- What Parkinson’s Disease Is

- Core Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease

- Red Flags That Require Immediate Attention

- Common Disorders Associated With Parkinson’s Disease

- Clinical Implication

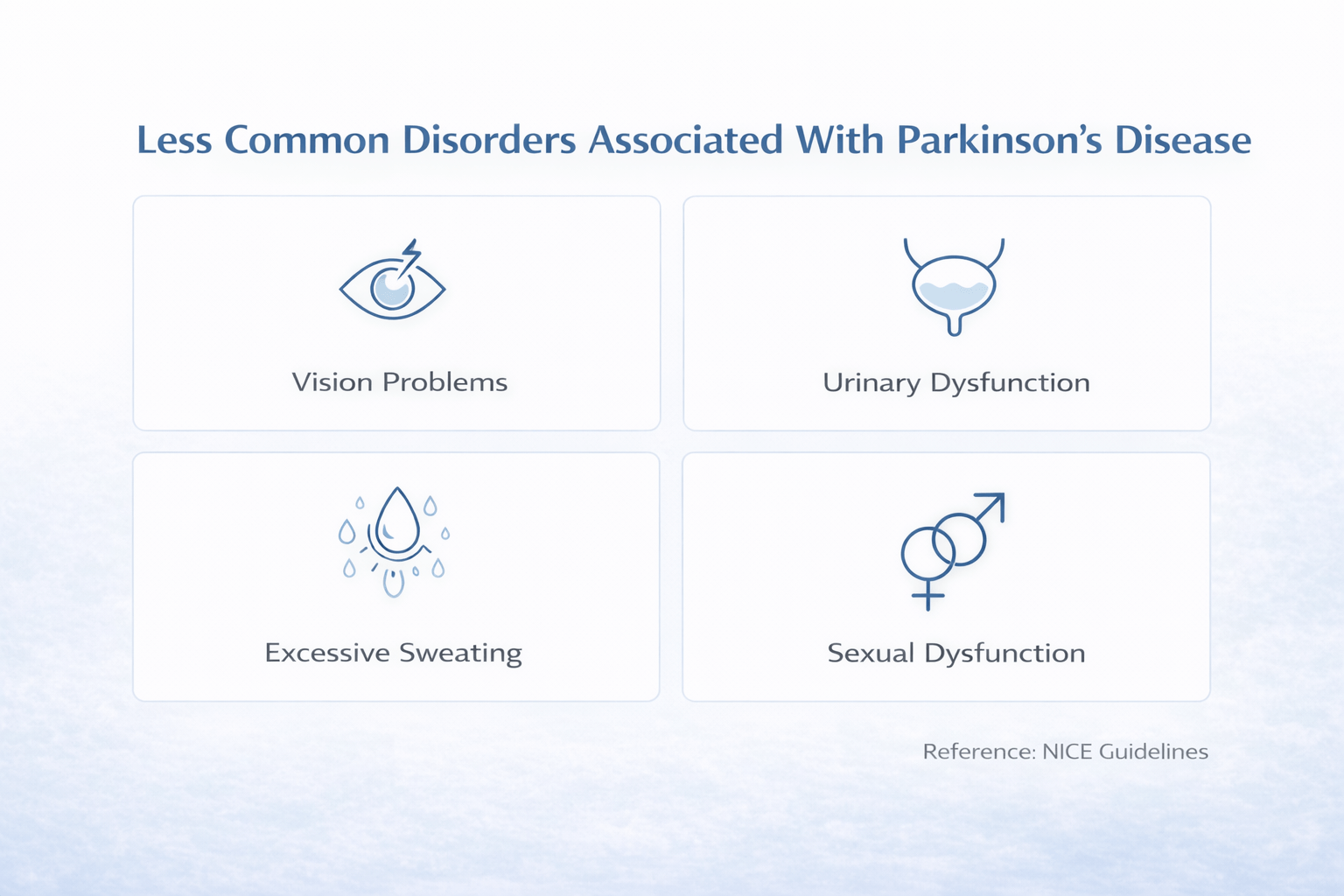

- Less Common Disorders Associated With Parkinson’s Disease

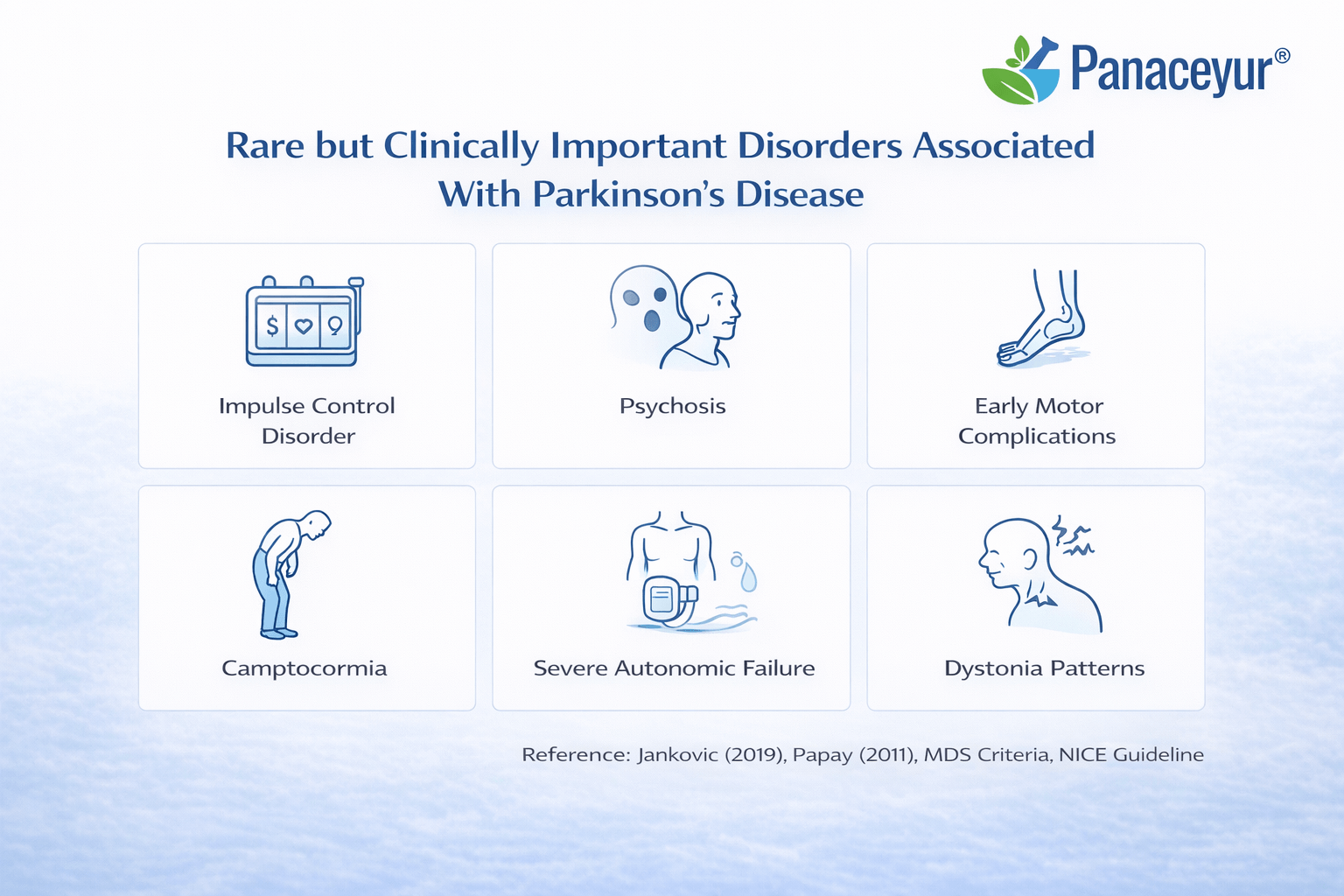

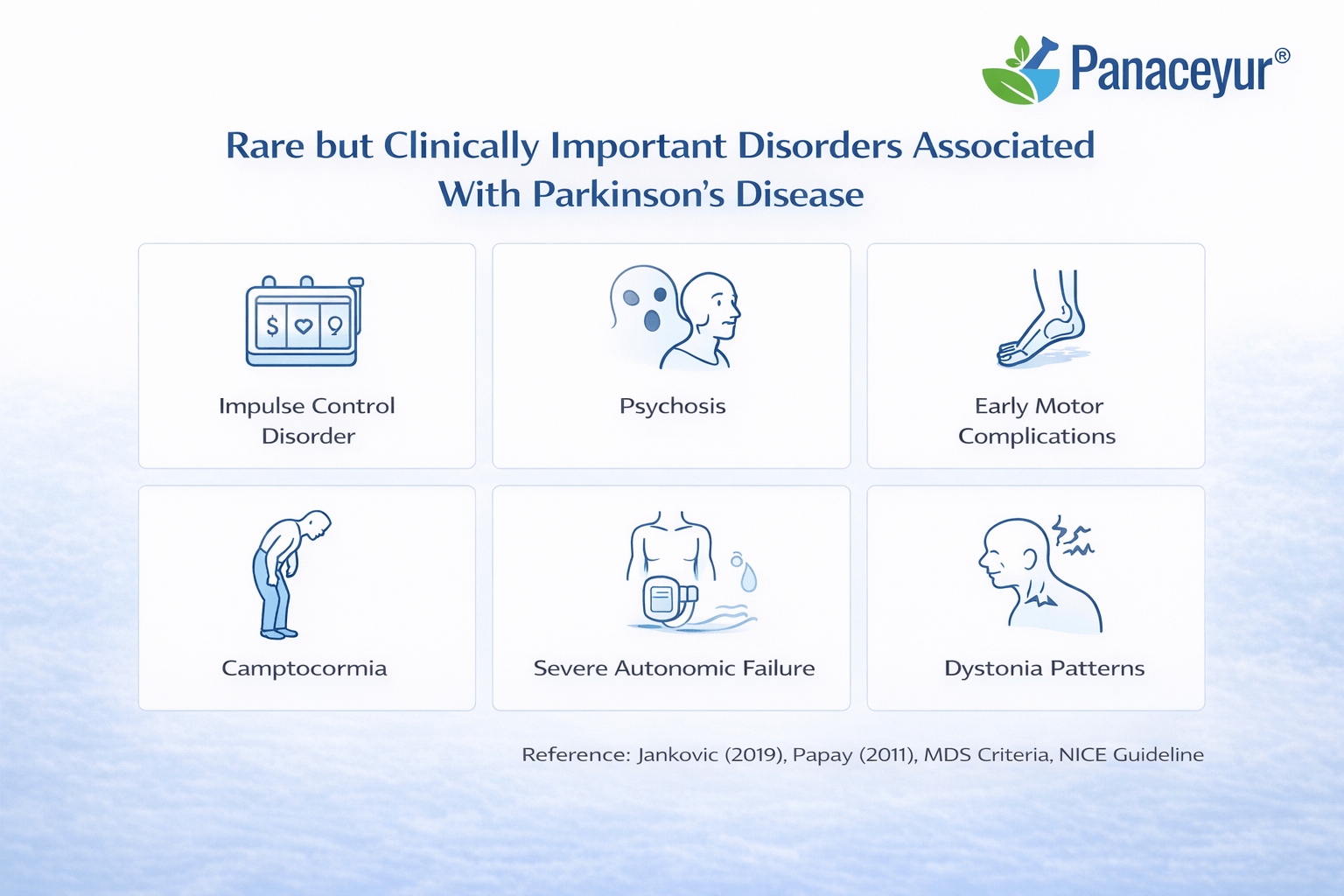

- Rare but Clinically Important Disorders Associated With Parkinson’s Disease

- How Parkinson’s Disease Progresses

- Why Understanding Progression Matters

- Diagnosis in Clinic- What Neurologists Actually Do

- Tests and Imaging in Parkinson’s Disease-When They Help and When They Do Not

- Practical Clinical Perspective

- Conventional Treatment- Medicines, Benefits, and Limits

- Advanced Conventional Therapies: Deep Brain Stimulation and Device-Aided Care

- Exercise, Rehabilitation, Speech and Swallow Therapy- High Impact Evidence

- Risk Factors and Prevention-Focused Lifestyle Framing

- Prodromal Parkinson’s and Early Detection

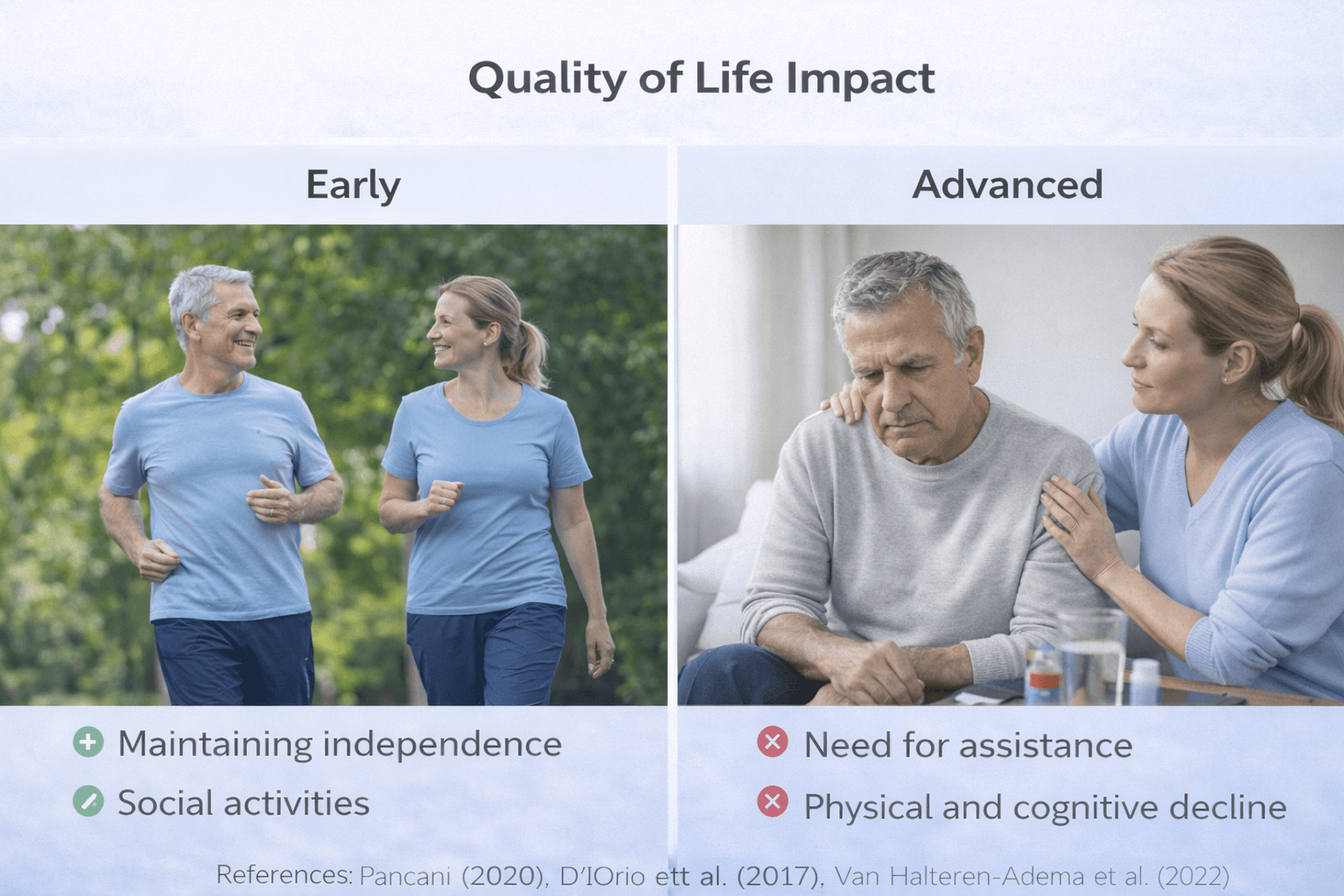

- Prognosis, Life Expectancy Framing, Quality of Life, and Caregiver Reality

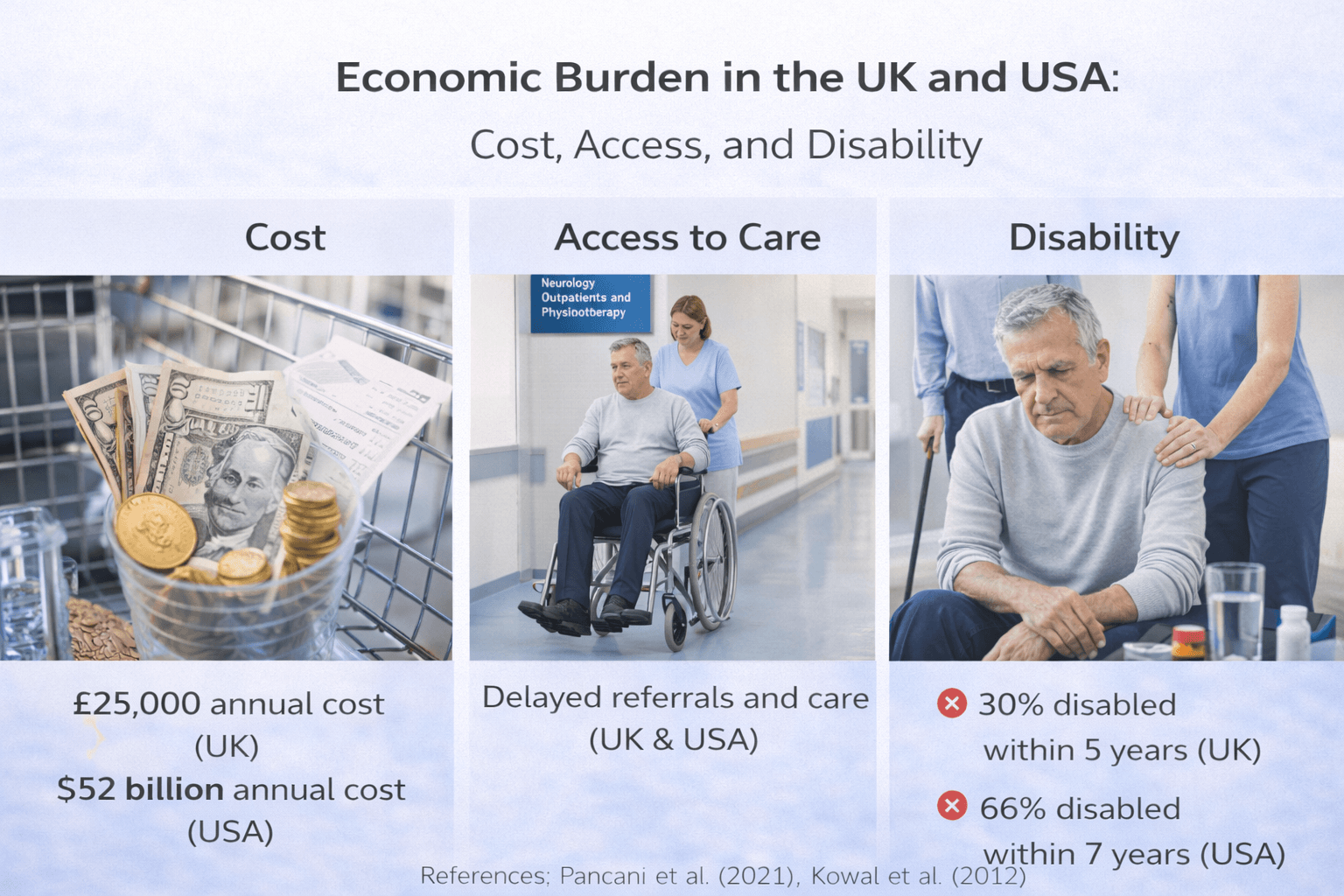

- Economic Burden in the UK and USA- Cost, Access, and Disability

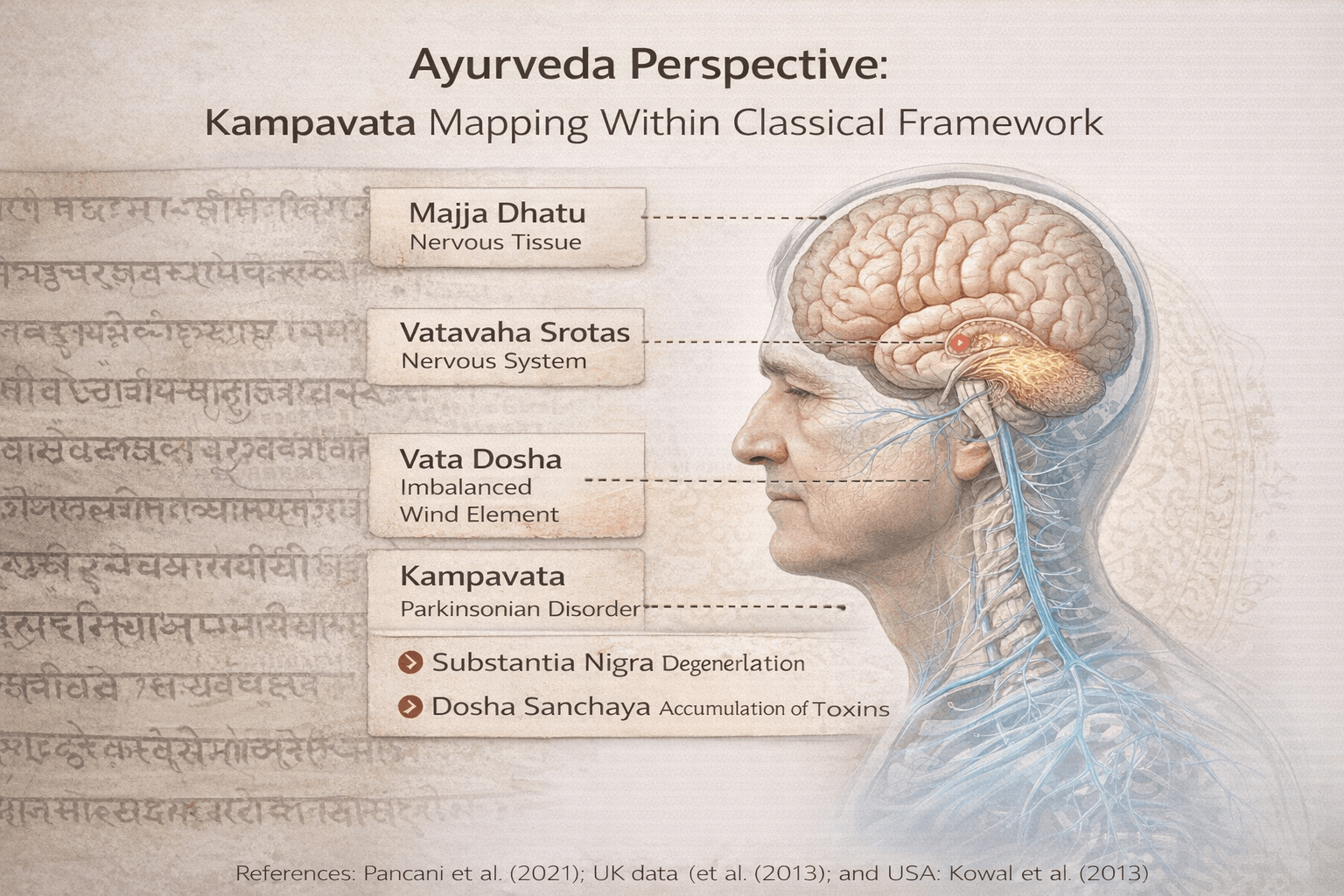

- Ayurveda Perspective: Kampavata Mapping Within Classical Framework

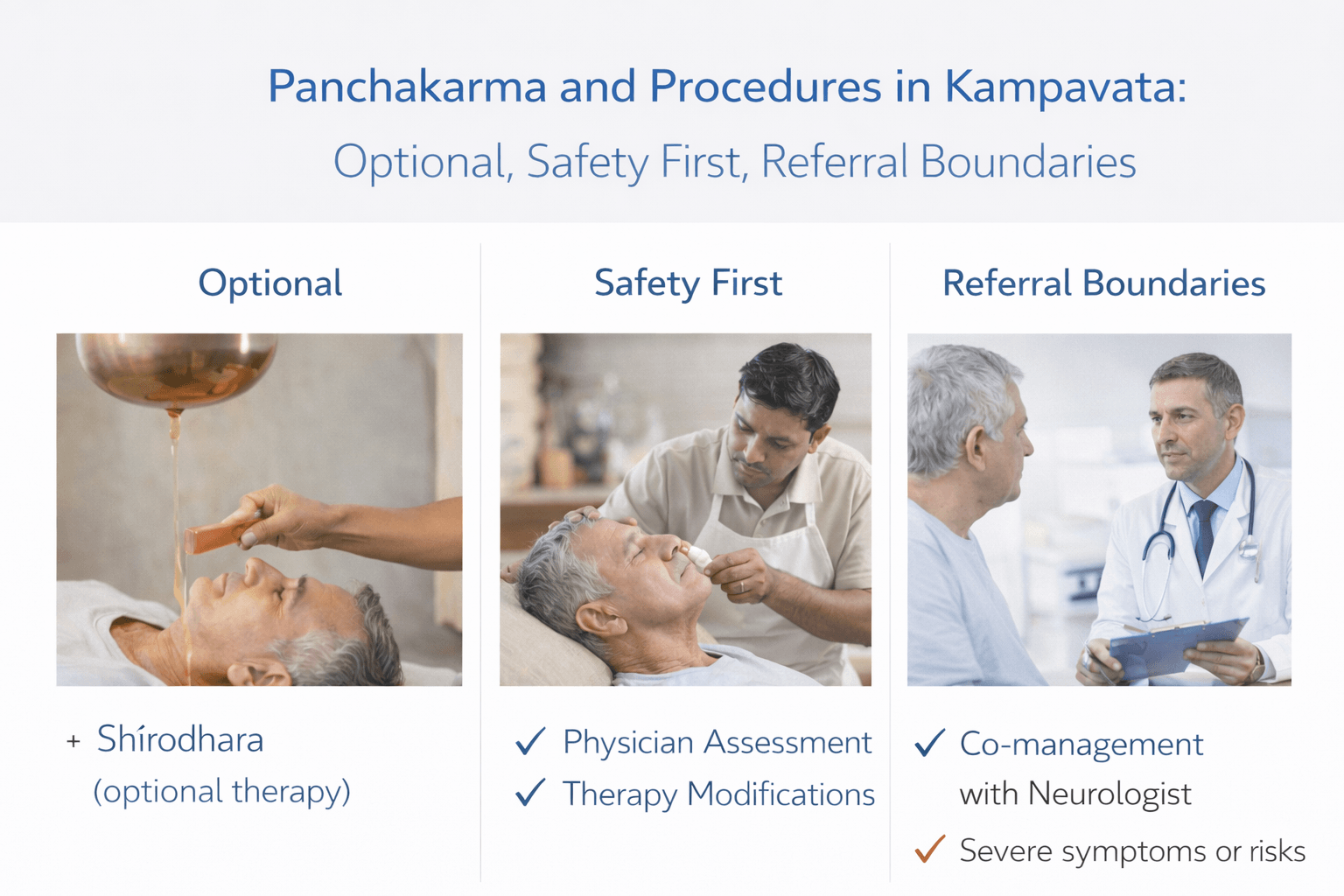

- Panchakarma and Procedures in Kampavata-Optional, Safety First, Referral Boundaries

- Main Avaleha Form Medicine for Cure-Focused

- Preparation Method- Brahma Rasayana Avaleha

- Preparation Method (Patient Friendly)

- Section 2: High Potency Physician-Only Mineral Module

