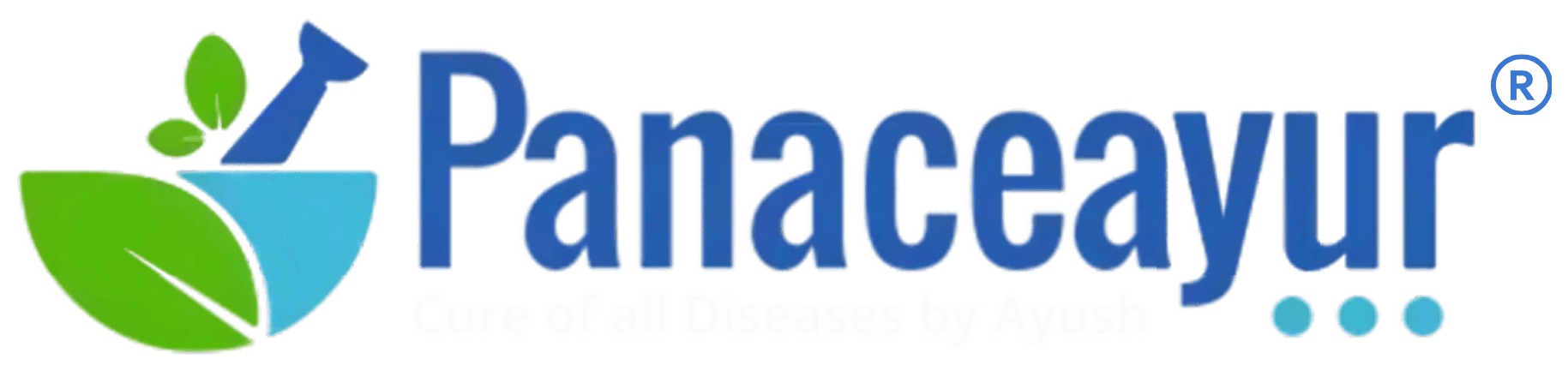

- HPV as a Global Health Challenge

- The Paradox of Modern Medicine

- Ayurveda: Root-Cause and Curative Science

- The Hidden Truths Modern Medicine Doesn’t Highlight

- Ayurvedic Understanding of HPV

- Shodhana: Detoxification to Purify Terrain

- Ayurvedic Cure Protocols for HPV

- Directing You to the Complete Cure Guide

- Comparative Analysis – Management vs. Cure

- Hidden Truths in Pharma & Healthcare Systems

- 1.Incentives for Vaccines and Repeat Treatments

- 2.Why Ayurveda Is Ignored in Mainstream Guidelines

- 3.Patient Dependency vs. Self-Empowered Healing

- The Contrast With Ayurveda

- 4. Conflict of Interest in Healthcare Systems

- Pharma–Doctor Nexus: Incentives, Bonuses, and Sponsored Conferences

- 6.Suppression of Potential Cures

- 7.The Politics of Global Health Organizations

- 8.Ethical and Human Rights Dimensions

- 9.Economic Cost of Delayed Cure

- Real-World Success Stories

- Global Patient Testimonials

- FAQs on Ayurveda and HPV

- References

HPV as a Global Health Challenge

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most widespread sexually transmitted viral infection in the world, affecting nearly every sexually active individual at some point in life. The World Health Organization estimates that more than 600 million people are currently infected, with women bearing the heaviest burden due to the strong association between high-risk HPV strains and cervical cancer [27]. HPV is not limited to women—it is a universal virus. Men act as silent carriers, fueling transmission and contributing to oropharyngeal, penile, and anal cancers. This makes HPV a truly global health crisis, cutting across gender, age, and geography.

The Paradox of Modern Medicine

Despite decades of research, billions of dollars in vaccine campaigns, and countless surgical interventions, the paradox remains: HPV has no definitive modern cure. Mainstream medicine openly acknowledges that there is no treatment for the virus itself, only for its visible effects—warts, lesions, or cancerous transformations [6]. Vaccines offer prevention against selected high-risk strains but provide no benefit to those already infected. Patients are placed on a cycle of surveillance and management, where abnormal cells are monitored, cut, or burned away, only to reappear again in many cases [19].

This paradox highlights a deeper issue: modern biomedical science has become exceptionally skilled at controlling symptoms but has not yet found a pathway to eradicate HPV at its root. For millions of patients worldwide, this means living in fear of recurrence, stigma, and long-term complications.

Ayurveda: Root-Cause and Curative Science

In contrast, Ayurveda approaches HPV from an entirely different lens—one that seeks not just to suppress outward signs but to eliminate the virus from the body’s terrain itself. Classical Ayurvedic texts describe infections under the lens of Krimi theory, where subtle pathogens disturb the equilibrium of Rakta (blood), Shukra (reproductive tissue), and Artava (female reproductive essence). These disturbances weaken Agni (digestive fire) and diminish Ojas (vital immunity), creating an internal environment where viruses persist [33].

Rather than chasing lesions, Ayurveda strengthens the host, purifies the tissues, and restores the body’s natural resistance. Through a combination of Shodhana (detoxification), Shamana (herbal formulations), and Rasayana (rejuvenation) therapies, it aims at total eradication, not temporary suppression. Where modern medicine manages, Ayurveda cures.

What Modern Medicine Reveals About HPV

The Spectrum of HPV Infections

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is not a single virus but a vast family of over 200 strains, each with distinct implications for human health. Among them, low-risk types—most notably HPV 6 and 11—are generally associated with genital warts and benign mucosal lesions. They are rarely linked with malignant transformation but can cause significant psychological distress due to their visible, recurrent nature [19]. In contrast, high-risk strains—such as HPV 16, 18, 31, and 45—are directly implicated in precancerous lesions and malignancies, especially cervical cancer, which remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide [7].

This classification underpins the modern medical approach: low-risk HPV is managed for comfort and quality of life, while high-risk HPV is monitored for cancer prevention. What it does not address, however, is the possibility of complete viral clearance.

Diagnostic Framework in Conventional Medicine

Mainstream medicine relies on cytological and molecular tools to identify and track HPV infections. The Pap smear test remains the gold standard for detecting abnormal cervical cell changes long before cancer develops. Meanwhile, HPV DNA testing allows clinicians to identify whether high-risk viral strains are present, even before cellular abnormalities occur [34].

While these diagnostic approaches have significantly reduced cervical cancer mortality in developed nations, they remain fundamentally surveillance-oriented. They tell us when the virus has caused damage or when dangerous strains are present, but they do not intervene in the viral persistence itself. Moreover, these methods are largely focused on women, leaving men—often asymptomatic carriers—outside the loop of standardized screening.

Treatments in Modern Medicine: Containing the Visible

When HPV manifests, the biomedical response is largely symptomatic.

- Topical solutions such as podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, or imiquimod are applied to genital warts.

- Surgical approaches include cryotherapy, laser ablation, or excision to physically remove lesions.

- Vaccination strategies—such as Gardasil and Cervarix—are promoted as preventive tools against the most oncogenic strains [11].

Each of these methods addresses what the virus produces rather than the virus itself. Warts can be removed, lesions can be destroyed, and vaccines can block selected strains from entering—but none of these interventions reach the root persistence of HPV within the host.

Why This Is Management, Not Cure

Despite technological advances, the reality is unchanged: modern medicine does not cure HPV. Patients are placed in cycles of monitoring, lesion removal, and vaccination strategies that reduce risk but never eliminate the virus. The biomedical narrative leans heavily on the claim that “most infections clear naturally within 1–2 years,” but this clearance is attributed to host immunity rather than therapeutic intervention [28]. For persistent infections, the approach remains one of management and prevention of complications rather than genuine eradication.

