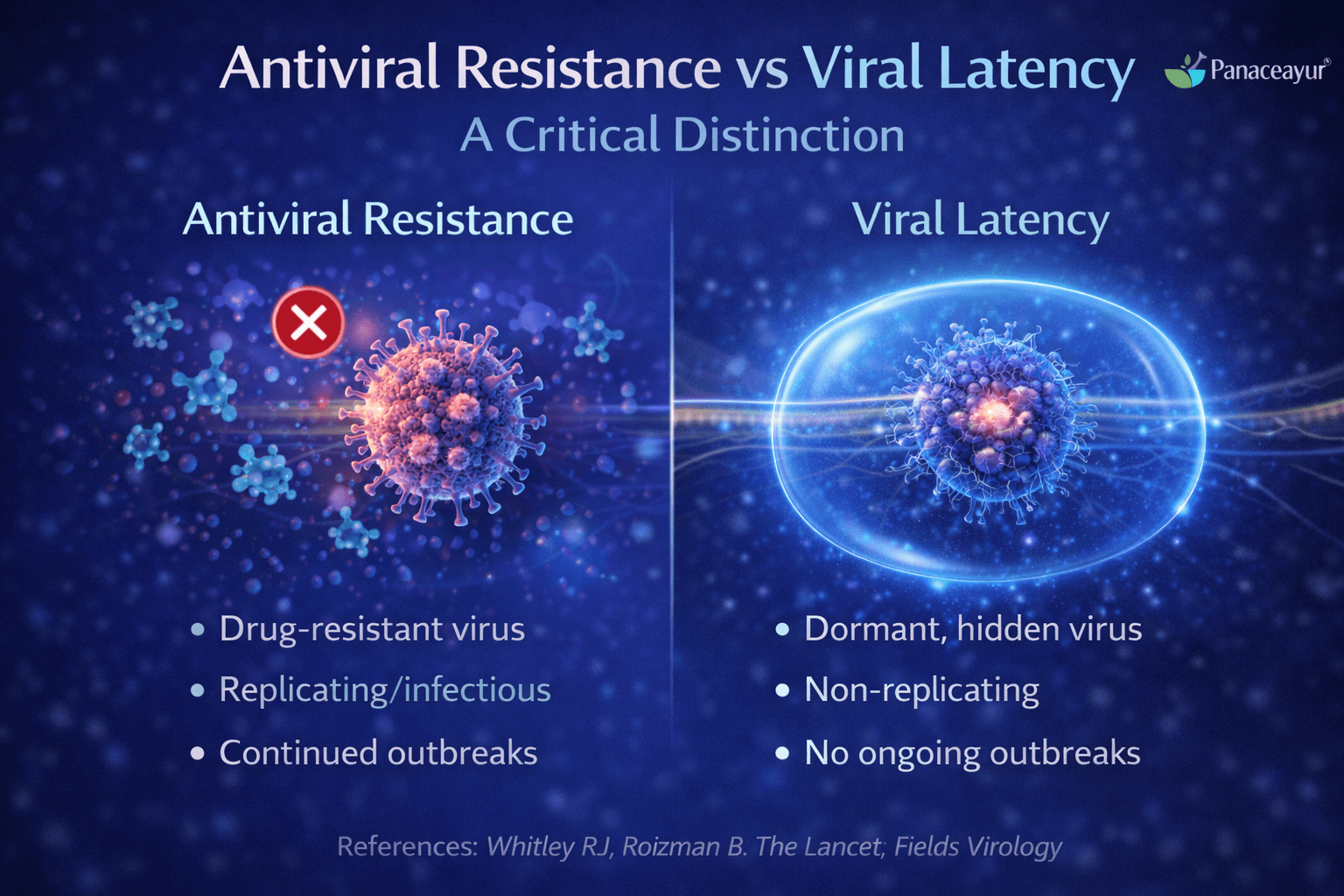

- Antiviral Resistance vs Viral Latency A Critical Distinction

- What Clinical Guidelines Actually Say About Herpes Latency

- Why Doctors Continue Prescribing Antivirals Despite These Limits

- Psychological Impact of the Lifelong Virus Message

- The Difference Between Viral Suppression and Viral Eradication

- Why Research Focus Has Historically Avoided Latency Eradication

- Why “No Cure” Persists as the Default Medical Answer

- How This Section Connects to Broader Healing Models

- FAQs

- Reference

Why antiviral drugs do not eliminate herpes latency from the start

To understand why antiviral drugs do not eliminate herpes latency, it is important to look at how these medicines were originally developed. Antiviral drugs used for herpes, such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir, were designed several decades ago with a very specific medical purpose. Research during the late nineteen seventies and nineteen eighties focused on controlling active infection, not on removing the virus permanently from the body [1].

These medicines belong to a group called nucleoside analog antivirals. Their action is targeted and limited. When the herpes virus becomes active, it needs an enzyme called viral DNA polymerase to copy its genetic material. Antiviral drugs interfere with this enzyme and slow down viral replication [1].

Because of this design, antiviral medicines help reduce the severity of outbreaks. They shorten healing time, reduce pain and irritation, and lower the amount of virus released during active infection. This is the reason they are effective when symptoms are present.

Why antiviral drugs work only during outbreaks

A key reason why antiviral drugs do not eliminate herpes latency is that they work only when the virus is active. During latency, the herpes virus remains inactive inside nerve cells and does not use the replication process that these drugs are designed to block.

When the virus is dormant, viral DNA polymerase is not active. As a result, antiviral medicines have no biological target to act upon [1]. This is why these drugs do not affect the virus during symptom free periods, even if taken daily for long periods.

This behavior does not mean the medicine is weak or ineffective. It means the medicine is working exactly as it was designed to work.

Why cure or eradication was never part of antiviral drug design

Another important reason why antiviral drugs do not eliminate herpes latency is that cure was never part of their original development objective. Scientific literature clearly confirms that herpes antivirals were not created as eradication therapies [4].