- Critical Warning- Do Not Buy Market Avaleha and Do Not Self Prepare Without an Ayurvedic Doctor

- Safety, Contraindications, Drug– Herb Interaction Cautions, and Medical Supervision

- FAQs

- Reference

Dr. Arjun Kumar is an Ayurvedic physician with over 13 years of clinical experience in neurodegenerative and chronic disorders. He integrates classical Ayurvedic texts with modern neurological research, focusing on evidence-based, root-cause-oriented therapeutic strategies.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurological disorder that primarily affects movement but gradually influences cognition, mood, sleep, and autonomic function. It develops due to degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in a region of the brain called the substantia nigra, leading to impaired motor control and a wide range of non-motor symptoms [18] [15].

Clinically, Parkinson’s disease is characterized by four cardinal motor features: resting tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural instability. However, modern understanding recognizes that Parkinson’s is far more than a movement disorder. Depression, anxiety, constipation, sleep disturbance, and cognitive decline often precede motor symptoms by years, reflecting its multisystem nature [18] [15].

From a therapeutic standpoint, contemporary management focuses on dopamine replacement and symptomatic control. Long-term studies comparing medication strategies demonstrate that while levodopa remains the most effective agent for motor symptom control, it does not halt the underlying neurodegenerative process [23]. This distinction between symptom relief and disease modification is central to understanding both prognosis and the limitations of current conventional treatment.