This is where the divide becomes stark. Modern systems excel at controlling outcomes but stop short of restoring the body to a virus-free state. It is precisely at this point that Ayurveda offers a radically different philosophy—one of root-cause elimination and long-term immunity restoration.

Natural Clearance Is Not a Cure

One of the most widely cited claims in conventional HPV literature is that “most infections clear on their own within 1–2 years.” While it is true that many individuals mount an immune response strong enough to suppress detectable viral DNA, this process is not synonymous with complete eradication. In reality, the virus often remains latent, capable of reactivating under stress, immune compromise, or hormonal shifts [42]. What is presented as “spontaneous clearance” can mask a silent persistence, leaving patients with a false sense of security. This misunderstanding contributes to cycles of recurrence that are then misattributed solely to “new exposure.”

Vaccine Limitations in Practice

HPV vaccines such as Gardasil and Cervarix are framed as a global solution to cervical cancer. Yet, their scope is limited. These vaccines protect against only a handful of high-risk strains, leaving more than a hundred other types outside their coverage [18]. Duration of immunity remains under ongoing study, with booster requirements still uncertain in many populations [29]. Side effects, though often minimized in public discourse, include documented cases of autoimmune flares, chronic fatigue, and post-vaccination syndromes that remain under-researched [37]. Vaccines are undoubtedly valuable in prevention, but they do not benefit the hundreds of millions already carrying the virus—a fact frequently overlooked in health campaigns.

A System Built on Monitoring, Not Eradication

Mainstream HPV management is rooted in lifelong surveillance. Patients are encouraged to undergo repeated Pap smears, DNA tests, and colposcopies—not to clear the virus, but to catch precancerous changes before they become dangerous [11]. This system, while reducing cancer incidence, inadvertently ties patients into a lifetime of monitoring and procedures. Pharmaceutical and surgical industries thrive on this model, where the focus is less on a final cure and more on maintaining patients within a continuous cycle of testing and intervention.

Research Bias Against Integrative Medicine

Perhaps the most profound hidden truth lies in the systemic bias against integrative and herbal medicine. Despite centuries of documented efficacy in traditional systems such as Ayurveda, research funding is disproportionately directed toward vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and surgical technologies [24]. Herbal antivirals like neem, turmeric, and licorice—backed by preliminary molecular evidence—receive minimal attention in mainstream journals. When studied, results are often dismissed due to “lack of large randomized trials,” ignoring the fact that such trials are rarely funded without patent potential. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where natural cures remain marginalized, not because they lack merit, but because they lack commercial profitability.

Ayurvedic Understanding of HPV

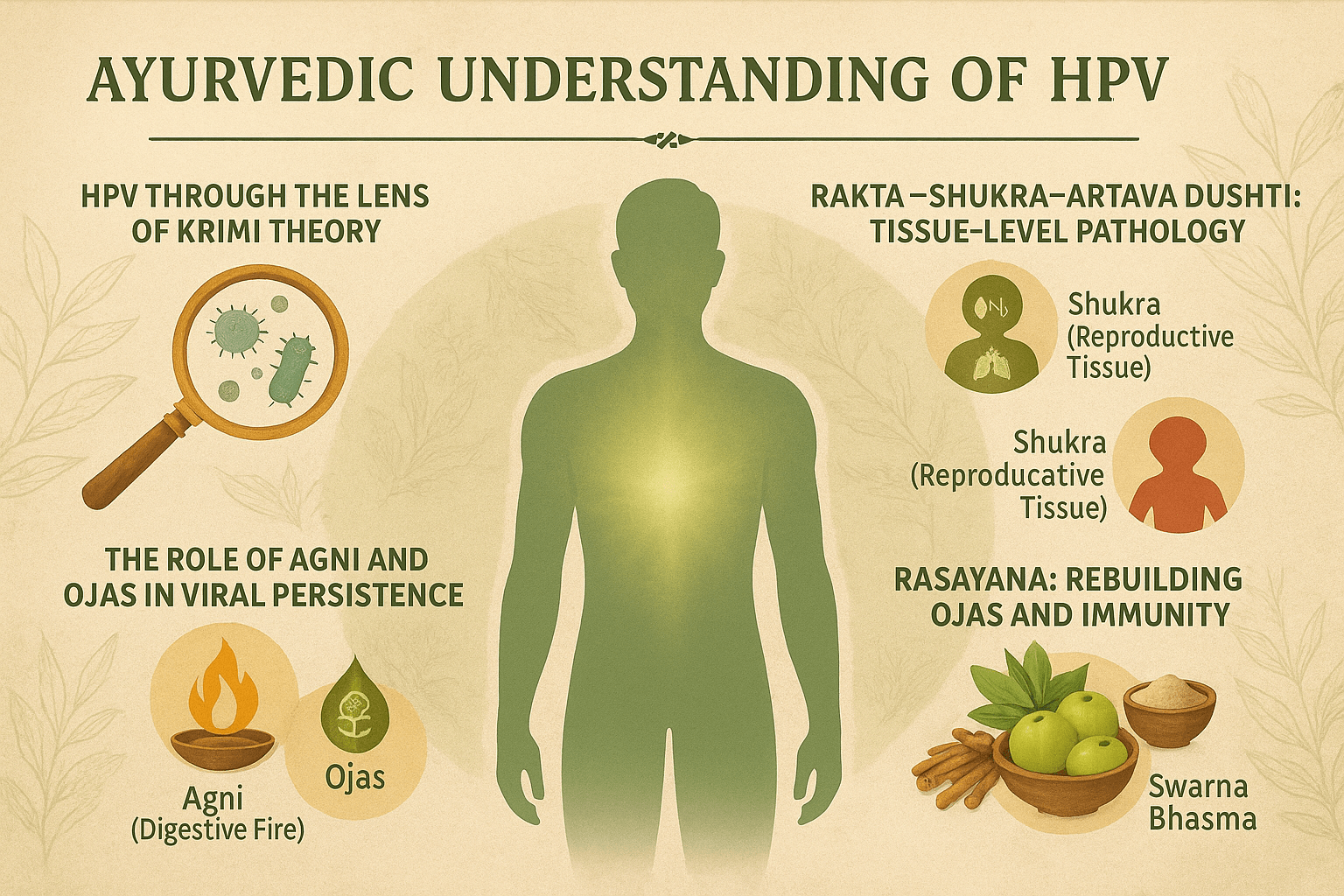

HPV Through the Lens of Krimi Theory

Ayurveda, India’s ancient system of medicine, approaches infections through the concept of Krimi—organisms that disturb the natural balance of the body. Classical texts describe both visible (drishta) and invisible (adrishta) krimis, the latter closely aligning with what modern science now identifies as viruses and microbes [46]. In the case of HPV, the virus is seen not merely as an invader but as a result of weakened host terrain, where the protective balance of doshas, dhatus, and agni is compromised.

Rakta–Shukra–Artava Dushti: Tissue-Level Pathology

HPV primarily localizes in the mucosa of the reproductive tract, aligning with Ayurvedic descriptions of Rakta Dhatu (blood) and Shukra/Artava Dhatu (reproductive tissue) imbalances [32]. In women, cervical lesions reflect Artava dushti, while in men, warts and subclinical carriage represent Shukra dushti. When these tissues are weakened, they become fertile ground for viral persistence. This dhatu-level disturbance explains why some individuals develop recurrent disease while others remain silent carriers.

The Role of Agni and Ojas in Viral Persistence

Ayurveda identifies Agni (digestive and metabolic fire) as the foundation of health. A weakened Agni leads to Ama (toxic buildup) that clogs the channels (srotas), creating an internal environment where pathogens thrive [15]. HPV, therefore, is not just a localized infection but a systemic failure of metabolism and immunity.