At the time these medicines were developed, there was no safe method to remove viral genetic material from nerve cells without causing permanent nerve damage. Because of this, antiviral drugs were approved as suppressive treatments that manage symptoms rather than eliminate the virus [4].

Understanding Herpes Latency in Simple, Clinical Terms

How herpes moves into the nervous system

To understand herpes clearly, it is important to know what happens after the first infection. When herpes simplex virus enters the body, it does not stay only on the skin or mucosal surface where symptoms appear. After the initial infection, the virus travels along sensory nerves and reaches clusters of nerve cells called sensory ganglia [2].

For oral herpes, this usually involves the trigeminal ganglion. For genital herpes, the virus commonly settles in the sacral ganglia. These nerve centers are located deep inside the body and are connected to the areas where herpes symptoms later reappear.

This movement into the nervous system is a normal and expected part of herpes infection, not a complication.

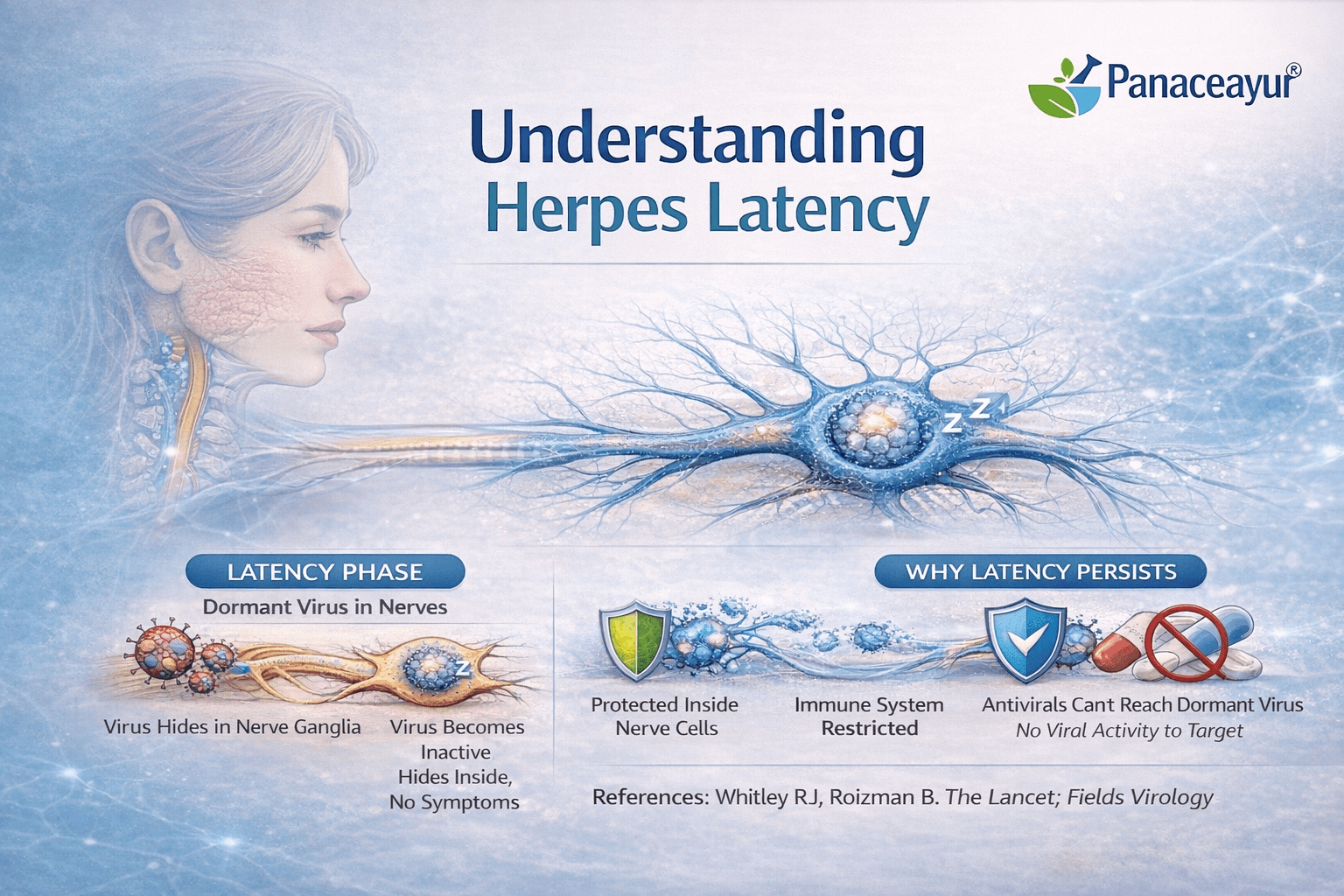

What latency actually means

Once herpes reaches the sensory nerve cells, it enters a state known as latency. Latency means that the virus remains inside the nerve cell but becomes inactive. During this stage, the virus does not multiply, does not cause visible symptoms, and produces very little viral activity [2].

Importantly, the virus is not dead or removed. Its genetic material remains intact inside the nerve cell. Because it is inactive, the immune system does not fully recognize it as a threat, and antiviral drugs cannot act on it.

This dormant state allows the virus to remain in the body for many years, often for life.

Why latency is a natural feature of herpes viruses

Latency is not accidental or unusual. It is a core biological feature of herpesviruses. Scientific research confirms that herpes simplex virus is designed by nature to alternate between inactive and active phases [4].

When conditions in the body change, such as stress, illness, hormonal shifts, or immune weakness, the virus may reactivate. It then travels back along the nerve to the skin or mucosa, where symptoms appear again.

This cycle of dormancy and reactivation explains why herpes can remain silent for long periods and then return unexpectedly.

Why latency does not mean ongoing damage

It is important for patients to understand that during latency, the virus is not actively harming the body. Many people carry latent herpes virus without frequent symptoms or complications.

However, because the virus remains present inside nerve cells, it cannot be fully eliminated by current medical treatments [4]. This explains why herpes is often described as a lifelong infection under modern clinical definitions.