Globally, Parkinson’s disease represents one of the fastest growing neurological conditions. In the United Kingdom alone, over 145,000 people are currently living with Parkinson’s disease, and prevalence continues to rise due to aging demographics [31]. Similar trends are observed in the United States and worldwide, making Parkinson’s a significant public health concern.

The global impact extends beyond clinical symptoms. Parkinson’s disease affects mobility, independence, employment, and caregiver dynamics. It increases risk of falls, swallowing difficulties, hospitalization, and long-term care needs. As populations age, healthcare systems face increasing economic and social burden related to progressive neurodegenerative disorders.

Understanding Parkinson’s disease early is therefore critical. Early recognition of symptoms, appropriate staging, evidence-based management, and integrative supportive care can significantly improve quality of life and functional outcomes.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Parkinson’s disease, including early signs, causes, progression, associated disorders, modern treatment approaches, prognosis, and an Ayurvedic cure perspective grounded in classical medical texts and contemporary neurological understanding.

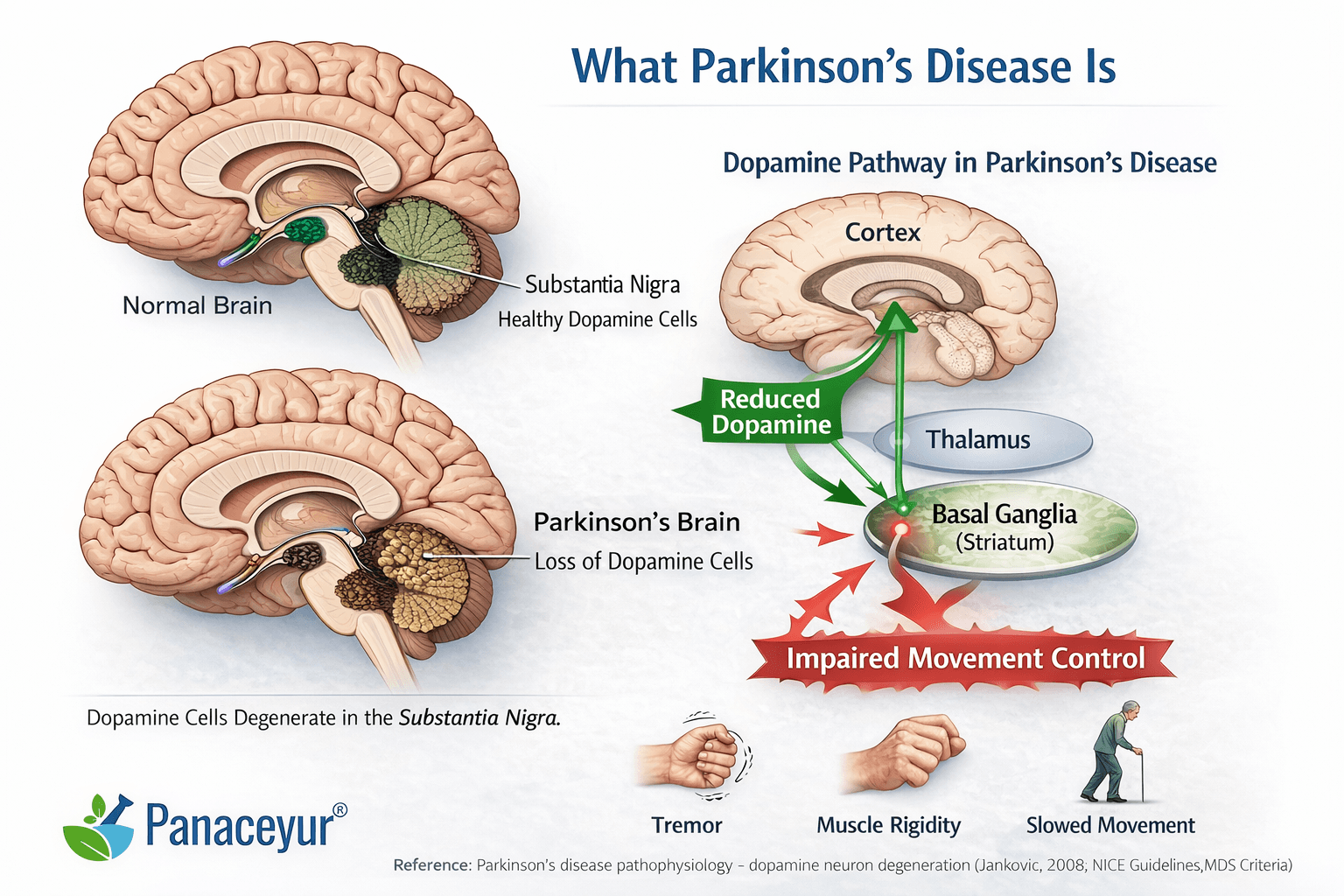

What Parkinson’s Disease Is

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects how the brain controls movement and many automatic body functions. At its core, it develops because certain brain cells responsible for producing dopamine gradually stop working and eventually die [15].

Dopamine is a chemical messenger that allows different parts of the brain to coordinate smooth, controlled movement. When dopamine levels decline, movements become slower, muscles become stiff, and tremors may appear. Over time, additional brain systems can also be affected.

Understanding the basic biology behind Parkinson’s disease helps explain why symptoms change over time and why current treatments improve symptoms but do not fully stop progression.

The Role of Dopamine and the Substantia Nigra

Deep inside the brain lies a small but critical structure called the substantia nigra. This region produces dopamine and sends it to other movement-control centers, especially the basal ganglia. These circuits act like a fine-tuning system for voluntary movement.

In Parkinson’s disease, neurons in the substantia nigra progressively degenerate. As dopamine production decreases, the brain’s movement circuits become imbalanced. This leads to:

• Slowness of movement

• Muscle rigidity

• Resting tremor

• Postural instability

This dopamine deficiency explains many of the hallmark motor symptoms [15].

Protein Changes Inside Brain Cells

Another key feature of Parkinson’s disease involves abnormal accumulation of a protein called alpha-synuclein. In affected neurons, this protein misfolds and clumps together, forming structures known as Lewy bodies.

Research suggests that these protein aggregates interfere with normal cell function and may contribute to neuronal death [6]. While scientists continue to study exactly how this process unfolds, the presence of Lewy bodies is considered a pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease.

How Parkinson’s May Spread Through the Brain

Neuropathological research has proposed that Parkinson’s disease follows a staged pattern of progression within the nervous system. According to this model, early changes may begin in lower brainstem regions and even peripheral nervous structures before advancing to areas responsible for movement control [6].

This helps explain why symptoms such as constipation or loss of smell can appear years before tremor or stiffness develop.

The Gut–Brain Connection

Emerging research has explored the possibility that Parkinson’s disease may involve interactions between the digestive system and the brain. The vagus nerve connects the gut to the brainstem, and some studies suggest that pathological processes involving alpha-synuclein may be present in the gastrointestinal system in early stages [28].

While this area of research is ongoing, it provides a possible explanation for early non-motor symptoms like chronic constipation and gastrointestinal discomfort.

Why Treatment Improves Symptoms but Not the Underlying Process

Modern treatment strategies, particularly levodopa and other dopaminergic medications, work by restoring or mimicking dopamine activity in the brain. Long-term comparative studies show that these treatments significantly improve motor symptoms, especially in early and moderate stages [23].

However, these medications do not reverse neuronal loss or stop alpha-synuclein accumulation. They improve the brain’s chemical signaling but do not eliminate the underlying degenerative process.

In simple terms, Parkinson’s disease occurs because specific brain cells gradually deteriorate, leading to dopamine deficiency and disruption of coordinated movement. Current therapies address the chemical imbalance, while research continues to explore strategies aimed at slowing or modifying disease progression.

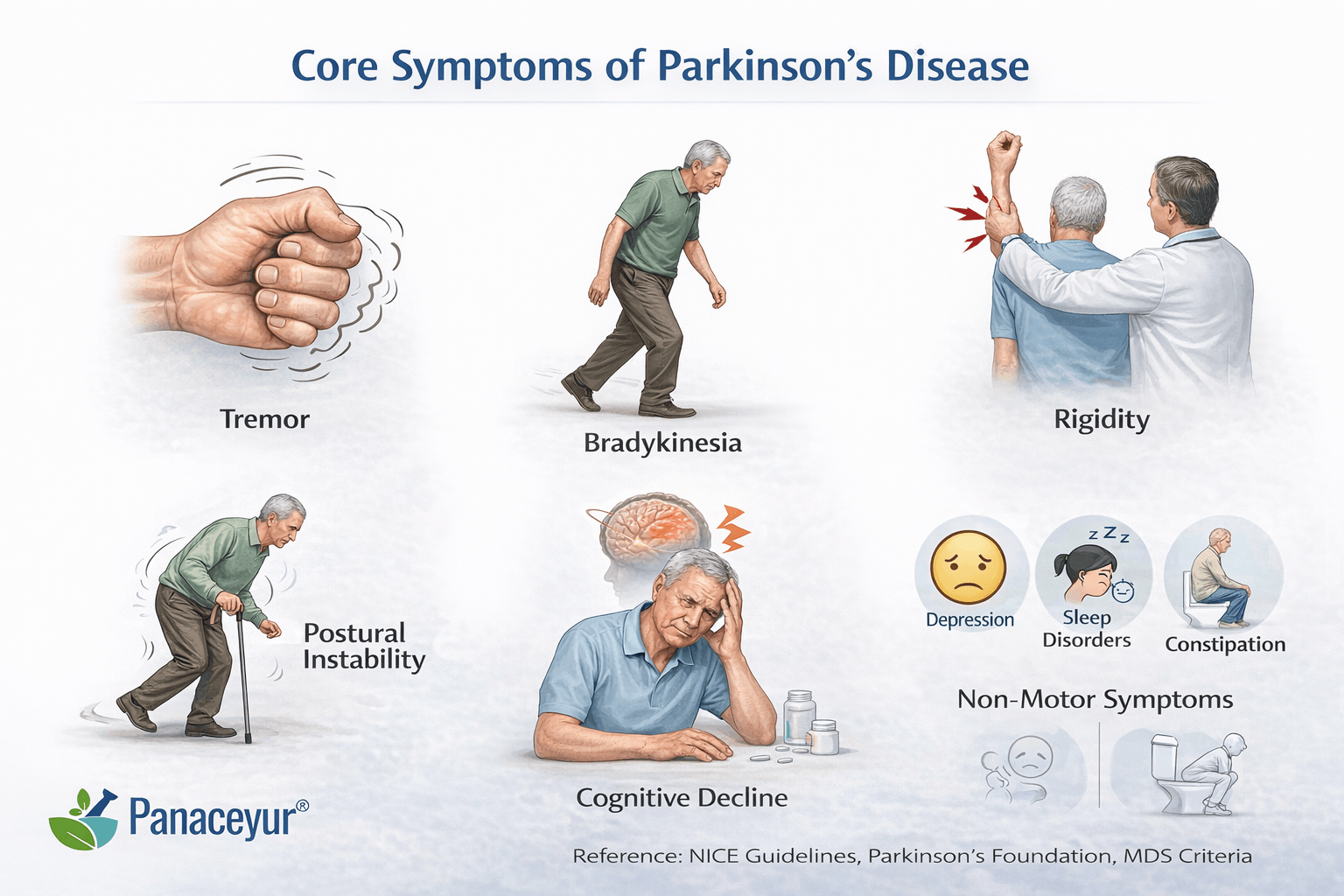

Core Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease presents with a complex combination of motor and non-motor features that evolve over time. Although the condition is often recognized by tremor, its full clinical spectrum extends far beyond visible movement abnormalities. Understanding both motor and non-motor symptoms is essential for early detection, accurate staging, and appropriate long-term management [15] [18].

Modern clinical guidelines emphasize that Parkinson’s disease should be viewed as a multisystem neurological disorder rather than purely a movement disorder [11]. Some symptoms are subtle in the beginning and may be overlooked for years before formal diagnosis.

Motor Symptoms

Motor symptoms are the most recognizable features of Parkinson’s disease and are typically required for clinical diagnosis. These arise primarily due to dopamine deficiency in the basal ganglia circuitry [15].

Bradykinesia

Bradykinesia, or slowness of movement, is the most essential motor feature. It manifests as reduced spontaneous movement, delayed initiation, and progressive decrease in movement amplitude during repetitive actions. Patients may notice difficulty buttoning clothes, typing, or turning in bed. Facial expression may become reduced, producing what is often described as masked facies.

Clinically, bradykinesia distinguishes Parkinson’s disease from isolated tremor disorders. It is central to diagnosis and reflects dysfunction in dopamine-dependent motor circuits [15] [11].

Resting Tremor

A classic resting tremor often begins asymmetrically, typically affecting one hand. It is most noticeable when the limb is relaxed and decreases with voluntary movement. Although tremor is common, it is not universal. Some patients present with rigidity-dominant or akinetic forms without significant tremor [18].

Importantly, tremor alone does not confirm Parkinson’s disease. When tremor occurs without bradykinesia, alternative diagnoses such as essential tremor should be considered.

Rigidity

Rigidity refers to increased muscle tone and resistance to passive movement. It may feel like stiffness in the neck, shoulders, or limbs. On examination, clinicians may detect cogwheel rigidity, a ratcheting sensation during joint movement.

Rigidity contributes to discomfort, reduced arm swing while walking, and postural abnormalities. Over time, it can increase fall risk and musculoskeletal strain [15].

Postural Instability

Postural instability usually develops in later stages. Patients may experience imbalance, shortened stride, and difficulty turning. Freezing of gait, a sudden inability to initiate movement, can also occur in more advanced disease.

Falls represent a major source of morbidity and hospitalization in Parkinson’s disease, particularly in older adults [18].

Non-Motor Symptoms

Non-motor symptoms often precede motor signs and may significantly affect quality of life. These symptoms reflect widespread neurochemical and autonomic involvement beyond the motor system [11].

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

Depression and anxiety are common and may appear years before motor onset. These are not simply psychological reactions to diagnosis but are considered part of the disease process. Cognitive slowing and executive dysfunction may develop, and some patients progress to Parkinson’s disease dementia in later stages [15] [18].

Hallucinations can occur, particularly in advanced disease or as medication side effects, requiring careful monitoring [11].

Sleep Disturbances

Sleep disorders are frequent and multifactorial. REM sleep behavior disorder may precede diagnosis, while insomnia, fragmented sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness are common during established disease. Sleep impairment significantly affects daytime functioning and caregiver burden [18].

Autonomic Dysfunction

Autonomic symptoms include constipation, orthostatic hypotension, urinary urgency, and sexual dysfunction. These features reflect involvement of autonomic pathways and are often underreported unless specifically queried [11].

Chronic constipation may appear years before motor symptoms and is increasingly recognized as an early warning feature [15].