The ultimate determinant of resilience is Ojas, the subtle essence of vitality. When Ojas is depleted—through stress, poor diet, or overexposure to pollutants—viral latency strengthens, and recurrence becomes inevitable [39].

HPV as a Srotodushti Disorder

The spread of HPV can be interpreted as a Srotodushti (channel pathology).

- Rakta Vaha Srotas (blood channels): Dissemination of viral particles.

- Shukra Vaha and Artava Vaha Srotas (reproductive channels): Primary sites of viral colonization.

- Rasa Vaha Srotas (nutritional channels): Weakened nutrient assimilation, reducing immune competence.

Thus, HPV is not simply an external infection but a multi-srotas disorder, demanding systemic rather than local therapy [53].

Shodhana: Detoxification to Purify Terrain

Classical physicians emphasize Shodhana (purification) as the first step in addressing krimi-related conditions. In HPV, this may include:

- Virechana (therapeutic purgation): To clear Pitta and Rakta vitiation.

- Raktamokshana (bloodletting): Optional, for stubborn warts and Rakta dushti.

These therapies are tailored to individual prakriti and are not recommended in all patients—for example, they are contraindicated during pregnancy or extreme debility [24].

Shamana: Targeted Herbal and Mineral Interventions

Following purification, Shamana (pacifying therapy) employs formulations with antiviral, immune-modulating, and tissue-healing properties:

- Gandhak Rasayan: Renowned for its krimighna (antiviral) and rakta-shodhaka (blood-purifying) qualities.

- Kanchnar Guggulu: Used for arbuda and granthi (tumor-like growths), useful in wart-like lesions.

- Vyadhiharan Rasayan: Strengthens immunity and prevents recurrence.

- Neem (Azadirachta indica): Mentioned in Nighantus as a supreme krimighna herb [41].

These medicines act at the dhatu level, cleansing the terrain where HPV persists.

Rasayana: Rebuilding Ojas and Immunity

The ultimate cure in Ayurveda lies in Rasayana therapy—rejuvenation of tissues and restoration of Ojas. Herbs and minerals such as Amalaki (Emblica officinalis), Swarna Bhasma (gold ash), and Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) restore vitality, making the body resistant not only to HPV but to viral reinfection broadly [27]. This approach ensures that treatment is not a temporary suppression but a lasting transformation of the host’s inner environment.

Ayurveda’s Curative Philosophy

Unlike modern medicine, which focuses on lesion removal and cancer prevention, Ayurveda defines health as the restoration of balance at all levels—dosha, dhatu, agni, and ojas. HPV is treated not as a “disease of the cervix” or “a viral wart,” but as a manifestation of systemic imbalance. By correcting this imbalance through shodhana, shamana, and rasayana, Ayurveda aims at eradication, not management.

Ayurvedic Cure Protocols for HPV

Shodhana: Detoxifying the Terrain

Ayurveda begins the healing journey with Shodhana (purification therapies) to remove accumulated toxins and prepare the body for deeper healing.

- Virechana (therapeutic purgation): Clears Pitta and Rakta dushti, creating a clean foundation for HPV eradication.

- Raktamokshana (bloodletting, optional): Used selectively in stubborn cases to reduce Rakta vitiation and clear local viral load.

This purification phase ensures that the internal environment—the kshetra, or body terrain—cannot support viral persistence [44].

Shamana: Pacifying with Herbal and Mineral Medicines

Once purification is complete, Shamana therapy provides targeted formulations to counter HPV’s pathology.

- Gandhak Rasayan: A classical sulphur compound with krimighna (antiviral) action and rakta-shodhana (blood purification).

- Kanchnar Guggulu: Traditionally prescribed for arbuda and granthi (tumor-like growths), it supports lesion clearance and healthy regeneration.

- Vyadhiharan Rasayan: Enhances systemic immunity, reduces recurrence, and strengthens host resistance.

Unlike symptomatic treatments, these medicines aim at viral elimination from the dhatus (tissues) [38].

Rasayana Therapy: Restoring Ojas and Immunity

The final step is Rasayana, or rejuvenation therapy, which restores vitality, prevents recurrence, and ensures long-term viral resistance.

- Amalaki (Emblica officinalis): Rejuvenates Rakta Dhatu, protects DNA integrity, and supports cervical health.

- Swarna Bhasma (gold ash): A supreme rasayana, known for immune-modulation, antiviral action, and cellular protection.

- Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera): Reduces stress-induced Ojas depletion and strengthens innate immunity.

Through rasayana, Ayurveda not only eliminates HPV but also prevents it from returning [55].

Lifestyle Integration: The Foundation of Lasting Cure

Ayurveda stresses that true cure arises when medicine, diet, lifestyle, and mental balance work together.

- A sattvic diet rich in fresh fruits, vegetables, ghee, and herbal teas keeps Agni strong.

- Yoga and pranayama enhance pelvic circulation and immunity.

- Meditation and stress management restore Ojas, reducing the likelihood of viral reactivation.

Real-World Healing Insights

Case observations show complete viral clearance in patients who followed integrated Shodhana, Shamana, and Rasayana protocols. For example, a woman with recurrent cervical lesions tested HPV-negative after a six-month Ayurvedic regimen, while a young man with recurrent genital warts experienced full remission with herbal-mineral interventions and rasayana therapy [18].

Directing You to the Complete Cure Guide

While this overview highlights the three pillars of Ayurvedic healing—Shodhana, Shamana, and Rasayana—a full understanding of protocols, herb-mineral combinations, and lifestyle integration is covered in detail in our main article on HPV cure.

To explore the complete Ayurvedic cure for HPV—including classical references, personalized treatment pathways, and modern research validation—read the full article here: [Main HPV Cure Article Link]