Antiviral medicines are designed to work only during active infection

In the UK and USA, antiviral medicines prescribed for herpes are carefully designed to target the virus only when it is active. These medicines depend on a specific viral process to function. When herpes becomes active, it uses an enzyme called viral DNA polymerase to copy its genetic material and spread to nearby cells. Antiviral drugs interrupt this process and slow viral replication [1].

This is why antivirals are effective during outbreaks. They reduce the severity of symptoms, shorten healing time, and lower viral shedding. Their action is precise and depends entirely on the virus being in an active replicating state.

What changes when herpes enters dormancy

Once herpes moves into sensory nerve cells, its behavior changes completely. During latency, the virus stops producing most of the proteins and enzymes that are needed for replication [2]. Viral DNA polymerase is no longer actively used, and the virus does not attempt to make new copies of itself.

In this dormant state, the virus is biologically quiet. It does not trigger inflammation, it does not alert the immune system, and it does not engage the molecular machinery that antiviral drugs are designed to block.

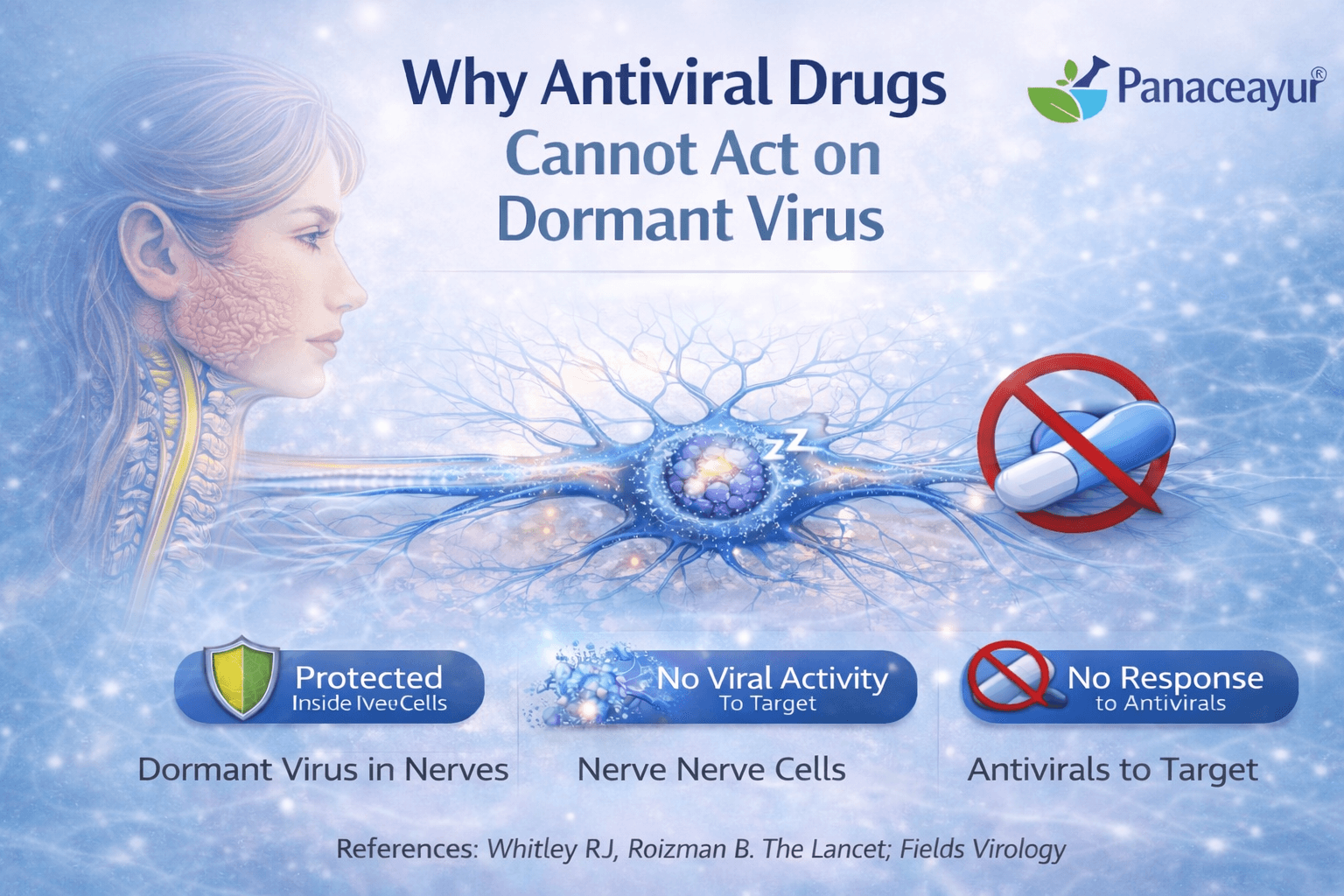

Why dormant virus has no drug target

Because latent herpes virus is not actively replicating, antiviral drugs have no functional target to act upon. The medicines circulate in the body, but the process they are designed to interrupt is simply not happening [1].

Scientific studies confirm that antiviral drugs have no effect on transcriptionally silent viral DNA. The viral genome remains intact inside the nerve cell, but it is inactive and shielded from pharmacological intervention [4].

This explains why even long term or daily antiviral use does not reduce the amount of latent virus stored in nerve tissue.

Why increasing dose or duration does not change the outcome

Many patients in the UK and USA assume that taking antiviral medication for longer periods or at higher doses might eventually eliminate the virus. From a biological perspective, this is not possible with current antiviral drugs.

No matter how long the medicine is taken, it cannot act on a virus that is inactive. The limitation is not related to dosage, treatment adherence, or patient behavior. It is a fundamental mismatch between how the drug works and how latent herpes exists in the body.

Why reactivation occurs after stopping medication

When antiviral medication is stopped, the dormant virus may reactivate under certain conditions such as stress, illness, immune suppression, or hormonal changes. When reactivation occurs, the virus resumes replication, travels back along the nerve, and causes symptoms.