Pain and Sensory Changes

Musculoskeletal pain, shoulder stiffness, and generalized discomfort are frequently reported. Sensory complaints may be misattributed to orthopedic causes when they are, in fact, part of the disease spectrum [18].

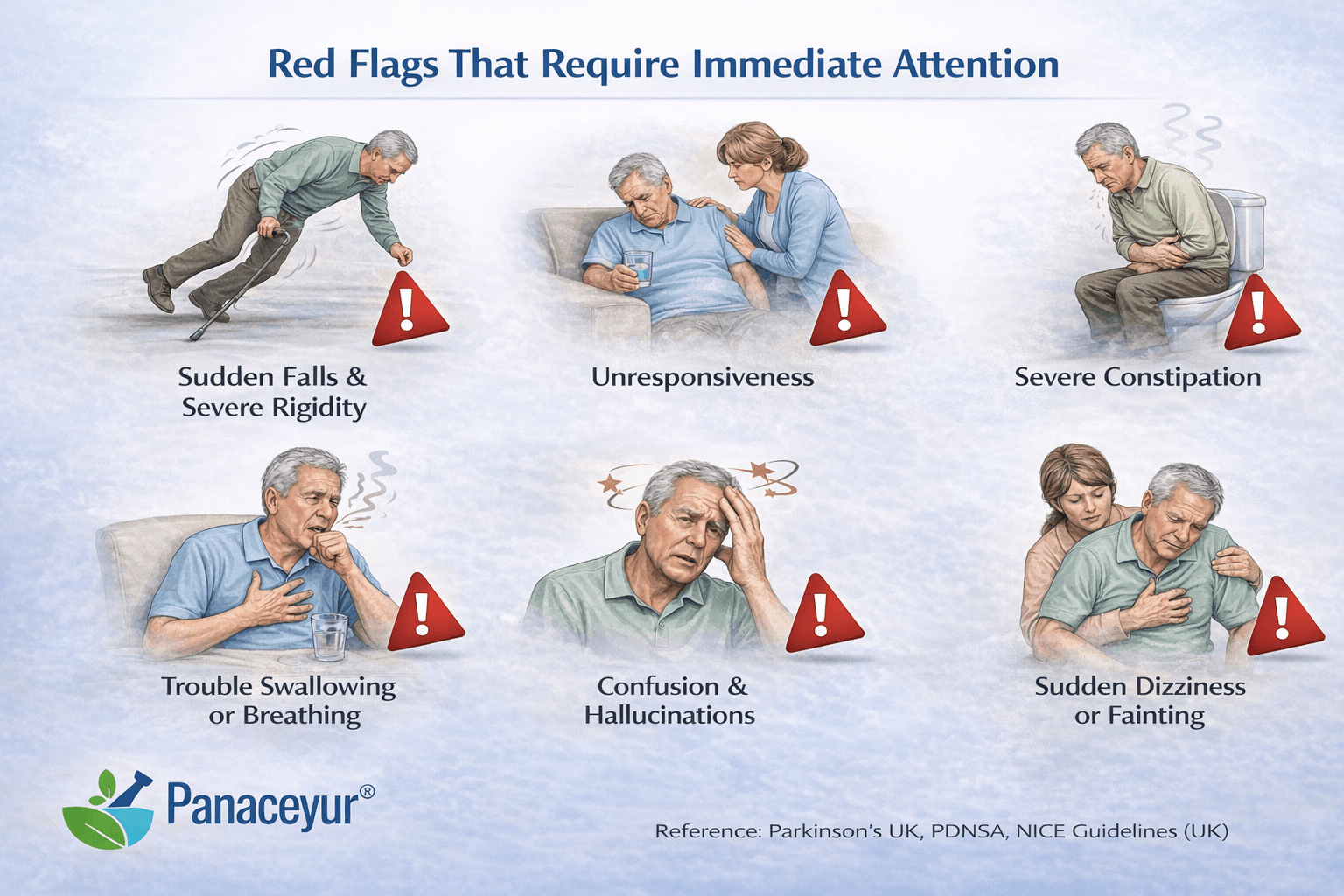

Red Flags That Require Immediate Attention

While Parkinson’s disease typically progresses gradually, certain features warrant urgent evaluation.

Rapid Symptom Progression

If symptoms worsen unusually quickly, alternative diagnoses such as atypical parkinsonian syndromes should be considered. Conditions like multiple system atrophy or progressive supranuclear palsy may progress more aggressively than idiopathic Parkinson’s disease [11].

Early Severe Autonomic Failure

Profound blood pressure drops, severe urinary retention, or early swallowing difficulty may indicate atypical variants rather than classic Parkinson’s disease [18].

Poor Response to Levodopa

Most patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease demonstrate improvement with dopaminergic therapy. A poor or absent response should prompt re-evaluation of diagnosis [23].

Early Frequent Falls

Falls occurring within the first year of symptom onset are uncommon in typical Parkinson’s disease and may signal an alternative neurodegenerative condition [11].

Prominent Early Cognitive Decline

Severe early dementia or visual hallucinations at presentation may suggest dementia with Lewy bodies rather than classic Parkinson’s disease [18].

In summary, Parkinson’s disease encompasses both motor and non-motor features that reflect widespread neurodegeneration. Recognizing early patterns, understanding red flags, and distinguishing typical progression from atypical presentations are essential for accurate diagnosis and optimal management [15] [23].

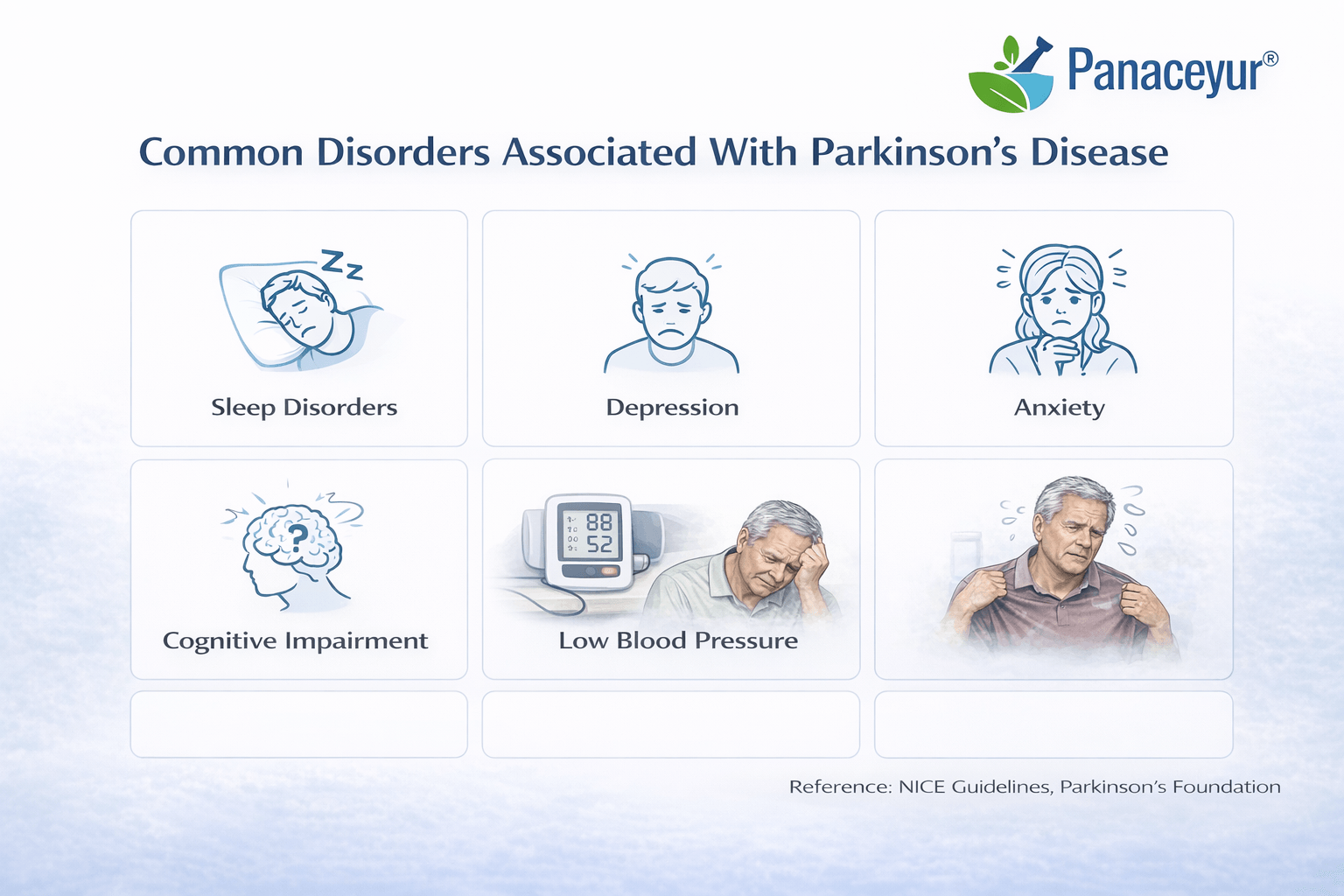

Common Disorders Associated With Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease extends far beyond tremor and slowness of movement. In contemporary neurology, it is understood as a multisystem disorder affecting motor, autonomic, cognitive, psychiatric, and sensory pathways [15] [18].

These associated conditions often contribute more to disability and reduced quality of life than motor symptoms alone. Modern management guidelines emphasize systematic screening for non-motor symptoms as a core component of care [11].

Gastrointestinal Dysfunction

Chronic constipation is one of the most prevalent associated disorders. It may precede motor symptoms by years and reflects early autonomic and enteric nervous system involvement. Slowed colonic transit can interfere with medication absorption, particularly levodopa, affecting motor stability [23].

In advanced stages, delayed gastric emptying and weight loss may develop, increasing nutritional vulnerability.

Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Depression and anxiety are highly prevalent and often under-recognized. These symptoms arise not only as psychological responses but also due to neurochemical alterations involving dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways [15].

Apathy, distinct from depression, is also common and characterized by reduced initiative and emotional engagement. It may impair adherence to exercise and rehabilitation plans.

Mild cognitive impairment frequently develops during the disease course. Executive dysfunction, slowed thinking, and impaired attention may progress to Parkinson’s disease dementia in later stages [18].

Sleep Disorders

Sleep fragmentation, insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness, and REM sleep behavior disorder are frequent. Sleep disturbances significantly affect cognition, mood, and caregiver burden [11].

REM sleep behavior disorder is particularly relevant because it may appear years before motor onset and is strongly associated with synucleinopathies [18].

Autonomic Dysfunction

Autonomic impairment is a defining non-motor feature.

Orthostatic hypotension can cause dizziness and falls due to impaired blood pressure regulation [11].

Urinary dysfunction, including urgency and nocturia, is common and may disrupt sleep patterns.

Sexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction in men and reduced libido in both sexes, reflects autonomic and dopaminergic pathway disruption [15].

Swallowing and Salivary Disorders

Dysphagia emerges gradually as bradykinesia affects oropharyngeal muscles. It increases aspiration risk and contributes to hospitalization in advanced disease [18].

Sialorrhea, or excessive drooling, results from impaired swallowing rather than excess saliva production.

Sensory and Dermatologic Manifestations

Hyposmia, or reduced sense of smell, often precedes motor diagnosis and may serve as an early clinical clue [15].

Seborrheic dermatitis is also frequently observed and may be related to autonomic dysfunction.

Pain and Musculoskeletal Disorders

Pain syndromes may be musculoskeletal, neuropathic, or central in origin. Shoulder pain and rigidity may be mistaken for orthopedic disorders in early stages.

Rigidity and altered posture increase mechanical strain, contributing to chronic discomfort [18].

Fatigue and Reduced Stamina

Fatigue remains one of the most disabling and poorly understood symptoms. It may persist even when motor symptoms are optimally managed. Neurochemical imbalance, sleep disruption, and mood disturbance all contribute [15].

Clinical Implication

These associated disorders are not secondary complications but intrinsic components of Parkinson’s disease. Long-term treatment studies show that dopaminergic medications primarily address motor symptoms, while non-motor symptoms often require additional targeted management strategies [23].

Early recognition and structured intervention significantly reduce hospitalization, caregiver strain, and decline in independence [11] [18].

Less Common Disorders Associated With Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease can progress in ways that are not obvious from tremor and slowness alone. A subset of patients develop less common complications involving behavior, perception, posture, and treatment-related motor fluctuations. These problems often determine real-world disability, caregiver stress, and safety risk more than classic motor signs. UK and USA standards recommend proactive screening for these complications, especially in patients receiving dopamine agonists or those describing unpredictable symptom changes [10] [11].

Impulse Control Disorders and Related Behavioral Syndromes

Impulse control disorders are clinically important complications most often linked to dopamine agonists and, less commonly, other dopaminergic therapies. They include pathological gambling, compulsive buying, binge eating, and hypersexual behavior. Many patients conceal symptoms due to shame, and family members may notice first.

Two related syndromes should be recognized because they change management. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome involves compulsive overuse of dopaminergic medication beyond prescribed doses, driven by reward circuitry effects. Punding refers to repetitive, purposeless behaviors such as sorting, dismantling, or excessive hobby-like activity that becomes compulsive. These behaviors can devastate finances and relationships and are preventable when clinicians routinely screen at each follow-up and adjust medications early [10] [11].

Psychosis and Hallucinations in Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease psychosis is a major clinical turning point. It often begins with minor phenomena such as illusions, a sense of presence, or visual misperceptions, and can progress to formed visual hallucinations and delusional beliefs. Psychosis may reflect disease progression, but it is frequently worsened by dopaminergic medication burden.

Management requires careful, stepwise medication review rather than abrupt withdrawal, because sudden reduction can trigger severe motor deterioration and medical instability. National guidance emphasizes structured assessment to protect both safety and motor function [10] [11].

Severe Autonomic Failure Patterns and Why They Matter

Autonomic symptoms are common in Parkinson’s disease, but severe patterns are less common and clinically significant. These include marked orthostatic hypotension with syncope, profound constipation with severe gastrointestinal dysmotility, and major urinary retention.

When severe autonomic failure appears early, progresses rapidly, or dominates the clinical picture, reassessment is essential because it may suggest atypical parkinsonism rather than typical Parkinson’s disease. UK guidance highlights that early severe autonomic impairment should trigger diagnostic caution and specialist-level evaluation [10] [11].

Dystonia Patterns in Parkinson’s Disease

Dystonia refers to sustained or intermittent muscle contractions that cause abnormal postures and pain. In Parkinson’s disease, it commonly appears as early morning foot dystonia, toe curling, calf cramping, or painful inversion of the foot. Cervical dystonia and jaw or facial dystonia can also occur in some patients.