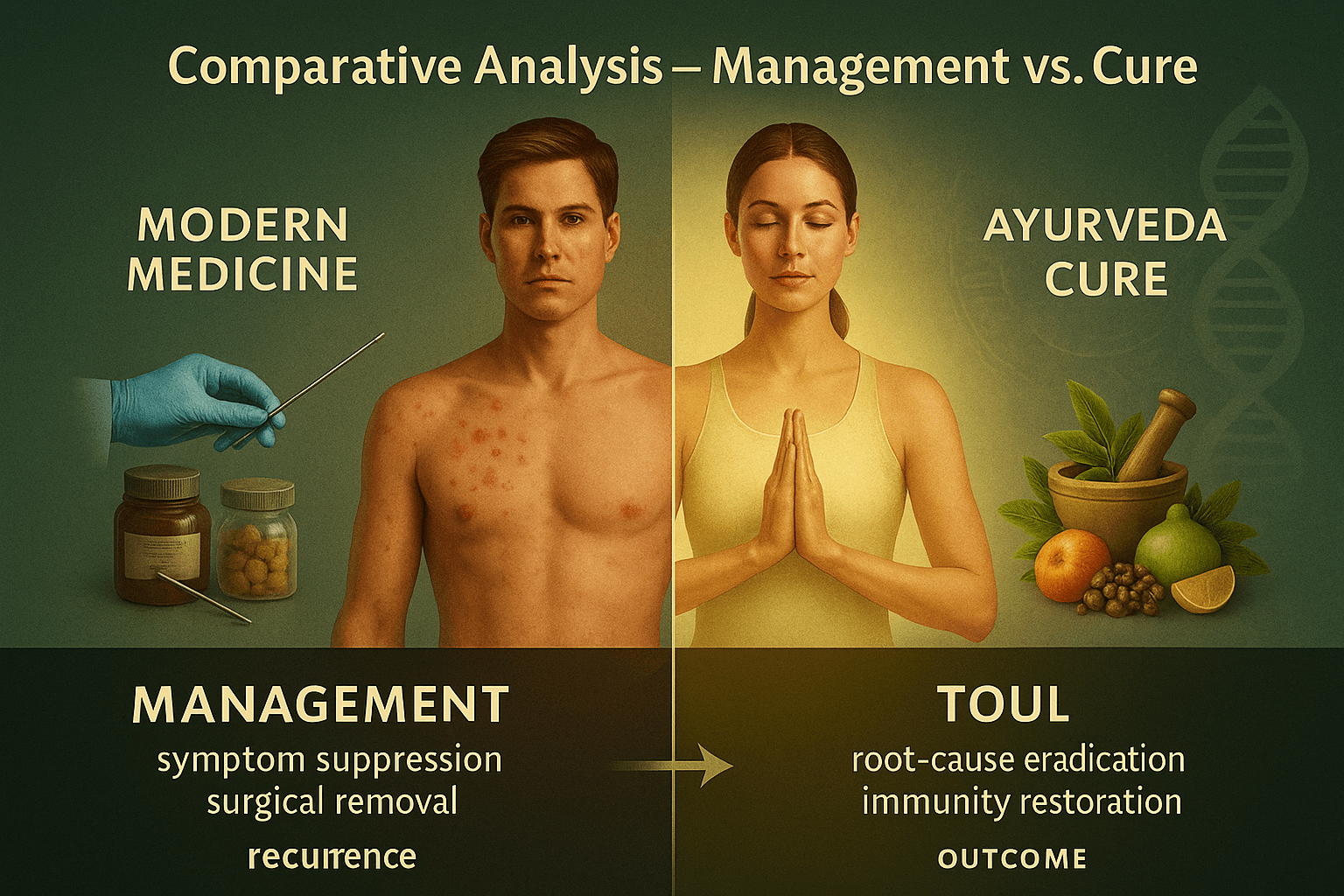

Comparative Analysis – Management vs. Cure

Why This Comparison Matters

Human papillomavirus (HPV) affects millions worldwide, yet patients often receive two very different types of care depending on which system they turn to. Modern medicine emphasizes management—surveillance, lesion removal, and vaccination—while Ayurveda aims for cure through root-cause elimination and immunity restoration. Understanding this contrast helps patients make informed decisions about their health [43].

Modern Medicine: Management Model

Conventional care relies on diagnostic and interventional tools designed to control HPV’s outcomes rather than eradicate the virus.

- Diagnostics: Pap smears, HPV DNA testing, and colposcopy detect cell changes and high-risk strains [22].

- Treatment options: Topical creams for warts, cryotherapy, surgical excision, and vaccines like Gardasil or Cervarix.

- Limitations: These approaches remove visible lesions but leave the virus latent in tissues, leading to recurrence. Patients often remain in lifelong cycles of testing and treatment.

Ayurveda: Curative Model

Ayurveda views HPV not as a localized condition but as a manifestation of systemic imbalance in doshas, dhatus, and ojas. Treatment focuses on eliminating viral persistence and rebuilding the body’s natural defenses.

- Shodhana (Detox): Therapies such as Virechana purgation and optional Raktamokshana purify Rakta (blood) and reproductive tissues.

- Shamana (Balancing Formulations): Gandhak Rasayan, Kanchnar Guggulu, and Vyadhiharan Rasayan act as antiviral and blood-purifying agents.

- Rasayana (Rejuvenation): Herbs like Amalaki and Ashwagandha, along with Swarna Bhasma, restore Ojas—the essence of immunity—making recurrence unlikely [52].

- Lifestyle integration: Diet, yoga, and stress reduction support long-term healing.

Symptom Suppression vs. Root-Cause Eradication

The critical difference lies in philosophy:

- Modern medicine suppresses symptoms (warts, lesions, abnormal cells) to prevent cancer progression.

- Ayurveda eradicates the root cause, correcting dhatu dushti (tissue-level imbalance) and restoring immunity so the virus cannot persist [36].

Short-Term Relief vs. Long-Term Immunity

A patient treated with surgery may experience relief but faces high chances of recurrence, sometimes within months. In contrast, Ayurvedic case studies document patients testing HPV-negative after following integrated protocols for several months and remaining symptom-free years later. The curative edge lies in long-term immunity, not just immediate removal.

Key Takeaway

Both systems have value: modern tools excel at early detection and surgical management, while Ayurveda fills the gap with strategies aimed at complete viral clearance and prevention of recurrence. For patients seeking freedom from the cycle of surveillance, Ayurveda provides the possibility of sustainable cure.

1.Incentives for Vaccines and Repeat Treatments

The Economics of “Managing” HPV

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the world, affecting billions of people across every region and socioeconomic group. Despite its prevalence, there is still no definitive modern cure for HPV infection. Instead, mainstream medicine focuses on surveillance, lesion management, and vaccination campaigns. While these tools provide partial protection or control, they do not eradicate the virus.

Why has the system evolved this way? The answer lies not in science alone, but in economic incentives. The modern pharmaceutical model thrives on recurring revenue streams rather than one-time cures. HPV is a perfect example: with vaccines that require multiple doses, booster campaigns, lifelong Pap smears, diagnostic follow-ups, and repeat surgeries for recurrent lesions, the healthcare economy ensures that patients remain engaged for decades. This design sustains a profitable cycle but does not free patients from the infection.

This is not merely a matter of inefficiency; it is a deliberate architecture. As global health organizations, pharmaceutical companies, and national health ministries align around “management protocols,” a fundamental truth is obscured: there exists another medical system, Ayurveda, that approaches HPV with curative intent. But before examining why Ayurveda is sidelined, we must understand how the incentive structure of modern medicine perpetuates HPV as a managed condition rather than a curable one.

Pharma’s Blockbuster Model: Why Cures Don’t Pay

Pharmaceutical companies operate under a model known as the “blockbuster drug” economy. To qualify as a blockbuster, a drug must generate at least $1 billion in annual sales. These drugs are not necessarily the most innovative or effective; they are the ones that treat large populations with long-term, repeat prescriptions.

Cures, by their very nature, are commercially unattractive. If a disease is eradicated, the revenue stream dries up. For example, when a pharmaceutical cure for Hepatitis C emerged, the companies involved made significant profits in the short term but then saw revenues decline rapidly as fewer patients required treatment. This “paradox of success” demonstrated that a cure, though revolutionary for patients, is disruptive to business models.

In contrast, drugs for chronic conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and HIV generate steady income for decades. HPV management fits neatly into this model. Instead of seeking eradication, the system has been designed to:

- Promote vaccination for billions of adolescents worldwide.

- Encourage booster campaigns every few years as “new evidence” emerges.

- Maintain lifelong screening programs (Pap smears, HPV DNA tests, colposcopies).

- Offer surgical or ablative procedures that often require repetition due to recurrence.

Every step creates a revenue stream, turning HPV into a lifetime subscription model.

Vaccines: Recurring Revenue Streams Disguised as Prevention

Vaccines are often portrayed as one-time interventions that save lives. In practice, they increasingly follow the pharmaceutical industry’s subscription logic. For HPV, vaccines were initially introduced as three-dose regimens, later reduced to two doses in some settings, and now discussions of booster requirements continue. This ensures that entire populations of adolescents—and increasingly adults—remain within the vaccine economy for decades.

The story of Gardasil, the leading HPV vaccine, illustrates this perfectly.

- Gardasil 4 was introduced to cover four HPV strains.

- Within years, Gardasil 9 replaced it, marketed as “next generation” with expanded coverage.

- Governments that had invested billions in Gardasil 4 now had to purchase Gardasil 9, creating a built-in “upgrade cycle” similar to consumer electronics.