This recurrence does not mean the antiviral drug failed. It means the drug successfully controlled viral activity while it was present, but the underlying dormant virus was never removed [4].

Herpes simplex virus is able to persist in the human body because it establishes latency inside a highly protected part of the nervous system. Modern virology clearly shows that the virus does not hide randomly. Instead, it deliberately settles in sensory nerve ganglia, where both immune attack and drug access are naturally limited. This biological choice allows the virus to survive long term despite treatment and immune responses.

Sensory nerve ganglia as the primary site of herpes latency

After the initial infection on the skin or mucosal surface, herpes simplex virus travels inward along sensory nerve fibers. It reaches sensory nerve ganglia, which are clusters of nerve cell bodies located deep within the body [2]. These ganglia act as relay stations for sensory signals and are directly connected to the areas where herpes symptoms later reappear.

In oral herpes, the trigeminal ganglion is most commonly involved. In genital herpes, the virus typically establishes latency in the sacral ganglia. This pattern is consistent and well documented, confirming that herpes viruses are neurotropic, meaning they are biologically adapted to live inside nerve cells [2]. Once the virus reaches these ganglia, it can remain dormant for many years or even for life.

Immune privilege of nervous tissue

Nervous tissue is essential for survival and normal bodily function. Because nerve cells do not regenerate easily, the body has evolved mechanisms to protect them from excessive immune activity. Scientific research describes this protective state as immune privilege [3].

In immune privileged tissues, immune responses are deliberately restrained. This prevents inflammation that could permanently damage nerve cells. While this protection is vital for preserving neurological function, it also means that infections within nerve tissue are not eliminated as aggressively as they might be in other organs.

Persistence of latent herpes virus within nerve cells

When herpes virus becomes latent inside sensory ganglia, it produces very few viral proteins and remains largely inactive. Because immune surveillance in these areas is reduced, infected nerve cells are not strongly targeted by the immune system [3].

This allows the virus to persist quietly without causing ongoing inflammation or visible symptoms. The persistence of herpes during latency is therefore not due to immune weakness, but rather to normal protective mechanisms that safeguard the nervous system.

Limited access of antiviral drugs to nerve ganglia

In addition to immune privilege, drug delivery to nerve tissue is also restricted. Biological barriers limit how much medication can reach sensory nerve ganglia [3]. Antiviral drugs circulate through the bloodstream, but only small amounts are able to penetrate deeply into nervous tissue.

Even when antiviral medication reaches the ganglia, the virus is inactive and does not engage the processes that these drugs are designed to block. As a result, antiviral therapy has little to no effect on latent virus stored in nerve cells.

Nerve ganglia as long term viral reservoirs

Because of immune privilege, reduced immune surveillance, and limited drug penetration, sensory nerve ganglia function as long term viral reservoirs. Herpes simplex virus can remain dormant within these protected structures and reactivate periodically when conditions such as stress, illness, or immune changes occur [2][3].

This explains why herpes persists despite appropriate medical treatment and why latency remains unchanged under current antiviral therapy models.

Why Daily Suppressive Therapy Does Not Gradually Clear HSV

Daily suppressive antiviral therapy is widely prescribed in the UK and USA for people who experience frequent herpes outbreaks or wish to reduce the risk of transmission. While this approach is effective for symptom control, it does not gradually remove herpes simplex virus from the body. The reason lies in how antiviral drugs work and how herpes persists during latency.

What daily suppressive therapy is designed to achieve

Daily suppressive therapy involves taking antiviral medication every day, even when no symptoms are present. The goal of this approach is to keep viral activity as low as possible. By maintaining a constant level of medication in the body, antiviral drugs can quickly block viral replication if reactivation begins [1].

Clinical studies show that this strategy reduces the frequency and severity of outbreaks and lowers the amount of virus shed from the skin or mucosa during active phases [5]. For many patients, this leads to long symptom free periods and improved quality of life.

However, the purpose of suppressive therapy is control, not elimination.

Why suppressive therapy does not reduce latent viral load

A common assumption among patients is that taking antiviral medicine daily for months or years might slowly weaken or clear the virus. Scientific evidence does not support this idea. Antiviral drugs do not reduce the amount of herpes virus stored in nerve cells during latency [1].

This is because latent herpes virus is inactive. It is not replicating, not producing viral enzymes, and not engaging in the processes that antiviral drugs are designed to block. As a result, the latent viral load inside sensory nerve ganglia remains unchanged, regardless of how long suppressive therapy is continued.

Persistence of viral DNA despite long term treatment

Research has clearly demonstrated that herpes simplex virus DNA remains present in nerve cells even after prolonged antiviral therapy [4]. Long term use of antiviral medication does not remove viral genetic material from sensory ganglia.

This means that suppressive therapy does not weaken the virus over time. It simply prevents active replication while the medication is present. Once the drug is stopped, the latent virus remains fully capable of reactivation under suitable conditions.

Why outbreaks may return after stopping therapy

When daily suppressive therapy is discontinued, some patients experience a return of outbreaks. This does not mean that the treatment failed or that the virus became stronger. It reflects the fact that the underlying latent infection was never removed.

Suppressive therapy acts like a temporary barrier. While the medication is taken, viral activity is controlled. When the barrier is removed, the virus may reactivate if triggered by factors such as stress, illness, immune changes, or hormonal shifts [4].

What suppressive therapy does achieve clinically

Although daily suppressive therapy does not cure herpes, it has clear and proven benefits. Clinical trials show that it significantly reduces outbreak frequency and lowers the risk of transmitting the virus to sexual partners [5].

For this reason, suppressive therapy remains a recommended option in both UK and USA clinical guidelines. Its value lies in symptom management and transmission reduction, not in gradual viral elimination.

Why suppression should not be confused with clearance

It is important to distinguish between suppression and clearance. Suppression means keeping viral activity under control. Clearance would require removing or permanently disabling the virus within nerve cells. Current antiviral drugs are not designed to achieve this level of intervention [1][4].