Dystonia often tracks dopamine fluctuations. Off-period dystonia tends to occur when medication levels are low, while peak-dose dystonia can occur when medication levels are high. Correctly identifying the pattern is critical because timing adjustments may relieve dystonia dramatically without adding new drugs [11].

Medication-Related Motor Complications That Can Appear Earlier Than Expected

Levodopa remains the most effective therapy for motor symptom control, but long-term dopaminergic treatment can lead to motor complications. These may occur earlier in some patients depending on age, dose, disease severity, and individual sensitivity. Common motor complications include wearing-off, where benefit shortens before the next dose, and on-off fluctuations, where mobility changes unpredictably. Dyskinesias also occur and should be classified because management differs. Peak-dose dyskinesia occurs at maximal medication effect, diphasic dyskinesia occurs as medication levels rise or fall, and off-period dyskinesia is less common but clinically significant.

These complications reflect changes in dopamine receptor responsiveness over time rather than sudden acceleration of neurodegeneration. UK and international treatment guidance emphasizes individualized medication strategy to balance function and long-term complications [10] [25].

Camptocormia and Axial Postural Deformities

Camptocormia is an abnormal forward flexion of the trunk that worsens in standing and walking and improves when lying down. Although less common than tremor or rigidity, it is clinically serious because it increases fall risk, restricts walking distance, intensifies back pain, and can impair breathing in advanced cases.

Camptocormia may reflect axial dystonia, severe rigidity, or paraspinal muscle dysfunction. It often requires multidisciplinary management involving physiotherapy, posture retraining, and careful medication review. Early recognition matters because prolonged deformity can become structurally fixed and harder to reverse functionally [11].

Why These Less Common Disorders Change Outcomes

These complications are not “side issues.” They often determine whether a person can remain independent, maintain relationships, continue work, and stay safe at home. UK and USA-aligned guidance supports routine screening for impulse control disorder, hallucinations, autonomic collapse, dystonia patterns, early motor fluctuations, and postural deformities as part of ongoing Parkinson’s care [10] [11]. UK prevalence data underscores that while not every patient develops these features, they are common enough to justify structured screening across the patient population rather than only reacting after crises occur [17].

Rare but Clinically Important Disorders Associated With Parkinson’s Disease

While most individuals with Parkinson’s disease experience a relatively predictable combination of motor and common non-motor symptoms, a smaller subset develop rare but clinically significant complications. These conditions often mark a shift in disease trajectory, increase morbidity, and require specialist-level management. Early recognition is essential because outcomes depend heavily on timing of intervention and diagnostic clarity [12] [20].

Parkinson’s Disease Dementia Trajectory

Cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease typically follows a gradual trajectory. Many patients first develop mild cognitive impairment characterized by executive dysfunction, slowed processing speed, impaired attention, and difficulty multitasking. Over time, some progress to Parkinson’s disease dementia, defined by significant cognitive impairment that interferes with daily function [12].

The transition is not abrupt. It reflects progressive cortical involvement beyond the dopaminergic motor circuits. Visuospatial dysfunction, impaired judgment, and fluctuating attention are common features. Hallucinations may emerge during this phase, especially in advanced stages or under high dopaminergic load.

The trajectory is clinically important because dementia significantly alters prognosis, increases caregiver burden, and raises the risk of institutional care. Early cognitive screening and longitudinal monitoring are therefore essential in routine Parkinson’s management [20].

Dementia With Lewy Bodies Overlap

Distinguishing Parkinson’s disease dementia from dementia with Lewy bodies is crucial but often complex. Both conditions share alpha-synuclein pathology and overlapping clinical features. The key distinction lies in timing.

If dementia develops after well-established motor Parkinson’s disease, the diagnosis remains Parkinson’s disease dementia. If cognitive impairment either precedes or occurs within one year of motor symptoms, dementia with Lewy bodies should be considered [7].

Dementia with Lewy bodies often presents with early visual hallucinations, cognitive fluctuations, and pronounced sensitivity to antipsychotic medications. Misclassification can lead to inappropriate treatment choices and adverse outcomes. Therefore, accurate temporal assessment is clinically critical [12].

Atypical Parkinsonism Differentials

When certain features appear unusually early or progress rapidly, clinicians must consider atypical parkinsonian syndromes rather than idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. These include multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration [22].

Red flags suggesting atypical pathology include:

• Early severe autonomic failure

• Early frequent falls

• Prominent early cognitive decline

• Poor response to levodopa

• Rapid progression of disability

Atypical parkinsonism often carries a different prognosis and may require alternative management strategies. Accurate differentiation is essential because long-term expectations, complication risks, and treatment responses differ significantly from classic Parkinson’s disease [22] [20].

Severe REM Sleep Behaviour Disorder and Conversion Risk

REM sleep behaviour disorder is characterized by loss of normal muscle atonia during REM sleep, leading to dream enactment behaviors such as shouting, punching, or falling from bed. While it can occur in established Parkinson’s disease, severe REM sleep behaviour disorder may precede motor diagnosis by years [16].

Longitudinal research indicates that individuals with idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder have a significantly increased risk of converting to a synucleinopathy, including Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies over time [16] [12].

This conversion risk framing is clinically important. REM sleep behaviour disorder is not merely a sleep disturbance but a potential early biomarker of neurodegeneration. Early identification allows closer neurological monitoring and early intervention planning.

Advanced Swallowing Complications

Swallowing difficulty is common in Parkinson’s disease, but advanced dysphagia represents a rare yet serious complication. As bulbar motor coordination deteriorates, patients may develop silent aspiration, recurrent pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration [20].

Advanced swallowing impairment often emerges in later stages and is associated with increased hospitalization and mortality risk. Objective swallow assessment, speech therapy referral, and dietary modification become critical at this stage.

Aspiration pneumonia remains one of the most serious complications in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Proactive screening significantly reduces risk and improves survival outcomes [12].

Why These Rare Complications Matter

These rare but clinically important disorders signal deeper cortical involvement, atypical pathology, or advanced disease progression. They alter prognosis, increase caregiver dependency, and often require specialist multidisciplinary care.

Clinical frameworks emphasize structured monitoring for cognitive decline, autonomic instability, severe sleep disorders, and swallowing dysfunction throughout the disease course [20] [22].

Recognizing these patterns early enables safer medication management, appropriate referral, and realistic care planning.

How Parkinson’s Disease Progresses

Parkinson’s disease progresses through a combination of gradual neurodegeneration, adaptive brain changes, and treatment-related motor fluctuations. Progression is not purely linear. Instead, it reflects evolving involvement of motor circuits, autonomic pathways, limbic structures, and cortical networks. Understanding how Parkinson’s advances requires attention to both biological staging and functional tracking [6].

Biological Progression and Network Spread

Neuropathological models suggest that Parkinson’s disease may begin in lower brainstem regions or peripheral autonomic structures before advancing to the substantia nigra and eventually cortical areas [6]. This helps explain why non-motor symptoms such as constipation, hyposmia, and REM sleep behaviour disorder can precede classic motor signs by years.

As neuronal loss in the substantia nigra reaches a critical threshold, dopamine deficiency becomes clinically visible through bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor. Later cortical involvement contributes to cognitive decline and behavioral changes.

Prodromal Phase

The prodromal stage refers to the period before motor diagnosis. During this phase, individuals may experience subtle non-motor features such as chronic constipation, depression, anxiety, reduced sense of smell, or REM sleep behaviour disorder.

Although not every individual with these symptoms develops Parkinson’s disease, longitudinal research suggests that certain combinations increase conversion risk [6]. Recognition of this phase is increasingly important for early monitoring and research-based intervention strategies.

Early Motor Stage

Once motor symptoms emerge, Parkinson’s disease is typically unilateral or asymmetric. Patients may notice mild tremor, reduced arm swing, stiffness, or slowed movement. Balance is generally preserved.

According to the Hoehn and Yahr staging system, early disease corresponds to stage 1 or early stage 2, characterized by unilateral or mild bilateral involvement without postural instability [5].

Medication response during this phase is usually strong and predictable.

Bilateral Stage With Emerging Instability

As degeneration progresses, motor symptoms become bilateral. Subtle balance impairment may begin, particularly during turning or rapid directional changes.

Stage 3 of the Hoehn and Yahr scale marks the onset of postural instability while maintaining physical independence [5]. Falls may start to occur in some individuals.

At this point, disease progression becomes more functionally apparent. Patients may require adjustments in work duties or lifestyle modifications.

Advanced Motor Complication Stage

In later stages, motor fluctuations and dyskinesias frequently develop. These are influenced by long-term dopaminergic therapy interacting with progressive neuronal loss.

Wearing-off refers to shortening of medication benefit before the next dose. On-off phenomena describe unpredictable shifts between mobility and immobility. Dyskinesias are involuntary movements that often occur at peak medication effect [9].

These motor complications do not necessarily indicate sudden acceleration of disease but reflect evolving dopamine receptor sensitivity and synaptic adaptation.

Axial and Gait Dominant Stage

As Parkinson’s disease advances further, axial symptoms become prominent. These include freezing of gait, postural instability, camptocormia, and reduced stride length.

Freezing episodes can occur suddenly, especially when turning or walking through narrow spaces. Falls become more frequent and represent a major source of hospitalization and injury.

Stage 4 and stage 5 in the Hoehn and Yahr scale correspond to severe disability, where assistance with mobility or confinement to wheelchair or bed may occur [5].

Cognitive and Behavioral Progression

Motor staging alone does not capture the full course of Parkinson’s disease. Cognitive decline may evolve gradually, beginning with executive dysfunction and slowed processing speed. Some patients progress to Parkinson’s disease dementia in later stages.

Behavioral complications such as hallucinations or impulse control disorders may also emerge over time, influenced by both disease progression and medication exposure [9].

Tracking cognitive trajectory is therefore as important as monitoring motor decline.

Autonomic and Multisystem Progression

Autonomic dysfunction may worsen as disease advances. Orthostatic hypotension, urinary dysfunction, constipation, and temperature regulation disturbances may intensify.

Swallowing difficulty may progress from mild inefficiency to aspiration risk. In advanced stages, nutritional decline and weight loss can occur. These changes reflect broader neurodegenerative involvement beyond the basal ganglia [6].

Variability in Rate of Progression

Progression speed varies significantly between individuals. Factors influencing trajectory include:

• Age at onset

• Baseline cognitive reserve

• Comorbid medical conditions

• Initial symptom pattern

• Treatment responsiveness

Some individuals experience slow progression over decades, while others show faster functional decline. Early gait instability or early cognitive impairment may predict a more complex course [9].

Clinical Tracking and Monitoring

Effective management requires structured longitudinal assessment. The Hoehn and Yahr scale provides global staging, while more detailed instruments such as the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale quantify motor and non-motor symptom severity [5] [9].

Tracking should include:

• Motor symptom burden

• Medication response duration

• Fall frequency

• Cognitive status

• Autonomic symptoms

• Swallowing function

Regular assessment distinguishes between disease progression, medication side effects, and emergence of atypical features.

Why Understanding Progression Matters

Parkinson’s disease progression affects not only mobility but also cognition, autonomy, safety, and caregiver demand. A comprehensive view of staging integrates motor, cognitive, autonomic, and psychosocial domains.

Recognizing progression patterns early allows timely rehabilitation, medication optimization, fall prevention strategies, and long-term care planning [5] [6].

Progression is inevitable in most cases, but its impact can be moderated through structured monitoring and multidisciplinary management [9].

Diagnosis in Clinic- What Neurologists Actually Do

Parkinson’s disease is diagnosed clinically. There is no single blood test or routine imaging scan that confirms it. Instead, neurologists rely on a structured clinical evaluation, longitudinal observation, and response to treatment to establish the diagnosis [1].

Because Parkinson’s is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder with overlapping features shared by other conditions, careful differentiation is essential. Modern diagnostic frameworks emphasize systematic assessment rather than reliance on tremor alone [1] [26].

Step 1: Detailed Clinical History

The diagnostic process begins with a comprehensive history. Neurologists ask about:

• Onset and pattern of tremor

• Slowness of movement

• Stiffness or reduced arm swing

• Balance changes or falls

• Constipation, sleep disturbance, mood changes

• Medication exposure

• Family history

Particular attention is paid to asymmetry. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease often begins on one side and remains asymmetric for years [1].

A history of early severe falls, rapid progression, or minimal response to medication may suggest atypical parkinsonism rather than classic Parkinson’s disease [26].

Step 2: Neurological Examination

The neurological exam focuses on identifying cardinal motor features.

Bradykinesia

Bradykinesia is required for diagnosis. The neurologist assesses repetitive finger tapping, hand opening and closing, and foot tapping to detect slowness and progressive reduction in movement amplitude [1].

Rigidity

Passive movement of the limbs assesses resistance. Cogwheel rigidity may be detected during examination.

Resting Tremor

A classic resting tremor often appears when the limb is relaxed and diminishes with action.

Postural Instability

Balance testing evaluates fall risk. Early severe postural instability may raise concern for atypical syndromes [26].

Diagnosis requires bradykinesia plus either rigidity or resting tremor under established clinical criteria [1].

Step 3: Applying Diagnostic Criteria

Neurologists often use internationally recognized criteria to guide diagnosis. These criteria include:

• Presence of parkinsonism

• Absence of exclusion criteria

• Presence of supportive features

Supportive criteria may include clear benefit from dopaminergic therapy, presence of resting tremor, and progression over time [1].

Red flags such as rapid decline, early cognitive impairment, severe autonomic failure, or symmetrical onset prompt further evaluation for atypical parkinsonian disorders [26].

Step 4: Medication Response Assessment

A practical diagnostic tool is observing response to levodopa. Most individuals with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease demonstrate significant improvement in motor symptoms when treated with dopaminergic therapy [23].

A poor or absent response may suggest an alternative diagnosis, although interpretation must be cautious and individualized.

Step 5: Role of Imaging

Routine MRI is not used to confirm Parkinson’s disease but may be ordered to exclude structural causes such as stroke, tumor, or normal pressure hydrocephalus.

In uncertain cases, dopamine transporter imaging may be used to evaluate presynaptic dopaminergic integrity. However, imaging supports but does not replace clinical judgment [26].

Step 6: Differentiating From Similar Conditions

Neurologists must differentiate Parkinson’s disease from:

• Essential tremor

• Drug-induced parkinsonism

• Multiple system atrophy

• Progressive supranuclear palsy

• Corticobasal degeneration

Early severe autonomic failure, gaze palsy, symmetrical onset, or rapid progression often point toward atypical parkinsonism rather than idiopathic disease [26].