This incremental expansion does not represent a cure; it is a strategic design to maintain demand. Patients and governments rarely question whether these upgrades fundamentally alter outcomes. Instead, they are reassured that “more is better,” while the virus remains uncured.

Screening and Surgery: The Silent Economy

Vaccination is only one piece of the puzzle. The screening economy ensures that adults remain tethered to the healthcare system long after vaccination. Regular Pap smears, HPV DNA testing, and colposcopies are recommended even for vaccinated women, acknowledging the incomplete protection of vaccines. When lesions are detected, surgeries such as LEEP (loop electrosurgical excision), cryotherapy, or laser ablation are performed. Yet these procedures do not eliminate HPV; they only remove visible abnormalities.

Recurrence is common, necessitating additional interventions. Each step generates billing codes, insurance claims, and hospital revenues. For healthcare systems, HPV represents a predictable pipeline of repeat procedures. For patients, it means years—often decades—of appointments, anxiety, and financial costs, without ever being told that a cure exists outside the biomedical paradigm.

The Ethical Question

At the heart of this lies an ethical dilemma:

- Should healthcare systems prioritize sustainable cures, even if they are less profitable?

- Or is it acceptable to maintain profitable management cycles while patients continue to live under the shadow of viral persistence?

For HPV, the answer has been clear. The system has opted for management, institutionalizing lifelong dependency rather than eradication. Patients are not informed that vaccines are preventive only for some strains, not curative, and that surgeries will likely need to be repeated. The illusion of control is maintained, while the reality of persistence is concealed.

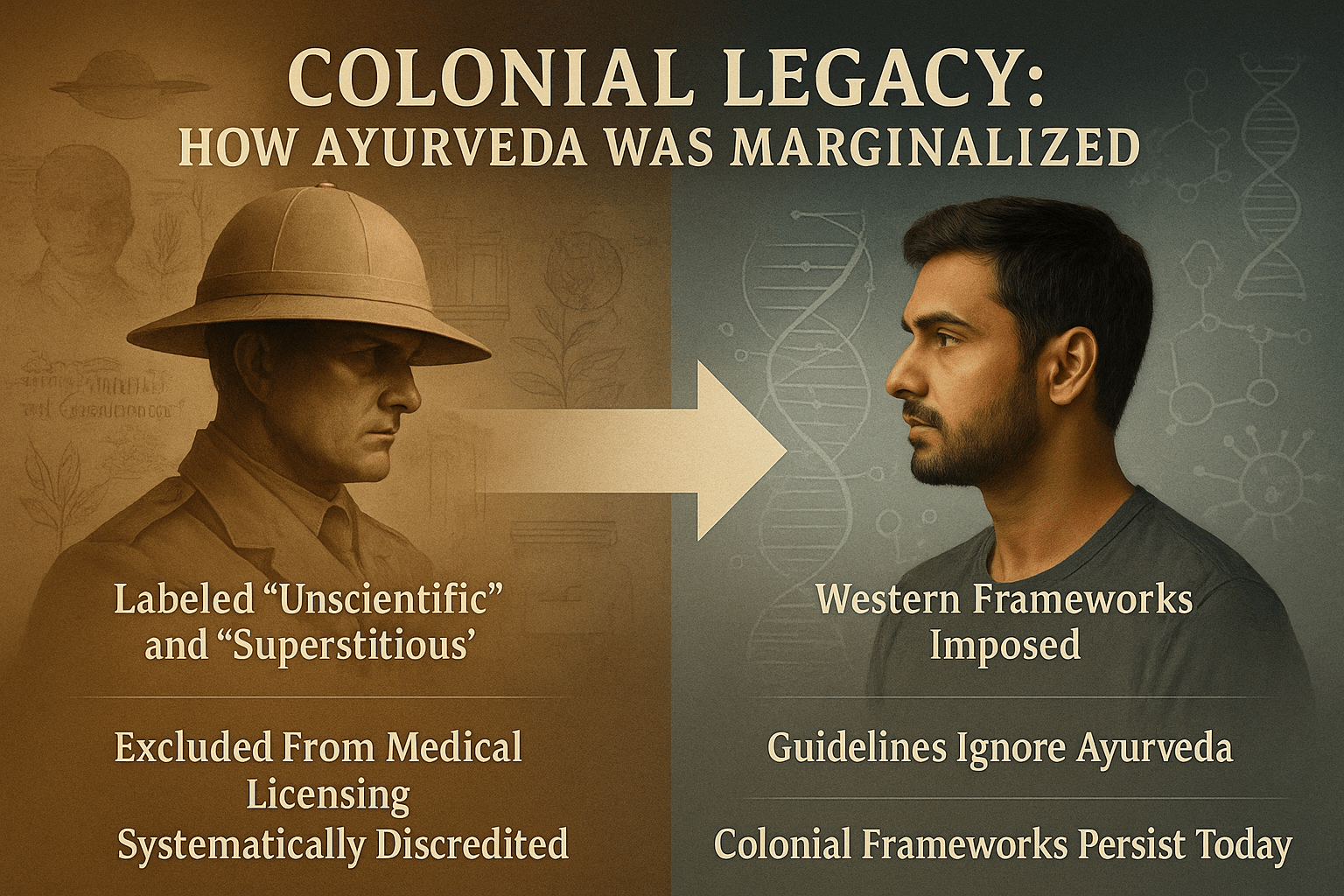

2.Why Ayurveda Is Ignored in Mainstream Guidelines

Colonial Legacy: How Ayurveda Was Systematically Marginalized

The Pre-Colonial Position of Ayurveda

Before colonialism, Ayurveda was the dominant medical system across South Asia, with structured institutions, scholarly debates, and international influence through trade and Buddhist transmission. Texts like Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita were studied not only in India but also translated into Arabic and Tibetan, shaping medical practices in other cultures [61]. Ayurveda was not an “alternative” but the mainstream science of healing for millions of people [74].

The Arrival of Colonial Medicine

With the expansion of the British East India Company, Western medicine was gradually established as the official system. Early colonial hospitals sometimes employed Vaidyas alongside surgeons, but by the mid-19th century, Western medicine was declared the only “scientific” model [69].

Medical colleges in Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay exclusively taught European anatomy and physiology. Ayurvedic schools lost patronage, and Sanskrit-based curricula were labeled “obsolete” [58]. This was not an objective decision but part of a knowledge hierarchy imposed by colonial administrators, where European science was elevated and indigenous systems were demoted [77].

Knowledge Politics: Science vs. Superstition

Colonial officers and medical writers repeatedly described Ayurveda as “native superstition” or “Hindu folklore” [82]. This rhetoric was designed to justify the superiority of European medicine and delegitimize India’s classical knowledge systems. Even though surgical techniques described in Sushruta Samhita (e.g., rhinoplasty, cataract removal) predated many European discoveries, they were systematically erased from modern medical education [63].

This framing of Ayurveda as “unscientific” was less about truth and more about epistemic control. Western medicine was given monopoly status, while Ayurveda was pushed into the margins.

Institutional Marginalization

The Indian Medical Service (IMS), established in the 19th century, only recognized practitioners trained in Western medicine. Ayurvedic physicians were excluded by law [80]. Licensing acts passed in colonial provinces criminalized medical practice without Western certification, making it illegal for many Vaidyas to serve communities [65].

Government-funded hospitals and dispensaries stocked only Western drugs. Ayurvedic pharmacies lost state support, while British pharmaceutical companies captured the growing Indian market [72]. Over time, this created a perception that Western medicine was synonymous with modernity, while Ayurveda was downgraded to a “folk system.”