Understanding this distinction helps patients set realistic expectations. Daily suppressive therapy can provide stability and relief, but it does not gradually clear herpes simplex virus from the body under current medical treatment models [1][4][5].

Many patients in the UK and USA worry that repeated herpes outbreaks mean the virus has become resistant to medication. This concern is understandable, but it is important to clearly separate antiviral resistance from viral latency, as they are very different biological processes.

What antiviral resistance actually means

Antiviral resistance occurs when the herpes virus undergoes genetic changes that reduce the effectiveness of antiviral drugs. In this situation, the virus is actively replicating but the medication is no longer able to block viral DNA replication effectively. True antiviral resistance is usually detected through laboratory testing and is most often seen in people with severely weakened immune systems [6].

In otherwise healthy individuals, antiviral resistance is uncommon. When resistance does occur, it is typically associated with prolonged antiviral exposure in immunocompromised patients, such as those undergoing chemotherapy or organ transplantation [6].

What viral latency means and why it causes recurrence

Viral latency is not a sign of resistance. It is a normal and expected feature of herpes infection. During latency, the virus remains inactive inside nerve cells and is unaffected by antiviral drugs because it is not replicating [6].

When the virus reactivates from latency, outbreaks can occur even if the virus remains fully sensitive to antiviral medication. This reactivation is driven by biological triggers such as stress, illness, immune changes, or hormonal shifts, not by drug failure.

Why recurrence does not mean treatment failure

When herpes symptoms return during or after antiviral therapy, many patients assume the medicine has stopped working. In most cases, this is not true. The medication continues to work as designed during periods of viral replication. The recurrence simply reflects the presence of latent virus that was never removed [6].

Understanding this distinction is important for avoiding unnecessary anxiety and inappropriate changes in treatment.

What Clinical Guidelines Actually Say About Herpes Latency

Clinical guidelines used in the UK and USA provide clear and consistent guidance on how herpes simplex virus behaves in the body and what current treatments can and cannot do. These guidelines are based on decades of clinical research and real world patient outcomes, and they form the basis of standard medical care.

How guidelines describe herpes latency

Authoritative clinical guidance states that herpes simplex virus establishes latency after the initial infection. Once the virus enters sensory nerve cells, it remains there in an inactive state for long periods, often for life [7]. During latency, the virus is not actively replicating and does not cause continuous symptoms, but it is not eliminated from the body.

Guidelines clearly acknowledge that latency is a core biological feature of herpes infection. It is not considered an unusual complication or a sign of inadequate treatment.

What guidelines say about antiviral treatment

Clinical guidelines explain that antiviral medicines are effective for managing active herpes infection. They reduce symptom severity, shorten outbreaks, and lower the risk of transmission when taken correctly [7]. However, they also clearly state that these treatments do not eliminate latent herpes virus from nerve cells.

Antiviral therapy is therefore described as suppressive rather than curative. The medicines control viral activity when the virus reactivates, but they do not remove the virus during latency.

Why herpes is described as incurable in guidelines

When guidelines state that herpes has no cure, they are referring to the absence of an approved medical treatment that can eliminate latent virus from the nervous system [7]. This wording reflects the limits of current pharmacological options, not a lack of understanding of the virus.

Guidelines emphasize that lifelong latency is expected under current treatment models and that recurrence can occur even with proper medical care.

Even though antiviral drugs do not eliminate herpes latency, they remain a central part of herpes management in the UK and USA. This is not due to lack of awareness of their limitations, but because these medicines provide important and measurable clinical benefits within current medical models.

Reduction of transmission risk

One of the main reasons doctors prescribe antiviral therapy is to reduce the risk of transmitting herpes to sexual partners. Clinical studies show that daily antiviral use lowers viral shedding during active and asymptomatic periods, which significantly reduces the chance of passing the virus to others [5].

For many patients, especially those in long term relationships, this benefit is a major factor in treatment decisions. Antiviral therapy allows couples to reduce transmission risk while maintaining normal intimacy under medical guidance.

Control of outbreaks and symptom severity

Antiviral medicines are effective at reducing how often outbreaks occur and how severe they are when they do occur. Suppressive therapy can lead to fewer flare ups, shorter duration of symptoms, and less discomfort [8].

This level of symptom control can significantly improve daily functioning, work attendance, and emotional wellbeing, which is why clinicians continue to recommend these medications despite their inability to cure the infection.

Alignment with current medical treatment models

Modern medical practice in the UK and USA is guided by evidence based outcomes. Antiviral drugs have been shown to provide consistent benefits in controlling herpes infection, even though they do not eliminate latent virus [8].

Within current treatment frameworks, antivirals remain the most reliable option for managing active disease and preventing complications. Doctors prescribe them because they address what is currently achievable, not because they promise complete viral elimination.

Psychological Impact of the Lifelong Virus Message

Being told that herpes is a lifelong infection can have a strong emotional effect on many patients in the UK and USA. Even when physical symptoms are mild or infrequent, the message itself often carries a heavy psychological weight. Clinical research shows that the way herpes is explained and framed can influence mental wellbeing as much as the infection itself [9].

Anxiety linked to uncertainty and recurrence

Many patients experience ongoing anxiety after diagnosis. The uncertainty of when the next outbreak might occur can lead to constant worry and heightened body awareness. Some people become anxious about normal sensations, fearing that any discomfort may signal a recurrence [9].

This anxiety is often increased by the knowledge that the virus remains in the body even when symptoms are absent. The idea of an infection that cannot be fully removed can create a persistent sense of lack of control.

Emotional distress and stigma

Herpes continues to carry social stigma, particularly in sexual relationships. Patients may feel embarrassment, shame, or fear of rejection, even when they understand the medical facts. Studies show that these emotional responses are common and can affect self esteem, confidence, and intimacy [9].

For some individuals, the diagnosis leads to withdrawal from relationships or avoidance of dating due to fear of disclosure. These emotional effects are not caused by the virus itself, but by how the condition is perceived and discussed.