Step 7: Longitudinal Confirmation

Parkinson’s diagnosis is often confirmed over time. Follow-up visits allow the neurologist to observe progression pattern, medication responsiveness, and emergence of new features.

Because early symptoms can overlap with other movement disorders, longitudinal observation remains a critical diagnostic tool [1].

What Diagnosis Is Not

Parkinson’s disease diagnosis is not based solely on tremor. It is not confirmed by routine blood testing. It is not ruled out by a normal MRI.

It is a clinical diagnosis supported by structured examination, established criteria, and careful follow-up [1] [23].

Why Accurate Diagnosis Matters

Correct diagnosis guides treatment decisions, informs prognosis, and determines eligibility for advanced therapies. Misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate medication exposure, delayed management of atypical syndromes, and avoidable complications [26].

A methodical clinical approach remains the gold standard in Parkinson’s disease evaluation [1].

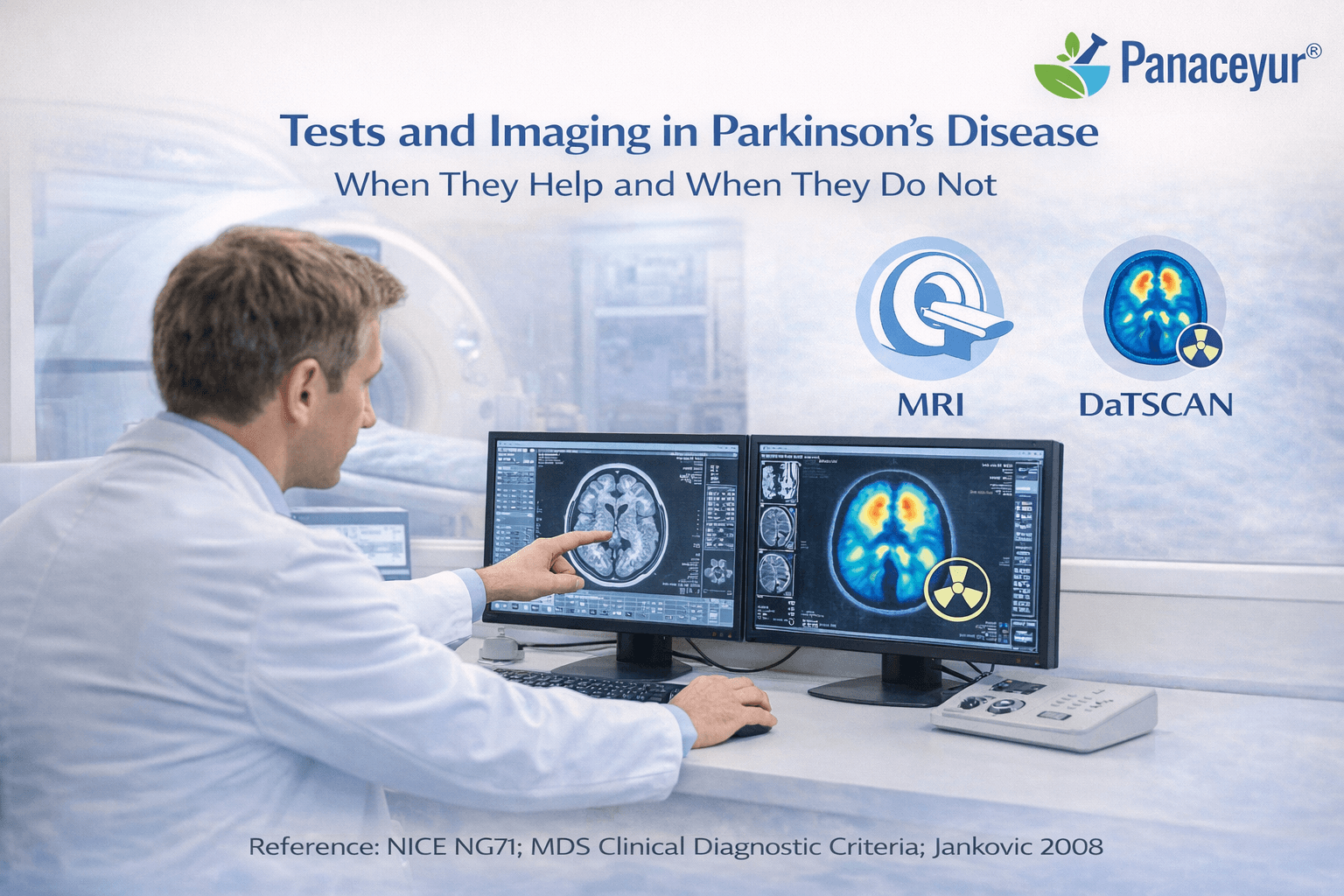

Tests and Imaging in Parkinson’s Disease-When They Help and When They Do Not

Parkinson’s disease remains primarily a clinical diagnosis. No routine laboratory test confirms it, and no single imaging modality definitively establishes the condition in early stages. Neurologists rely first on history and examination, using tests and imaging selectively to support diagnosis or exclude alternative causes [1].

Understanding when investigations add value, and when they do not, prevents over-testing and misinterpretation.

When Routine Blood Tests Help

There is no blood test that confirms Parkinson’s disease. However, basic laboratory investigations are often ordered to rule out reversible or mimicking conditions.

Thyroid dysfunction, vitamin B12 deficiency, metabolic imbalance, and certain inflammatory or infectious conditions can produce tremor, cognitive impairment, or gait disturbance. Blood tests therefore assist in excluding secondary causes rather than diagnosing Parkinson’s itself [1].

In typical cases with clear clinical features, laboratory testing serves a supportive, not confirmatory, role.

MRI Brain: Exclusion Rather Than Confirmation

Magnetic resonance imaging is commonly performed during the initial work-up. However, a normal MRI does not exclude Parkinson’s disease.

MRI is primarily used to rule out structural causes of parkinsonism such as stroke, tumor, normal pressure hydrocephalus, or extensive small vessel disease. In idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, conventional MRI often appears normal, especially in early stages [1] [15].

Imaging becomes particularly important when clinical features are atypical, such as rapid progression, early cognitive decline, or symmetrical onset.

Dopamine Transporter Imaging

Dopamine transporter imaging evaluates presynaptic dopaminergic neuron integrity. In Parkinson’s disease, reduced dopamine transporter binding may be observed.

This test can help differentiate Parkinson’s disease from essential tremor when clinical findings are ambiguous. However, it does not distinguish between idiopathic Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonian syndromes, as both may show dopaminergic deficit [1].

Dopamine transporter imaging supports but does not replace clinical judgment. It is most useful in diagnostically uncertain cases.

Levodopa Response as a Functional Test

Response to levodopa remains one of the most practical diagnostic tools. Most individuals with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease demonstrate meaningful motor improvement with dopaminergic therapy [23].

A poor or absent response may raise suspicion for atypical parkinsonism, although dosage adequacy and timing must be carefully evaluated before drawing conclusions.

Levodopa response should be interpreted as part of the broader clinical picture rather than a standalone diagnostic criterion.

When Imaging Does Not Add Value

In a patient with classic asymmetric onset, bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, and typical progression, additional imaging rarely changes management. Overuse of advanced imaging in clear clinical presentations may increase cost without improving diagnostic accuracy [1].

Routine repeated imaging during follow-up is also not standard practice unless new neurological deficits or atypical features emerge.

Emerging Biomarkers and Research Tools

Research continues into imaging biomarkers, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and molecular markers of alpha-synuclein pathology. However, these remain investigational and are not yet standard clinical diagnostic tools [15].

At present, Parkinson’s disease diagnosis remains rooted in careful clinical assessment rather than laboratory confirmation.

Practical Clinical Perspective

Neurologists use tests and imaging selectively to:

• Exclude structural brain lesions

• Differentiate essential tremor

• Clarify atypical or rapidly progressive cases

• Support uncertain diagnoses

They do not rely on tests to confirm typical Parkinson’s disease.

The most reliable diagnostic tools remain structured history, neurological examination, progression pattern, and medication responsiveness [1] [23].

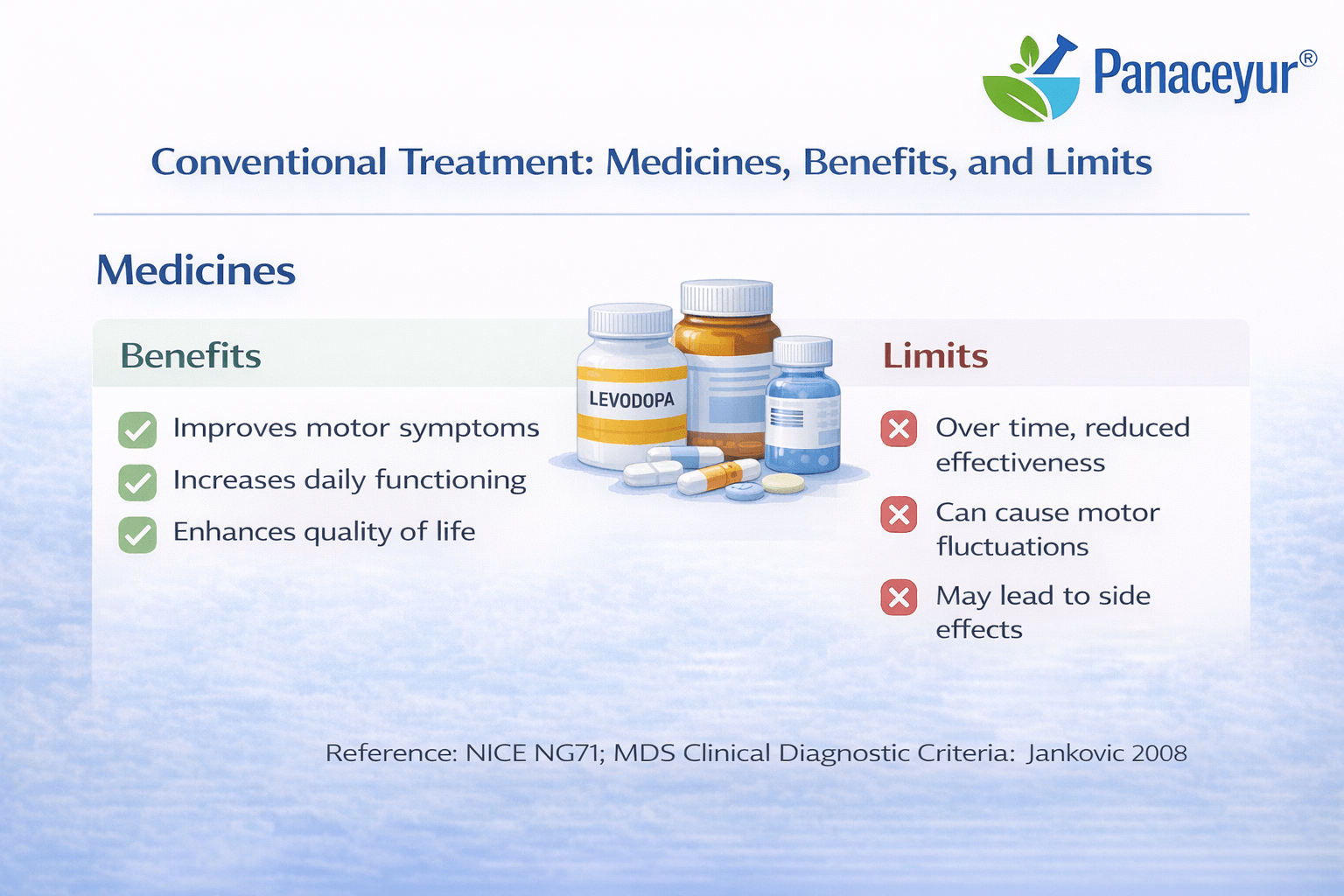

Conventional Treatment- Medicines, Benefits, and Limits

Conventional treatment for Parkinson’s disease is designed to reduce symptoms, preserve independence, and improve quality of life. Modern medical therapy is highly effective in controlling motor features, especially in early and moderate stages. However, it does not reverse the underlying neurodegenerative process or restore lost neurons. Current global guidelines emphasize individualized treatment plans that balance symptom relief with long-term safety and complication risk [10] [26].

Levodopa and Dopamine Replacement

Levodopa remains the most effective medication for managing motor symptoms. It is converted into dopamine in the brain and directly compensates for dopamine deficiency in the basal ganglia. Patients often experience significant improvement in slowness, stiffness, and tremor after initiation. Functional mobility, handwriting, facial expression, and walking speed frequently improve during early therapy.

Over time, however, the response pattern may change. As neuronal loss progresses, the duration of benefit from each dose may shorten, leading to wearing-off. Some individuals develop involuntary movements known as dyskinesias at peak medication effect. These motor complications reflect altered dopamine receptor responsiveness and synaptic adaptation rather than abrupt disease acceleration [10] [24].

Dopamine Agonists and Adjunct Medications

Dopamine agonists stimulate dopamine receptors directly and may be used in early disease or in combination with levodopa. They can extend motor benefit and reduce immediate reliance on higher levodopa doses. However, they carry higher risk of impulse control disorders, hallucinations, excessive sleepiness, and peripheral edema. Careful patient selection and ongoing monitoring are required [11].

Monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors and catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors are commonly used as adjunct therapies. These agents prolong dopamine availability in the brain and are particularly useful in managing wearing-off phenomena. Their benefit is supportive rather than transformative, and they do not modify long-term neurodegeneration [10].

Management of Non-Motor Symptoms

Conventional care extends beyond dopamine replacement. Depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, constipation, orthostatic hypotension, and cognitive impairment require separate evaluation and targeted treatment. These symptoms often respond to multidisciplinary approaches that include pharmacological therapy, physiotherapy, speech therapy, and psychological support. Structured guidelines emphasize comprehensive symptom review during follow-up visits because non-motor symptoms significantly affect long-term quality of life [11] [26].

Advanced Therapies in Later Stages

In patients with disabling motor fluctuations despite optimized medication, advanced therapies may be considered. Device-assisted treatments such as continuous dopaminergic infusion or deep brain stimulation are used selectively in appropriate candidates. These interventions can reduce motor fluctuations and improve functional stability. However, they do not halt disease progression and require careful neurological evaluation before implementation [26].

Benefits of Conventional Treatment

Conventional treatment provides substantial and often life-changing improvement in mobility and daily function. Many patients maintain independence for years with structured medication regimens. Evidence-based guidelines provide a standardized framework for safe prescribing and monitoring [10]. For motor symptom control, conventional therapy remains highly effective.