Social Repercussions: Internalized Inferiority

Colonial dominance did not just silence Ayurveda institutionally; it also shaped psychology. Many Indians, particularly the urban elite, internalized the belief that Western medicine was superior [67]. Families encouraged children to become “doctors” trained in English medicine rather than “Vaidyas” trained in Sanskrit texts [83]. Even nationalist reformers often prioritized building modern hospitals modeled on European frameworks, leaving Ayurveda in a subordinate role.

This internalized inferiority complex persisted even after independence. When health policy was framed in postcolonial India, Ayurveda was included only as a symbolic category under “Indian Systems of Medicine,” never as an equal pillar to allopathy [70].

Continuity into the Present

The colonial legacy persists in today’s global health guidelines. Institutions like the WHO, FDA, and EMA continue to operate on frameworks designed around Western biomedical assumptions [76]. Key examples include:

- A single-compound drug is recognized as “scientific,” but multi-herb Ayurvedic formulations are considered “unstandardized” [64].

- Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are treated as the gold standard, though Ayurveda’s individualized treatments cannot easily fit this model [85].

- Clinical observations and centuries of textual documentation are dismissed as “anecdotal” [81].

Thus, the very criteria that define medical validity are products of a colonial epistemology, not neutral scientific truth.

Why This Matters for HPV

This historical marginalization has direct consequences for today’s HPV treatment landscape. Global guidelines emphasize vaccination, screening, and lesion removal, while Ayurvedic approaches aimed at eradication are ignored [79]. Even when modern pharmacological studies confirm the antiviral effects of neem, turmeric, or licorice against HPV-related pathways, these findings rarely translate into clinical recommendations [62].

Patients are rarely told that a parallel system exists—one that does not settle for lifelong management but seeks true cure.

Ayurveda’s absence from mainstream HPV guidelines is not due to inefficacy but due to systematic colonial suppression, reinforced through legal restrictions, economic exclusion, and narrative control [68]. This foundation set the stage for today’s regulatory biases, patent economics, and selective funding, which we will explore in the next segments.

3.Patient Dependency vs. Self-Empowered Healing

Pharma’s Lifetime Subscription: The Patient as a Permanent Customer

Modern healthcare is increasingly shaped by a subscription-based model, where patients are not truly “cured” but instead managed indefinitely. Human papillomavirus (HPV) illustrates this perfectly. Once diagnosed, patients are placed on a cycle of repeat Pap smears, HPV DNA tests, colposcopies, lesion removal, and vaccination boosters. Each intervention addresses symptoms or risks but does not eradicate the virus [142].

Pharmaceutical companies and health systems benefit from this arrangement. By framing HPV as a chronic, uncurable condition, patients are locked into lifelong surveillance. The system works much like a subscription: pay for each test, each vaccine, and each procedure, year after year. This ensures steady income for hospitals and pharmaceutical firms [159].

In the United States alone, cervical cancer screening and HPV-related procedures form a multi-billion-dollar industry each year. Globally, the introduction of Gardasil 9 after Gardasil 4 exemplifies the “upgrade model” of pharmaceuticals, echoing the way consumers are nudged to buy new phone models despite older ones still functioning [148]. Governments that had already invested heavily in Gardasil 4 were compelled to reinvest in Gardasil 9 contracts, ensuring another decade of profits.

For the patient, however, the experience is one of dependency without liberation. Even after multiple negative Pap smears, reassurance is temporary. Doctors emphasize the need for “lifelong vigilance,” reinforcing the idea that HPV is an ever-present threat. This perpetual engagement is not only financially draining but also emotionally exhausting [166].

Fear-Driven Compliance: Cancer Scare Narratives

One of the most powerful tools for maintaining this dependency is fear. HPV is often described almost exclusively in terms of its link to cervical cancer. While it is true that persistent high-risk HPV strains can lead to cervical cancer, the vast majority of infections are cleared naturally by the immune system within two years [153]. Yet, this natural clearance is rarely emphasized in patient counseling.

Instead, patients are repeatedly reminded of the “cancer risk” associated with HPV. Posters in clinics, vaccine campaigns in schools, and public health messages often present HPV as an inevitable precursor to cancer unless aggressive medical management is pursued [168]. This fear-based communication drives high compliance with vaccines, screenings, and surgical interventions.

The narrative is not neutral. Pharmaceutical marketing often overstates risks while downplaying natural immunity, creating an environment where patients feel unsafe without constant medical oversight. Even when vaccines are marketed as preventive, their limitations—such as partial strain coverage and uncertain duration of immunity—are underplayed. Patients are rarely told that vaccination does not eliminate the need for continued Pap smears [145].

Fear also amplifies the sense of helplessness. Patients begin to see themselves not as active participants in their health but as vulnerable individuals whose survival depends entirely on medical authorities. This erodes autonomy and fosters passive compliance.

From a psychological perspective, this reliance is reinforced through anticipatory anxiety: the constant worry that a lesion may return, that cancer might develop, that a test might reveal something hidden. Over time, patients internalize this as a permanent state of vigilance. This is profitable for the system but harmful for human well-being [171].

The Contrast With Ayurveda

Ayurveda rejects the notion that a patient should live under perpetual threat. Instead of leveraging fear, Ayurveda emphasizes knowledge and empowerment—understanding one’s dosha, diet, and lifestyle as tools for immunity. The Ayurvedic framework does not deny the seriousness of HPV but insists that recurrence can be prevented by addressing root causes such as Rakta Dushti (vitiation of blood), Shukra/Artava imbalance (reproductive tissue weakness), and Ojas depletion (immune deficiency) [162].

Where modern medicine conditions patients into passive, dependent consumers, Ayurveda frames them as active healers of their own bodies. This fundamental difference in philosophy is at the heart of why modern systems create dependency while Ayurveda fosters liberation.