Treatment fatigue and loss of motivation

Long term management with antiviral medication can also lead to treatment fatigue. Taking daily medication without the expectation of cure may cause frustration or emotional exhaustion over time [9]. Some patients report feeling discouraged when outbreaks recur despite consistent treatment.

This fatigue is not a sign of poor coping. It reflects the emotional burden of managing a condition that is described as permanent and requires ongoing attention.

Impact on overall mental wellbeing

Research shows that the lifelong framing of herpes can contribute to low mood, stress, and reduced quality of life in some patients [9]. These psychological effects may persist even when physical symptoms are well controlled.

Understanding the emotional impact of the lifelong virus message is important in clinical care. Clear explanation, reassurance, and realistic framing can help reduce unnecessary distress and support better long term mental wellbeing for people living with herpes.

Understanding the difference between viral suppression and viral eradication is essential for interpreting herpes treatment correctly. These two concepts describe very different biological outcomes, and modern medical literature clearly separates them [10].

What viral suppression means in clinical practice

Viral suppression refers to controlling viral activity so that symptoms are reduced or prevented. In herpes management, suppression is achieved through antiviral medicines that limit viral replication when the virus becomes active. This approach reduces the frequency and severity of outbreaks and lowers viral shedding, which in turn reduces transmission risk [10].

However, suppression does not remove the virus from the body. The herpes virus remains present in a latent form inside sensory nerve cells. Antiviral treatment controls expression of the virus but does not change its underlying presence.

What viral eradication would involve

Viral eradication would mean removing or permanently disabling all viral genetic material from the body. In the case of herpes, this would require addressing the virus within sensory nerve cells where it remains dormant. True eradication would prevent future reactivation because the virus would no longer be biologically viable [10].

This level of intervention is fundamentally different from suppression. It would require approaches capable of influencing latent virus within protected nervous tissue without causing harm to nerve function. Current antiviral drugs are not designed for this purpose.

Why suppression is achievable but eradication is not addressed by current drugs

Modern medicine has developed effective tools for suppressing viral replication because active viral processes are accessible to pharmacological intervention. In contrast, latent viral DNA inside nerve cells is biologically silent and shielded, making eradication a far more complex challenge [10].

This explains why herpes is described as manageable but not curable within current drug based treatment models. Suppression focuses on controlling symptoms and reducing spread, while eradication remains outside the scope of existing antiviral therapies.

Integrative perspectives on eradication beyond suppression

While modern antiviral therapy is centered on suppression, other medical systems approach chronic viral infections from a different conceptual framework. Ayurveda, the traditional medical system of India, interprets herpes as a condition involving long term tissue imbalance, immune dysregulation, and viral persistence within deeper biological pathways. From this perspective, treatment strategies aim to modify the internal environment that supports viral survival rather than focusing solely on symptom control.

Readers who wish to understand how Ayurveda explains viral persistence and proposes long term resolution beyond suppression can explore this detailed article:https://panaceayur.com/can-herpes-be-cured-permanently-real-cure-approach/

This link is provided for educational context and comparative understanding of different medical models, allowing readers to explore how approaches to viral suppression and eradication differ across healthcare systems [10].

Why Research Focus Has Historically Avoided Latency Eradication

Modern herpes research has largely concentrated on controlling viral activity rather than eliminating latent virus. This research direction has not occurred due to lack of awareness or interest, but because of well recognised scientific, ethical, and safety limitations related to how herpes persists within the nervous system.

Risks of immune intervention in nervous tissue

The nervous system is one of the most sensitive and highly protected systems in the human body. Nerve cells do not regenerate easily, and damage to nervous tissue can result in permanent loss of sensation, movement, or autonomic function. Because of this vulnerability, immune activity within nervous tissue is tightly regulated, a phenomenon described as immune privilege [3].

Interventions strong enough to eliminate virus within nerve cells would risk triggering inflammation or immune mediated destruction of healthy neurons. Such outcomes could lead to irreversible neurological damage. This risk has made both clinicians and researchers cautious about pursuing aggressive strategies aimed at eliminating viruses embedded within nerve tissue [3].

Technical challenges in studying latent herpes virus

Latent herpes virus exists in a biologically silent state. During latency, the virus produces minimal proteins and does not actively replicate, making it difficult to detect or measure using conventional laboratory methods [11].

Most antiviral research relies on visible markers such as viral replication, protein expression, or immune activation. Because latent virus does not display these features, researchers face significant challenges in determining whether an experimental intervention has any effect on viral persistence [11].

Ethical limitations in human research

In the UK and USA, medical research must meet strict ethical standards. Experimental treatments must demonstrate a favourable balance between potential benefit and risk. Because herpes infection is generally not life threatening in immunocompetent individuals, exposing patients to therapies that might damage nerve tissue has not met acceptable ethical thresholds [11].

As a result, many proposed latency eradication strategies remain theoretical or limited to laboratory models rather than human trials.

Why suppression became the dominant research focus

Given the risks to nerve tissue, technical barriers to studying latency, and ethical constraints on human experimentation, research efforts have focused on suppression rather than eradication. Suppressing viral replication during active infection is safer, measurable, and clinically useful, making it a practical focus for drug development [3][11].

This focus has shaped the treatments available today, which are effective at controlling outbreaks but do not remove latent virus from the body.

Integrative perspectives on why cure remains unexplored

While modern biomedical research has prioritised suppression due to safety and feasibility concerns, other medical systems approach chronic viral infections from a different conceptual framework. Ayurveda, the traditional medical system of India, interprets herpes as a condition involving long term tissue imbalance, immune dysregulation, and persistence within deeper biological pathways rather than solely as an active viral replication problem.

Readers who wish to explore a detailed comparison of why modern medicine focuses on suppression and how Ayurveda approaches herpes from a root level perspective may find this article informative: https://panaceayur.com/why-modern-medicine-cant-cure-herpes-but-ayurveda-can/

This resource is provided for educational context, allowing readers to understand how different medical systems frame the challenge of viral persistence and why latency eradication has remained largely unexplored within conventional research models [3][11].