Limits of Conventional Treatment

Despite its strengths, conventional treatment does not restore degenerating neurons or eliminate alpha-synuclein pathology. Motor complications may develop with long-term therapy, and non-motor symptoms may persist or progress independently of motor improvement. Cognitive decline and autonomic dysfunction can evolve even when tremor and rigidity are well managed. Comparative long-term studies confirm that current medication strategies optimize symptom control but do not constitute a disease-modifying cure [24].

Understanding both the benefits and limitations of conventional therapy allows realistic expectation setting and informed decision-making. Conventional medicine excels in symptom management and structured care delivery, yet its focus remains largely on dopamine replacement rather than comprehensive neurodegenerative reversal [10] [11].

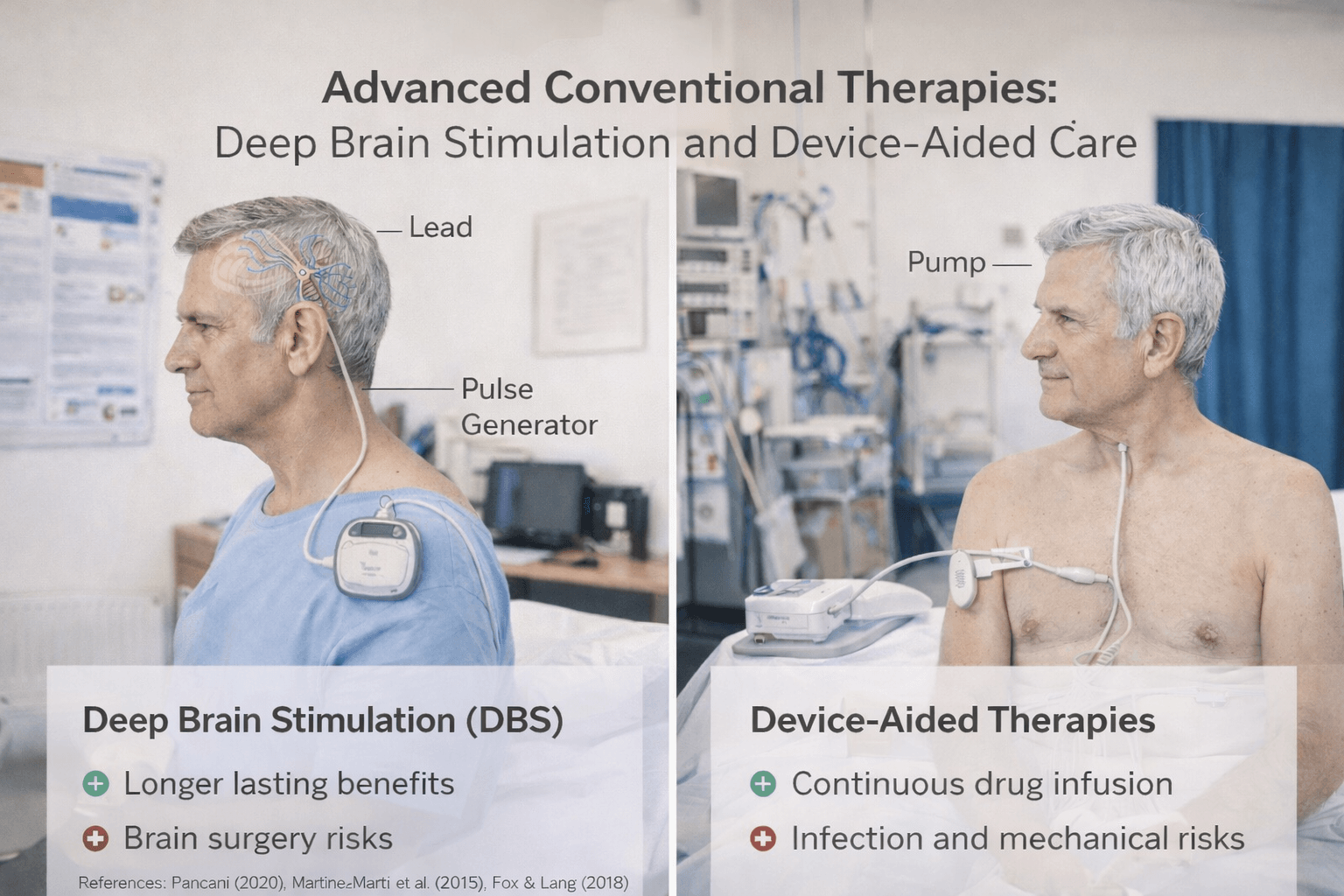

Advanced Conventional Therapies: Deep Brain Stimulation and Device-Aided Care

As Parkinson’s disease progresses, some patients develop disabling motor fluctuations or dyskinesias that cannot be adequately controlled with optimized oral medication alone. In such cases, advanced conventional therapies may be considered. These interventions are not first-line treatments but are reserved for carefully selected individuals whose quality of life is significantly affected despite best medical management [10].

Deep Brain Stimulation

Deep brain stimulation, commonly known as DBS, is a surgical procedure in which electrodes are implanted into specific regions of the brain, most often the subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus interna. These electrodes deliver controlled electrical impulses that modulate abnormal neural activity within motor circuits.

Large randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that DBS can significantly improve motor function and reduce medication requirements in selected patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease [3] [4]. Many individuals experience marked reduction in tremor, decreased motor fluctuations, and improved daily functioning after surgery.

However, DBS is not a cure. It does not stop disease progression or prevent the development of non-motor complications. Cognitive decline, mood disorders, and autonomic dysfunction may continue independently of motor improvement. Careful patient selection is critical. Ideal candidates typically have a strong response to levodopa but experience severe motor fluctuations or dyskinesias. Patients with advanced dementia or uncontrolled psychiatric illness are generally not considered suitable candidates [10] [27].

Continuous Dopaminergic Infusion Therapies

For patients who are not ideal surgical candidates, device-aided pharmacological therapies may be considered. These approaches provide continuous dopaminergic stimulation to reduce motor fluctuations caused by intermittent oral dosing.

One strategy involves continuous subcutaneous infusion of dopaminergic medication, while another uses intestinal gel formulations delivered through a percutaneous tube system. By maintaining steadier dopamine levels, these therapies reduce wearing-off and unpredictable on-off periods.

Device-aided therapies can significantly stabilize motor symptoms in advanced disease, but they require technical support, monitoring, and patient commitment. They also do not alter the underlying neurodegenerative process [10].

Benefits of Advanced Therapies

Advanced therapies offer meaningful improvement for appropriately selected patients. Benefits may include:

• Reduction in motor fluctuations

• Decreased dyskinesia severity

• Lower medication burden

• Improved mobility and independence

Clinical trial data confirm that in well-selected individuals, DBS provides superior motor control compared to best medical therapy alone in advanced stages [3] [4].

Limitations and Risks

Despite their benefits, advanced therapies carry limitations. Surgical risks for DBS include infection, bleeding, hardware complications, and neuropsychiatric effects. Device-aided infusion therapies may involve tube-related complications or local skin reactions.

Importantly, these interventions primarily target motor symptoms. Non-motor symptoms such as cognitive decline, depression, and autonomic dysfunction often persist or progress. Long-term disease evolution continues despite motor improvement [27].

Clinical Perspective

Advanced conventional therapies represent a major achievement in modern neurology. They provide significant symptom control for selected patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease. However, they do not eliminate neurodegeneration or prevent long-term multisystem progression.

Careful multidisciplinary evaluation, including neurological, cognitive, and psychological assessment, is essential before proceeding with surgical or device-based treatment [10].

Understanding both the power and limits of advanced therapies helps patients make informed decisions regarding timing, expectations, and long-term planning.

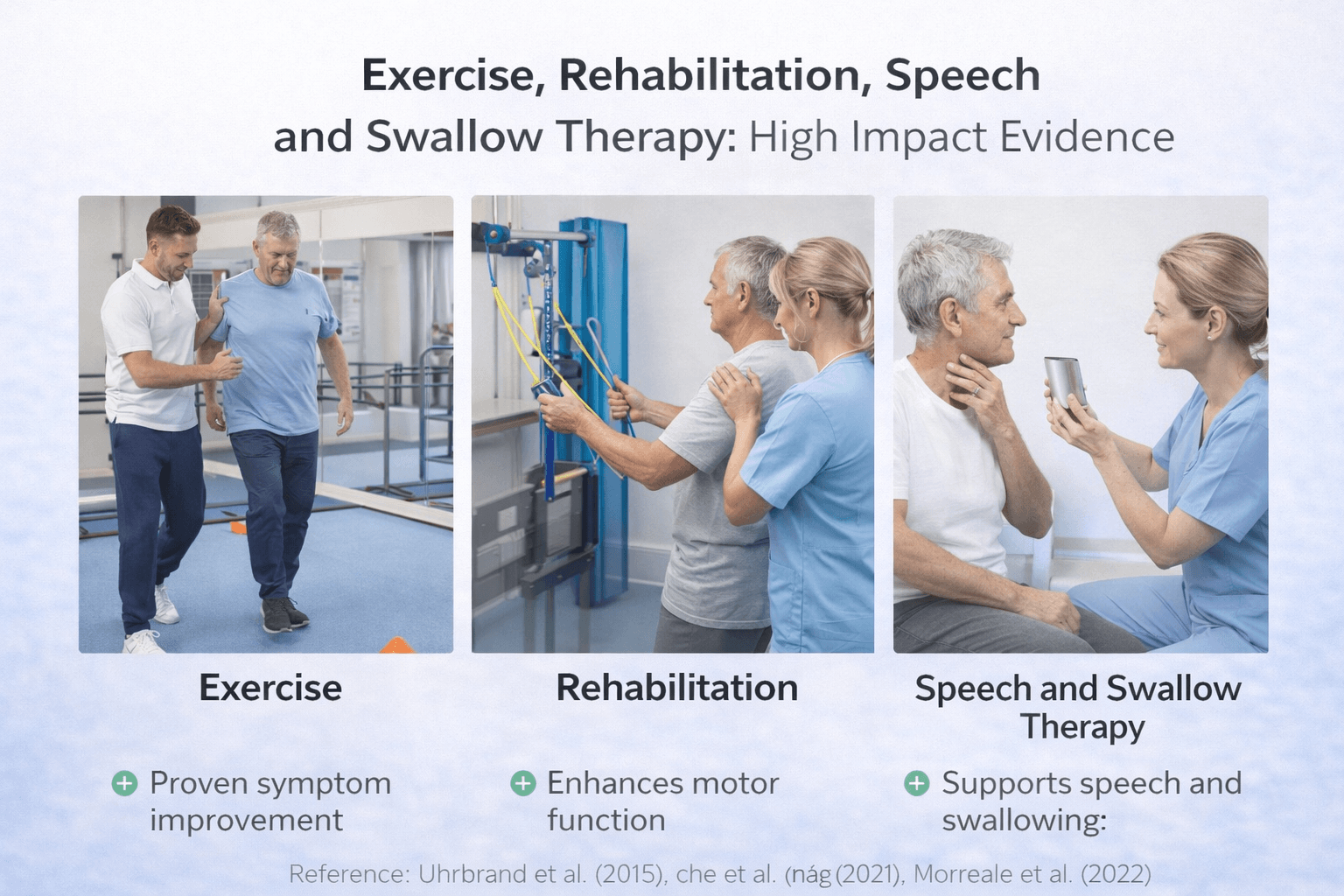

Exercise, Rehabilitation, Speech and Swallow Therapy- High Impact Evidence

In modern Parkinson’s care, structured rehabilitation is not considered optional or secondary. Exercise and multidisciplinary therapy are core components of management and have measurable impact on mobility, balance, and quality of life. Unlike pharmacological treatment, which primarily targets dopamine deficiency, rehabilitation supports neuroplasticity, functional compensation, and long-term independence [13] [14].

High-quality clinical trials and systematic reviews demonstrate that consistent physical training improves motor performance and may slow functional decline when implemented early and maintained over time [32].

Structured Exercise as Therapeutic Intervention

Randomized trials show that high-intensity aerobic exercise, including treadmill-based training, can significantly improve motor symptoms in early Parkinson’s disease [13]. Exercise appears to enhance motor control, increase gait speed, and improve balance confidence.

Importantly, exercise is not limited to general fitness. Programs are often tailored to Parkinson’s-specific challenges, including:

• Gait retraining

• Balance training

• Postural correction

• Strength and resistance training

• Dual-task cognitive-motor drills

Systematic reviews confirm that regular exercise improves mobility and functional outcomes across disease stages [14].

Mechanistically, exercise may support dopaminergic signaling efficiency, enhance cortical plasticity, and reduce secondary deconditioning. While it does not reverse neurodegeneration, it meaningfully improves daily performance and reduces fall risk.

Physiotherapy and Gait Training

Targeted physiotherapy focuses on restoring amplitude and coordination of movement. Techniques may include cue-based walking strategies, rhythmic auditory stimulation, and turning practice to reduce freezing of gait.

Evidence supports that supervised physiotherapy improves stride length, walking speed, and balance stability [32]. Early implementation produces better outcomes than delayed referral.

Speech Therapy and Voice Training

Hypophonia, characterized by reduced voice volume, is common in Parkinson’s disease. Speech therapy programs, including structured vocal training protocols, help improve voice projection and articulation.

Speech therapy may also address communication fatigue and swallowing coordination. Early referral is encouraged because speech changes can gradually worsen without intervention.

Swallow Therapy and Dysphagia Management

Swallowing dysfunction increases risk of aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, and dehydration in advanced stages. Speech-language pathologists perform structured swallow evaluations and recommend targeted exercises or dietary modifications.

Early intervention reduces aspiration risk and improves nutritional safety. Swallow therapy is especially important in patients reporting coughing during meals or recurrent chest infections.

Occupational Therapy and Functional Adaptation

Occupational therapists assist patients in maintaining independence in daily activities. Adaptive strategies, environmental modification, and energy conservation techniques improve safety and reduce caregiver burden.

This multidisciplinary model aligns with international guidelines recommending early and sustained rehabilitation involvement [14].

Evidence-Based Impact

High-quality randomized trials and meta-analyses consistently show that exercise and rehabilitation produce meaningful improvements in mobility, balance, and daily function [13] [14].

Clinical reviews further reinforce that exercise should be prescribed with the same seriousness as medication, particularly in early disease stages [32].

Unlike device-based therapies reserved for advanced cases, exercise and rehabilitation are appropriate across all stages and carry minimal risk when supervised properly.

Clinical Perspective

Exercise and multidisciplinary rehabilitation represent high-impact, evidence-supported interventions in Parkinson’s disease. They do not eliminate the underlying neurodegenerative process, but they significantly influence functional trajectory, fall prevention, and quality of life.

Early initiation, structured supervision, and long-term adherence are critical for sustained benefit [13] [32].