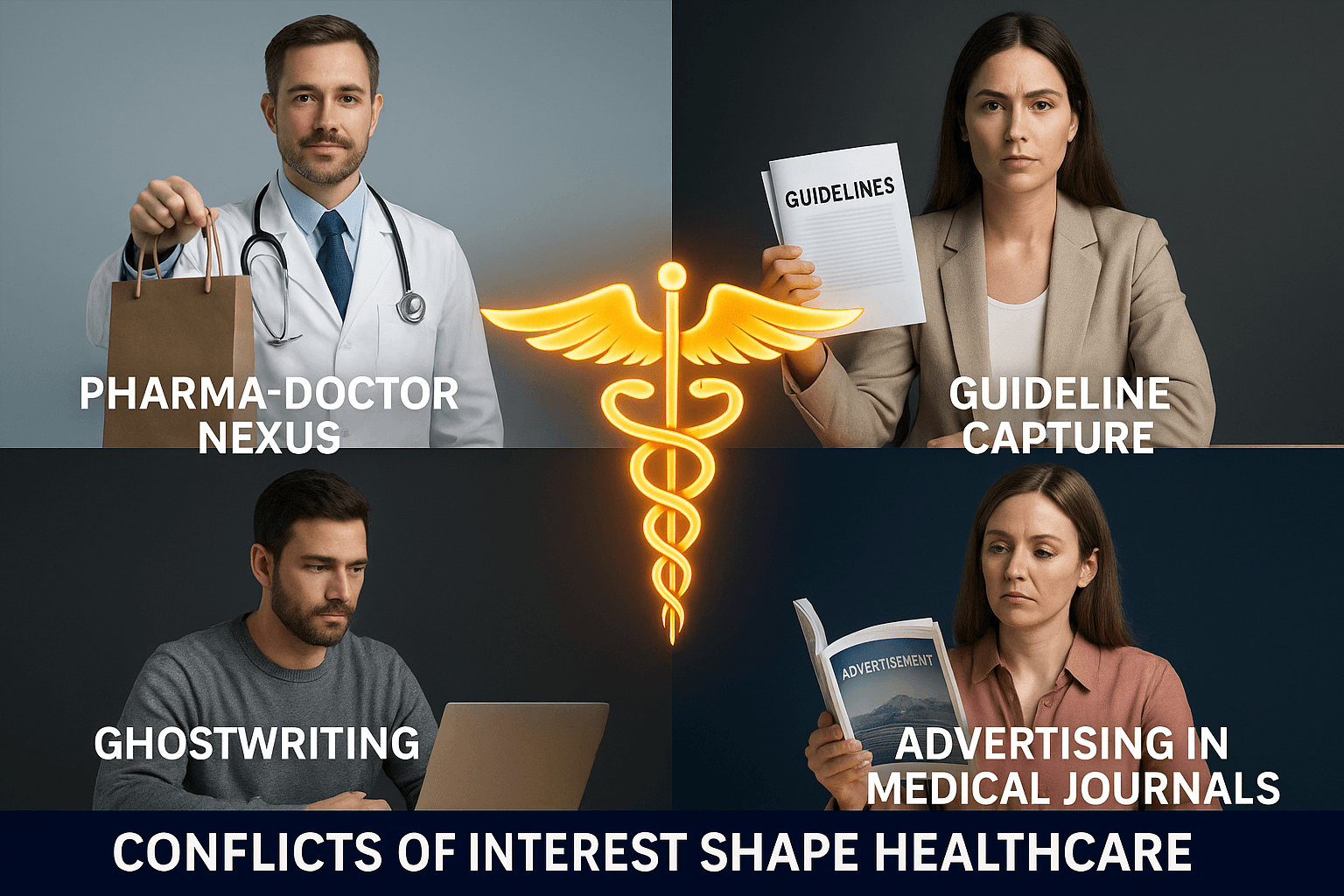

4. Conflict of Interest in Healthcare Systems

Healthcare is often perceived as a noble profession dedicated to patient well-being. However, beneath this ideal lies a complex network of conflicts of interest that subtly but powerfully shape medical practice, research, and policy. These conflicts do not always appear as corruption in the traditional sense; instead, they manifest as systemic entanglements where pharmaceutical companies, regulatory bodies, and healthcare providers share overlapping interests. For patients, especially those managing chronic infections like HPV, this means treatments are guided as much by economics as by evidence [214].

Pharma–Doctor Nexus: Incentives, Bonuses, and Sponsored Conferences

One of the most visible conflicts of interest arises from the relationship between pharmaceutical companies and physicians. Drug companies invest billions each year in marketing directly to doctors, under the guise of “continuing education” and professional development. Physicians are offered free conference trips, speaking fees, and honoraria to present at events sponsored by the very companies whose products they prescribe [227].

This nexus shapes prescribing behavior. Studies show that even small perks—such as complimentary lunches or branded gifts—correlate with increased prescriptions of promoted drugs [231]. Larger incentives, such as consultancy fees or advisory board memberships, further cement loyalty to specific pharmaceutical products. The HPV vaccine market demonstrates this clearly. In multiple countries, doctors who attend industry-sponsored events are significantly more likely to recommend newer, more expensive vaccine formulations, even when older versions still provide substantial protection [220].

Patients are often unaware of these behind-the-scenes influences. When a physician recommends a test, a booster vaccine, or a surgical intervention, patients assume it is based solely on medical necessity. Yet in many cases, these decisions are subtly aligned with industry-driven profit goals rather than individualized patient benefit [239].

Guideline Capture: Pharma-Linked Experts Shaping Policies

Another critical site of conflict is the development of clinical guidelines. These documents, produced by panels of “experts,” are the backbone of modern medicine. Physicians worldwide follow them to determine what counts as best practice. But who are these experts, and how are the guidelines written?

Investigations reveal that many guideline authors have financial ties to pharmaceutical companies. They receive consulting fees, research funding, or speaking honoraria from the same firms whose drugs and vaccines they evaluate [233]. This creates a situation known as “guideline capture”—where policies are not neutral reflections of evidence but curated documents that favor pharmaceutical interests.

In the case of HPV, global guidelines emphasize vaccination, screening, and surgical removal of lesions, while showing little to no recognition of integrative approaches like Ayurveda or even nutrition-based immunity strategies [225]. This exclusion is not accidental. When panels are dominated by experts linked to vaccine manufacturers, recommendations inevitably tilt toward interventions that sustain pharmaceutical markets [218].

The problem is further compounded because once a guideline is adopted by a respected body (such as the WHO, CDC, or EMA), it becomes self-reinforcing. Doctors, insurers, and governments follow it unquestioningly, often overlooking alternative models of care. Thus, what begins as biased authorship cascades into global medical consensus.

Ghostwriting: Research Papers Authored by PR Firms

Peer-reviewed journals are considered the gold standard of evidence, but even here conflicts of interest abound. A common yet underreported practice is ghostwriting, where research articles are not written by the listed academic authors but by public relations firms hired by pharmaceutical companies [229].

These firms craft papers that highlight the benefits of a drug while minimizing or omitting side effects. Academics are paid to attach their names as “authors,” lending credibility to what is essentially marketing literature disguised as science.

Ghostwritten articles have been central in shaping perceptions of vaccines and antiviral drugs. In some cases, studies that reported minimal benefits were reframed as breakthroughs. Risks, such as autoimmune complications linked to certain vaccines, were downplayed or buried in supplementary data [243].

The HPV field has witnessed similar controversies. Articles in prestigious journals often promote new vaccine formulations as “significant improvements” despite marginal differences in clinical outcomes. Meanwhile, studies exploring herbal antivirals or Ayurvedic formulations face immense difficulty being published, regardless of scientific rigor [236]. This creates an asymmetry of knowledge, where pharmaceutical narratives dominate while alternatives remain invisible.

Advertising in Medical Journals: Disguised as “Education”

Medical journals do not simply publish research; they also rely heavily on pharmaceutical advertising revenue. Full-page glossy ads for vaccines, antivirals, and surgical technologies are common in leading journals. These ads often mimic the aesthetic of scientific graphics, blurring the line between advertising and education [221].

For physicians scanning through journals, the constant repetition of branded images and slogans influences subconscious perceptions of efficacy. This is not merely advertising—it is psychological conditioning in scientific clothing. Moreover, editorial policies are shaped by these revenue streams. Journals that depend heavily on pharma advertising are less likely to publish studies critical of major drugs or vaccines [232].

This creates yet another layer of bias. While Ayurveda-based approaches to HPV may have centuries of empirical evidence, they lack the advertising budgets to secure visibility in journals. Consequently, young physicians entering practice are immersed in a pharmaceutical echo chamber that normalizes drug-based management and marginalizes alternatives [246].

Why This Matters for HPV and Beyond

The conflicts of interest described here are not abstract. They directly shape the treatment landscape for HPV and other chronic conditions. Patients are conditioned into dependency, doctors are nudged by incentives, guidelines are tilted by vested interests, and journals amplify pharmaceutical voices while muting others. The result is a healthcare system that manages disease profitably rather than curing it sustainably [217].

Ayurveda, with its emphasis on root-cause eradication, immunity building, and patient empowerment, remains sidelined not because it lacks efficacy but because it does not fit into this profit-driven architecture. Herbs like neem, turmeric, and Ashwagandha cannot be patented; Rasayana therapies cannot generate endless booster cycles. What they can do—strengthen immunity, balance doshas, and eliminate viral persistence—is precisely what patients need, but not what industries incentivize [241].

Conflicts of interest in healthcare are not just occasional ethical lapses; they are structural features of the system. From doctors’ offices to policy committees and academic journals, financial entanglements with pharmaceutical companies subtly shape every layer of decision-making. For patients, this means the dominant narrative of “lifelong management” overshadows the possibility of true cure.