Why “No Cure” Persists as the Default Medical Answer

The phrase “no cure” is commonly used by doctors when discussing herpes with patients in the UK and USA. This statement is often misunderstood as meaning that nothing more can be done or that science has reached a final conclusion. In reality, the term reflects biological facts, clinical guidelines, and regulatory definitions rather than a lack of ongoing research or understanding.

Biological persistence of herpes simplex virus

Herpes simplex virus is biologically designed to persist in the human body. After initial infection, the virus establishes latency inside sensory nerve cells, where it remains inactive but intact. Scientific research confirms that this latent viral DNA can persist for life under current medical treatment models [4].

Because the virus remains present inside nerve cells even when symptoms are absent, it cannot be considered eliminated. This biological persistence is a central reason herpes is described as incurable in conventional medicine.

How clinical guidelines use the term “no cure”

Medical guidelines in the UK and USA are written to reflect what current treatments can reliably achieve in clinical practice. These guidelines clearly state that antiviral therapies suppress symptoms and reduce transmission risk, but they do not eliminate latent herpes virus [7].

When clinicians use the phrase “no cure,” they are aligning with this guideline language. The term is intended to set realistic expectations for patients, not to suggest that treatment is ineffective or that improvement is impossible.

Regulatory meaning of “no cure” in medicine

In regulatory terms, a cure is defined as a therapy that has been proven, through controlled clinical trials, to permanently eliminate a disease or its underlying cause. Regulatory agencies require clear and measurable evidence that a treatment removes all disease activity without recurrence [12].

For herpes, no approved drug has demonstrated the ability to eliminate latent viral DNA from nerve cells. As a result, no therapy currently meets the regulatory definition of a cure, even if symptom control is excellent.

Why the term remains standard in clinical communication

Doctors use the term “no cure” because it accurately reflects both biological reality and regulatory standards. It helps ensure that patients understand the limits of current treatments and do not expect antiviral drugs to permanently remove the virus [4][7][12].

This wording does not imply that medical knowledge is complete or that new approaches are impossible. It simply reflects the current state of approved medical therapy.

How This Section Connects to Broader Healing Models

Understanding why antiviral drugs do not eliminate herpes latency naturally leads to a wider discussion about how different medical systems define healing. Modern medicine, regulatory science, and traditional healing systems operate using different therapeutic goals, which shapes how herpes is approached and explained.

Control focused versus resolution focused treatment models

In conventional medical practice in the UK and USA, herpes treatment follows a control focused model. This model aims to suppress viral activity, reduce symptoms, and lower transmission risk. Success is measured by how effectively outbreaks are controlled and how safely patients can manage the condition long term [10].

In contrast, Ayurveda follows a resolution focused model. Rather than viewing herpes only as an external viral problem, Ayurveda understands it as a condition involving long standing imbalance in tissue health, immune regulation, metabolic strength, and internal terrain. From this perspective, the virus persists because the internal environment allows it to survive and reactivate [10].

This difference in therapeutic goals explains why modern medicine emphasizes lifelong management, while Ayurveda aims at long term correction of the underlying biological conditions that support viral persistence.

Why absence of an approved cure does not mean eradication is impossible

Regulatory agencies define a cure based on strict criteria that require measurable elimination of disease through standardized clinical trials. If a therapy does not meet these criteria, it is not classified as a cure, regardless of outcomes in other medical systems [12].

This regulatory definition does not imply that eradication is biologically impossible. It simply reflects the limits of what has been formally approved within modern drug development frameworks. Other medical systems, such as Ayurveda, are not evaluated under the same regulatory pathways and therefore operate with different definitions of healing and recovery [12].

Ayurvedic perspective on viral eradication

Ayurveda approaches herpes by focusing on restoring immune competence, correcting tissue level dysfunction, improving digestive and metabolic strength, and eliminating deep seated pathological factors that allow the virus to remain latent. Rather than directly attacking the virus alone, Ayurvedic protocols aim to change the internal environment so that viral survival and reactivation are no longer supported.

This approach views herpes latency not as an untouchable state, but as a reversible condition when the underlying imbalances are corrected systematically. From an Ayurvedic standpoint, eradication is understood as removal of the biological conditions that sustain viral persistence rather than a single drug based intervention.

Readers who wish to understand in detail how Ayurveda explains herpes latency and outlines a structured approach aimed at viral eradication rather than lifelong suppression can explore this article:https://panaceayur.com/can-herpes-be-cured-permanently-real-cure-approach/

Integrating perspectives without rejecting conventional care

Exploring broader healing models does not require rejecting modern medical care. Antiviral therapy remains valuable for symptom control and transmission reduction. However, understanding different therapeutic paradigms allows patients to make informed decisions and explore complementary approaches when seeking long term resolution [10][12].

This integrative understanding explains why herpes treatment discussions increasingly extend beyond symptom suppression and why patients worldwide continue to explore systems like Ayurveda that aim at addressing the root biological causes of viral persistence rather than managing outbreaks alone.

FAQs

Can antiviral drugs cure herpes permanently

No, antiviral drugs do not cure herpes permanently. They are designed to control the virus during active outbreaks by reducing viral multiplication. Once herpes enters a dormant state inside nerve cells, current antiviral medicines cannot remove it from the body.

Why does herpes come back even after taking antiviral medicine

Herpes comes back because the virus remains inactive inside nerve cells even after treatment. Antiviral medicine works only when the virus is active. When treatment is stopped, the inactive virus can reactivate and cause another outbreak.

Do antiviral drugs kill the herpes virus

Antiviral drugs do not kill the herpes virus completely. They slow down viral activity during outbreaks but do not destroy the virus hidden inside nerve tissue. This is why herpes is described as a long term infection under current medical treatment.

Is long term antiviral therapy safe

Long term antiviral therapy is generally considered safe for many people and is commonly prescribed in the USA and UK. It helps reduce outbreaks and lowers the risk of transmission. However, it does not remove the virus and should be taken under medical guidance.