Risk Factors and Prevention-Focused Lifestyle Framing

Parkinson’s disease is considered multifactorial, meaning it arises from a combination of genetic susceptibility, environmental exposure, aging-related neurodegeneration, and biological vulnerability. While no intervention has been definitively proven to prevent Parkinson’s disease, understanding recognized risk patterns allows realistic, evidence-aligned public health guidance suitable for UK and USA audiences [18] [31].

Age as the Primary Risk Factor

Advancing age remains the strongest and most consistent risk factor. The majority of diagnoses occur after age 60, with prevalence increasing significantly in older populations. As life expectancy rises globally, overall disease burden is expected to increase correspondingly [31].

Age-related neuronal vulnerability, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein misfolding are believed to contribute to this increased risk.

Sex and Epidemiological Patterns

Men are diagnosed more frequently than women. Although the exact reason remains unclear, hypotheses include hormonal influences, environmental exposure patterns, and genetic susceptibility differences [18].

However, women with Parkinson’s disease may experience different symptom profiles, particularly in non-motor domains.

Genetic Susceptibility

While most cases are sporadic, a minority involve identifiable genetic mutations. Family history modestly increases risk, but the majority of patients do not have a strong hereditary pattern.

Genetics alone rarely determines outcome; gene-environment interaction likely plays a substantial role.

Environmental and Occupational Exposure

Certain environmental exposures have been associated with increased risk. These include pesticide exposure and rural occupational settings. The relationship is associative rather than universally causal, and risk magnitude varies between populations.

Public health recommendations emphasize minimizing prolonged exposure to known neurotoxic agents where possible [18].

Head Trauma

Repetitive or severe head injury has been associated with increased Parkinson’s risk in some epidemiological studies. Protective measures, including helmet use and fall prevention strategies, are encouraged for general neurological safety.

Lifestyle and Modifiable Factors

Although no lifestyle intervention guarantees prevention, evidence-informed health behaviors may support overall neurological resilience.

Regular physical activity is associated with improved motor function and may contribute to broader neuroprotective mechanisms through improved vascular health and mitochondrial efficiency.

Balanced nutrition, cardiovascular health optimization, sleep hygiene, and management of metabolic risk factors support general brain health.

Importantly, prevention messaging must remain realistic. There is currently no validated strategy that eliminates Parkinson’s disease risk. Public guidance focuses on reducing modifiable exposures and promoting general neurological wellness rather than promising prevention [18].

Population Trends and Public Health Framing

Prevalence in the United Kingdom continues to rise, reflecting demographic aging rather than epidemic contagion [31]. Similar patterns are seen in the United States and globally.

From a health systems perspective, prevention strategies emphasize early recognition, fall prevention, cardiovascular optimization, and supportive care planning rather than primary disease eradication.

Medication and Treatment Exposure

Long-term treatment studies comparing medication strategies do not indicate that current pharmacological therapy increases disease incidence. Instead, treatment approaches focus on optimizing symptom management after diagnosis rather than altering pre-diagnostic risk [23].

Clinical Perspective

Risk factors for Parkinson’s disease involve age, genetic predisposition, environmental exposure, and possibly prior neurological injury. While no intervention guarantees prevention, healthy lifestyle practices that support vascular and metabolic health align with broader neurological protection principles.

Public guidance in the UK and USA emphasizes realistic expectations, avoidance of unproven claims, and evidence-based health behaviors rather than definitive preventive promises [18] [31].

Prodromal Parkinson’s and Early Detection

Prodromal Parkinson’s refers to the phase in which neurodegenerative changes are likely underway, but the classic motor signs required for a clinical Parkinson’s diagnosis have not yet fully appeared. This concept matters because many people experience non motor symptoms years before diagnosis, and early identification may allow closer monitoring, earlier supportive intervention, and better planning. However, it is equally important to separate what is clinically validated from what remains research based, because prodromal markers are probabilistic, not definitive [2].

What Is Clinically Validated Today

In current clinical practice, neurologists do not diagnose Parkinson’s disease based only on prodromal symptoms. Nevertheless, certain features are widely accepted as meaningful clinical clues when they occur persistently, especially in combination or alongside subtle motor changes. Among these, REM sleep behaviour disorder stands out as one of the most important. It involves dream enactment behaviours during REM sleep, such as shouting, punching, or falling from bed, due to loss of normal muscle atonia. When REM sleep behaviour disorder is confirmed clinically, it warrants neurological awareness and long term follow up because it is strongly associated with synuclein related neurodegeneration [7] [30].

What is considered validated in a practical sense is that REM sleep behaviour disorder can be an early indicator of future Parkinson’s related disorders, but it is not a diagnostic confirmation by itself. Clinical validation here means it is reliable enough to trigger monitoring and risk counselling, not that it proves a person will develop Parkinson’s disease [7] [30].

What Is Strong Evidence but Still Not a Diagnosis

Longitudinal studies and systematic reviews show that individuals with idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder have a substantial long term risk of developing a synucleinopathy such as Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies over time. This is one of the strongest prodromal signals currently known, particularly when symptoms are severe, persistent, and documented in a sleep medicine context [7].

Even with this strong association, the correct clinical framing is risk based, not certainty based. Some individuals convert earlier, some later, and a minority may not convert within observed study timelines. Therefore, clinicians treat this as a high risk marker that justifies monitoring, sleep safety counselling, and periodic neurological review rather than immediate labeling as Parkinson’s disease [7] [30].

What Is Research Only

The Movement Disorder Society research criteria for prodromal Parkinson’s are designed for research and risk stratification, not for routine diagnosis. These criteria combine multiple risk factors and markers into a probability estimate of prodromal Parkinson’s disease. The key point is that this framework is intended to identify high likelihood individuals for research studies and surveillance, not to provide a definitive clinical diagnosis in general practice [2].

Under this model, different markers contribute different weight to the probability calculation, and the outcome is a likelihood estimate rather than a yes or no diagnosis. This research structure helps scientists study early disease biology and evaluate potential early interventions, but it must be communicated carefully to patients because it can be misunderstood as confirmation of Parkinson’s disease [2].

Practical Early Detection Approach for Patients and Clinicians

A clinically responsible early detection strategy focuses on pattern recognition and appropriate referral rather than self diagnosis. If a person has persistent REM sleep behaviour disorder symptoms, or a combination of sleep disturbance and subtle evolving neurological changes, the appropriate next step is formal evaluation by a clinician, often involving sleep assessment and neurological examination. The goal is to clarify risk, ensure safety, and establish a monitoring plan that avoids unnecessary alarm while still respecting the evidence that certain prodromal states are meaningful [7] [30].

In summary, prodromal Parkinson’s is a scientifically grounded concept, and REM sleep behaviour disorder is one of the strongest early markers supported by longitudinal evidence. However, validated does not mean diagnostic. The research criteria provide probability based stratification for studies, while clinical practice focuses on careful evaluation, safety, and follow up rather than premature labeling [2] [7].

Prognosis, Life Expectancy Framing, Quality of Life, and Caregiver Reality

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic, progressive neurological disorder, but prognosis varies significantly between individuals. Life expectancy is influenced by age at onset, overall health status, cognitive trajectory, fall risk, and complications such as aspiration or infection. Modern treatment has significantly improved functional years after diagnosis, yet the disease remains progressive over time [23] [19].

Life Expectancy: What the Data Actually Shows

Population-based projections indicate that the global burden of Parkinson’s disease is rising, primarily due to aging populations rather than sudden increases in disease aggressiveness [19]. In many patients, especially those diagnosed later in life, life expectancy may not be dramatically shortened in early and moderate stages when motor symptoms are well managed.

However, mortality risk increases in advanced disease, particularly when complications such as recurrent falls, aspiration pneumonia, severe cognitive decline, or autonomic instability emerge. Studies analyzing severity-based outcomes show that later-stage Parkinson’s disease is associated with increased healthcare utilization and higher mortality risk compared to earlier stages [29].

Prognosis should therefore be framed dynamically. Early stages often allow years of meaningful function, while advanced stages require structured monitoring and support.

Disease Modification Versus Symptom Control

Long-term clinical trials comparing early versus delayed levodopa therapy show that while dopaminergic treatment significantly improves motor symptoms, it does not demonstrate definitive disease-modifying cure [21].

This distinction is central to realistic prognosis discussions. Medication enhances mobility and daily functioning but does not eliminate neurodegeneration. Therefore, prognosis reflects a balance between symptomatic improvement and gradual biological progression.

Functional Trajectory and Quality of Life

Quality of life in Parkinson’s disease depends not only on tremor severity but also on cognitive health, mood stability, fall prevention, and social engagement.

Motor fluctuations, dyskinesias, fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbance all influence perceived well-being. Even when life expectancy remains relatively stable, quality of life can decline if non-motor symptoms are not adequately addressed.

Severity-based multinational studies demonstrate that economic burden, caregiver stress, and hospitalization risk increase substantially as disease severity advances [29]. These findings highlight that prognosis must include functional and social dimensions, not only survival statistics.

Cognitive Progression and Long-Term Outlook

Cognitive impairment significantly alters long-term trajectory. Patients who develop dementia experience greater dependency, increased fall risk, and higher institutional care rates.

While not all individuals progress to dementia, cognitive decline is a critical determinant of long-term independence. Monitoring executive function and memory helps anticipate care needs and plan interventions proactively.

Complications That Influence Prognosis

The most serious complications affecting survival and functional decline include:

• Recurrent falls leading to fractures

• Aspiration pneumonia due to dysphagia

• Severe autonomic instability

• Advanced cognitive impairment

Early detection and structured intervention reduce risk but do not eliminate long-term vulnerability.

Caregiver Reality and Social Impact

Parkinson’s disease affects families as much as patients. As disease severity increases, caregiver involvement expands from supervision to hands-on assistance with mobility, hygiene, medication management, and feeding.

Caregiver strain correlates strongly with motor fluctuations, behavioral changes, and cognitive decline. Multinational burden studies confirm that advanced Parkinson’s disease substantially increases caregiver time commitment and economic impact [29].

Psychological stress, fatigue, and social isolation are common among caregivers, particularly in later stages.

Framing Prognosis Responsibly

Prognosis discussions should avoid both extremes. Parkinson’s disease is not immediately life threatening in early stages, nor is it a uniformly benign condition. It is a progressive disorder whose trajectory varies widely.

Modern therapy enables many individuals to maintain independence for years after diagnosis [23]. However, as disease severity increases, risk of complications rises, and comprehensive care planning becomes essential.

Population projections underscore that Parkinson’s disease will remain a growing public health concern due to demographic trends [19]. This reinforces the importance of early diagnosis, structured follow-up, rehabilitation, and caregiver support planning.

In summary, prognosis in Parkinson’s disease is best understood as a long-term functional trajectory influenced by age, cognitive health, complication prevention, and multidisciplinary care. Life expectancy may remain substantial in early stages, but quality of life and caregiver impact must be actively managed throughout the disease course [21] [29].

Economic Burden in the UK and USA- Cost, Access, and Disability

Parkinson’s disease is not only a neurological disorder but also a substantial economic and social challenge. As prevalence rises with aging populations, the financial burden on individuals, families, and healthcare systems continues to grow. Projections indicate that global case numbers are increasing steadily, amplifying long-term cost implications [19].

Direct Medical Costs

Direct medical expenses include outpatient visits, neurological consultations, medication costs, hospital admissions, rehabilitation services, and advanced therapies such as device-assisted treatments.

In the United States, economic modeling studies estimate that Parkinson’s disease generates billions of dollars annually in combined direct and indirect costs. Updated projections demonstrate that total annual burden includes healthcare spending, prescription medications, surgical interventions, and long-term care services, with costs expected to rise significantly over the coming decades [34].

Earlier estimates also confirm that Parkinson’s imposes a substantial financial strain at both individual and national levels, particularly as disease severity advances [33].

In the United Kingdom, while the structure of the National Health Service differs from the US system, financial burden remains significant. Costs are distributed across hospital care, community services, medication coverage, and social care support. Although universal healthcare reduces out-of-pocket expenses for many patients, indirect costs and social care needs remain substantial [35].

Indirect Costs and Productivity Loss

Indirect costs often exceed direct medical expenses. These include:

• Loss of employment or reduced work capacity

• Early retirement

• Reduced household income

• Caregiver work disruption

• Disability-related financial strain

In the United States, workforce exit and reduced productivity contribute significantly to total economic burden. Younger onset patients may experience decades of income loss. Severity-based modeling confirms that costs escalate as functional independence declines [34].

In the United Kingdom, indirect costs include reliance on disability benefits, social support systems, and unpaid caregiving by family members. Economic analyses demonstrate that family caregiving constitutes a major hidden cost not always captured in healthcare expenditure data [35].

Cost Escalation With Disease Severity

The financial burden of Parkinson’s disease increases progressively with severity. Multinational data show that advanced stages are associated with higher hospitalization rates, greater medication complexity, increased need for assistive devices, and more intensive caregiver involvement [29].

As mobility declines and cognitive impairment emerges, long-term care placement or extensive home support becomes more common, further raising economic impact.

Access to Advanced Therapies

In the United States, access to advanced therapies such as deep brain stimulation may depend on insurance coverage, geographic location, and specialist availability. Disparities in access can influence outcomes.

In the United Kingdom, advanced therapies are available through structured referral pathways within the NHS, but regional variation in access and waiting times may affect timing of intervention.

Economic capacity, healthcare infrastructure, and regional service availability therefore shape patient experience in both countries.

Disability and Social Impact

Parkinson’s disease is a leading cause of neurological disability in aging populations. Progressive motor impairment increases fall risk, limits mobility, and reduces capacity for independent living. Cognitive decline and psychiatric complications further compound disability burden.

As projected prevalence continues to rise globally, the societal cost associated with disability, caregiver support, and healthcare resource allocation is expected to expand correspondingly [19].

Long-Term Economic Outlook

Economic projections indicate that without transformative disease-modifying interventions, the financial burden of Parkinson’s disease will continue to increase over coming decades. Aging populations in both the UK and USA amplify this trend [19] [34].

The economic reality reinforces the importance of early diagnosis, structured rehabilitation, fall prevention strategies, caregiver support systems, and coordinated multidisciplinary care.

Clinical and Public Health Perspective

Parkinson’s disease imposes significant direct medical costs, indirect productivity losses, and long-term disability-related expenses in both the UK and USA. As disease severity increases, costs escalate sharply due to hospitalizations, advanced therapies, and caregiver dependency [33] [34] [35].

Addressing economic burden requires not only medical management but also policy-level planning, caregiver support structures, and sustainable healthcare system adaptation in response to rising prevalence [19].

Ayurveda Perspective: Kampavata Mapping Within Classical Framework