Does taking antivirals daily reduce herpes over time

Taking antivirals daily can reduce the number and severity of outbreaks, but it does not reduce the amount of inactive virus stored inside nerve cells. The virus remains present even after years of daily treatment.

Why do doctors say there is no cure for herpes

Doctors say there is no cure for herpes because there is currently no approved medicine that can remove the inactive virus from nerve cells. Available treatments focus on controlling symptoms rather than eliminating the virus completely.

Reference

[1] De Clercq, E. (2004)

Antiviral drugs in current clinical use. Journal of Clinical Virology, 30(2), 115–133.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2004.02.009

What this explains:

This paper explains how common antiviral drugs such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir work at a molecular level. These drugs interfere with viral DNA replication, but only when the virus is actively copying itself. If the virus is not replicating, the drug has nothing to block.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

Latent herpes virus does not actively replicate. Therefore, even perfect antiviral drug use cannot affect dormant viral DNA hidden inside nerve cells. This is a design limitation, not a treatment failure.

[2] Steiner, I., Kennedy, P. G. E., & Pachner, A. R. (2007)

The neurotropic herpes viruses: Herpes simplex and varicella-zoster. The Lancet Neurology, 6(11), 1015–1028.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70267-3

What this explains:

This review describes how herpes simplex virus enters the nervous system after initial infection and establishes lifelong latency in sensory nerve ganglia. During latency, the virus remains genetically intact but largely inactive.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

This paper confirms that herpes is fundamentally a neurotropic virus, meaning it survives by hiding inside nerve cells. As long as the virus remains inside neurons, it cannot be removed by standard antiviral drugs.

[3] Carbone, F. R., & Gebhardt, T. (2019)

Immunology of the nervous system. Nature Reviews Immunology, 19(7), 423–435.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0148-y

What this explains:

This paper explains the concept of immune privilege in nervous tissue. The immune system is intentionally less aggressive in the brain and nerve tissues to prevent permanent damage.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

Because nerve tissue is protected from aggressive immune responses, latent viruses inside neurons are also protected. This explains why the immune system itself cannot fully clear herpes once latency is established.

[4] Whitley, R. J., & Roizman, B. (2001)

Herpes simplex viruses. The Lancet, 357(9267), 1513–1518.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04638-9

What this explains:

This authoritative review confirms that herpes simplex virus establishes lifelong latency and that existing antiviral therapies do not eliminate latent viral DNA.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

This paper is frequently cited in clinical guidelines. It clearly states that antiviral therapy controls symptoms but does not cure herpes. This supports why recurrence happens even after long-term treatment.

[5] Corey, L., Wald, A., Patel, R., et al. (2004)

Once-daily valacyclovir to reduce the risk of transmission of genital herpes. New England Journal of Medicine, 350(1), 11–20.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa035144

What this explains:

This clinical trial demonstrates that daily antiviral therapy reduces outbreaks and lowers transmission risk to sexual partners.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

Although suppression improves quality of life and reduces spread, the study confirms that the virus is not eliminated. When treatment stops, viral activity can return because latent virus remains intact.

[6] Piret, J., & Boivin, G. (2011)

Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 55(2), 459–472.

https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00615-10

What this explains:

This paper distinguishes between antiviral drug resistance and viral latency. Resistance occurs when the virus mutates, while latency occurs even when the virus remains fully drug-sensitive.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

Many patients mistakenly believe recurrence means drug resistance. This paper clarifies that most recurrences occur because of latency, not because the drug stopped working.

[7] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021)

Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines: Genital herpes simplex virus.

https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/herpes.htm

What this explains:

These guidelines summarize the official medical consensus. They clearly state that current treatments do not cure herpes and that antiviral therapy is suppressive only.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

This explains why doctors consistently tell patients that herpes is lifelong under current treatment models.

[8] Johnston, C., & Corey, L. (2016)

Current concepts for genital herpes simplex virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(15), 1432–1440.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1506192

What this explains:

This paper outlines how herpes is diagnosed, treated, and managed in modern clinical practice, including why antivirals remain the standard of care.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

It shows that doctors prescribe antivirals not because they cure herpes, but because they reduce symptoms and transmission within current medical limitations.

[9] Mindel, A., & Marks, C. (2005)

Psychological impact of genital herpes. Journal of Health Psychology, 10(3), 403–415.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105305051416

What this explains:

This study documents anxiety, stigma, emotional distress, and treatment fatigue experienced by herpes patients.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

It highlights the human cost of lifelong suppressive therapy without resolution, explaining why many patients continue searching for better answers.

[10] Virgin, H. W., Wherry, E. J., & Ahmed, R. (2009)

Redefining chronic viral infection. Cell, 138(1), 30–50.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.036

What this explains:

This paper explains the difference between controlling a virus and eliminating it. It introduces the concept that chronic infections persist due to host-virus equilibrium.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

It supports the idea that suppressing herpes symptoms is not the same as resolving the infection at a biological level.

[11] Bloom, D. C. (2016)

Alphaherpesvirus latency: A dynamic state of transcription and reactivation. Advances in Virus Research, 94, 1–36.

https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aivir.2015.10.001

What this explains:

This review explains why studying and targeting latent herpes virus is scientifically complex and ethically challenging.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

It clarifies why modern research has focused more on suppression than eradication.

[12] U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2020)

Antiviral drug development and endpoints.

https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-resources/antiviral-drug-development

What this explains:

This document explains how regulatory agencies define “cure” and why most drug approvals focus on measurable symptom reduction.

Why it matters for herpes latency:

It explains why “no cure” often reflects regulatory limitations rather than absolute biological impossibility.

Final Reader Note

Together, these references show that herpes latency persists not because treatment is ineffective, but because current antiviral drugs are not designed to eliminate dormant virus hidden within nerve tissue. Understanding this distinction helps patients interpret medical advice accurately and decide how to approach long-term care.