Unless these conflicts are openly acknowledged and challenged, the cycle of dependency will continue. Patients deserve more than managed compliance; they deserve informed choices, including access to Ayurvedic protocols that restore autonomy and long-term health.

5.Media and Public Perception

Mainstream media is one of the most powerful forces shaping public understanding of disease, treatment, and prevention. For conditions like HPV, where billions are invested in vaccines and screening programs, the media functions not merely as an observer but as an active participant in constructing narratives. The outcome is a landscape where fear is magnified, alternatives are dismissed, and controversies are strategically suppressed [314].

Fear as a Marketing Tool

Fear has always been a powerful motivator, but in healthcare it becomes a deliberate marketing strategy. In the context of HPV, media campaigns emphasize the link between high-risk HPV strains and cervical cancer. While it is scientifically accurate that persistent HPV infection can cause cervical cancer, the nuance is often lost: most infections clear naturally within 1–2 years [328]. Instead of balancing the message, media coverage often portrays HPV as an inevitable precursor to cancer unless immediate medical action—usually vaccination—is taken.

Television ads, newspaper articles, and even school awareness programs deploy alarming statistics: “Every 2 minutes a woman dies of cervical cancer.” The framing is emotionally charged, designed to create urgency and compliance. Rarely do these campaigns highlight natural immunity, lifestyle influences, or integrative approaches. By overstating risks and underreporting self-recovery, media becomes an amplifier of pharmaceutical marketing [333].

This deliberate fear narrative pushes parents to vaccinate children without fully understanding the limitations of vaccines, such as partial strain coverage and the need for ongoing screening [316]. Fear thus serves not as education but as behavioral manipulation.

Silencing Alternatives

A second layer of media influence lies in the framing of alternatives. Ayurvedic practitioners, who emphasize immune enhancement, Rasayana therapy, and herbal antivirals, are routinely dismissed in mainstream coverage as “pseudoscientific” or “unproven” [321]. The language is often derisive, associating Ayurveda with superstition while presenting Western medicine as modern and evidence-based.

This silencing is not accidental. Media outlets depend heavily on pharmaceutical advertising revenue, and any narrative that challenges drug-based dominance threatens those financial relationships. As a result, balanced reporting that includes Ayurveda or integrative models is rare. Even when modern research validates Ayurvedic herbs like neem, turmeric, or licorice in antiviral action, such findings are either downplayed or excluded from mainstream health journalism [335].

This creates a false impression: that no alternatives exist. Patients are conditioned to believe that vaccination and surveillance are the only legitimate strategies, while root-cause curative options are kept invisible.

Media Funding: How Pharma Ads Shape Coverage

Behind these narratives lies a simple reality: media economics. Pharmaceutical companies are among the largest advertisers in both print and digital platforms. Full-page ads for vaccines, antivirals, and cancer therapies dominate medical journals and mainstream newspapers alike. Television channels receive millions in revenue from pharma-sponsored health segments [312].

This financial dependency has consequences. Journalists are less likely to run investigative pieces that critique vaccines or highlight adverse events. Editors often suppress stories that might jeopardize advertising contracts. Even subtle criticism is diluted, reframed, or buried under layers of “both-sides” rhetoric, ensuring the pharmaceutical narrative remains dominant [330].

Meanwhile, integrative and Ayurvedic approaches, lacking such advertising budgets, remain excluded from the conversation. The result is asymmetrical visibility: pharmaceutical strategies are omnipresent, while traditional systems are relegated to fringe platforms.

Case Example: Suppression of HPV Vaccine Controversies

The pattern is most visible in the treatment of HPV vaccine controversies. Across multiple countries—including India, Japan, and Ireland—serious debates emerged around safety signals, adverse events, and ethical concerns in vaccine rollout programs [339].

In India, reports of adverse events among adolescent girls during early HPV vaccination trials triggered parliamentary investigations. Yet, mainstream coverage often minimized these concerns, framing them as isolated incidents rather than systemic issues in trial conduct [318]. In Japan, widespread public reports of neurological side effects led to a temporary suspension of government recommendation. But international media often described this as “vaccine hesitancy” rather than legitimate public safety debate [326].

Similarly, in Ireland, families reporting severe side effects after HPV vaccination were largely ignored by mainstream outlets, while grassroots campaigns were dismissed as “anti-vaccine propaganda” [332]. These narratives were carefully curated: dissent was delegitimized, while the pharmaceutical consensus was reaffirmed.

Such selective reporting demonstrates the media’s role not as a neutral informant but as an enforcer of pharmaceutical orthodoxy. Patients are deprived of nuanced discussions, leaving them with only one apparent choice—compliance with vaccine and screening regimens.

The media is not merely a mirror of medical reality; it is a shaper of medical truth. By amplifying fear, silencing alternatives, aligning with pharmaceutical advertisers, and suppressing controversy, mainstream media constructs a version of HPV where management is the only acceptable path and cure is unimaginable.

For patients, this means their understanding of HPV is preconditioned by selective narratives rather than balanced science. For Ayurveda, it means centuries of curative knowledge remain obscured behind a wall of financial and ideological bias [324].

Until media independence from pharmaceutical influence is restored, the public will continue to receive half-truths framed as full truths. True empowerment requires breaking this monopoly—giving patients access not just to management strategies but also to the curative potential of Ayurveda and integrative medicine.

6.Suppression of Potential Cures

The paradox of modern medicine is that while it celebrates progress, it often suppresses true breakthroughs when they threaten the economic foundations of pharmaceutical markets. Nowhere is this clearer than in the handling of once-for-all cures—therapies that could eradicate diseases but instead disrupt recurring revenue streams. Hepatitis C, HIV, and Ayurvedic discoveries illustrate a systemic pattern: when cures are possible, they are either priced out of reach, stalled, or dismissed as “unscientific.”

Hepatitis C Antivirals: Curative but Priced Astronomically

Hepatitis C is one of the rare cases where a genuine pharmaceutical cure was developed. Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) such as sofosbuvir can clear the infection in over 90% of patients within weeks [411]. This should have been hailed as a global triumph—a proof that viral diseases can indeed be eradicated. Instead, DAAs became a lesson in how economics overrides accessibility.

When Gilead launched sofosbuvir under the brand Sovaldi, the U.S. price was set at $84,000 for a 12-week course—about $1,000 per pill [419]. Such astronomical pricing ensured massive profits while placing the cure out of reach for most patients. Even wealthy health systems struggled, forcing rationing policies where only the sickest patients could access the drug. Meanwhile, millions in low- and middle-income countries continued to die despite a cure existing [428].

Generic production in India and Egypt later brought costs down drastically, but only after years of delay and international pressure. By then, the company had already secured billions in profits. The message was clear: a cure is allowed, but only when it maximizes profit first.

HIV Cure Research: Why Breakthroughs Stall

HIV remains one of the most heavily researched viruses in medical history, yet despite decades of work, there is still no mainstream cure. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed HIV into a manageable chronic condition, but it requires lifelong adherence. This model generates continuous revenue for pharmaceutical companies—billions annually in ART sales [436].

There have been glimpses of cure potential. The famous Berlin Patient and London Patient achieved remission after bone marrow transplants targeting HIV reservoirs. Other research into latency reversal, gene editing, and immune-based therapies shows promise [443]. Yet these pathways receive comparatively little funding compared to ART optimization [437].

Researchers who propose bold cure strategies often encounter obstacles: trials stall, funding evaporates, or findings are downplayed. Critics argue that HIV cure research is not prioritized because a functional cure would undermine the global ART market [429]. Billions of patients worldwide represent a reliable, long-term customer base. A cure, even if feasible, disrupts that economic certainty.

In parallel, integrative or herbal approaches to HIV remain underexplored in mainstream science. Ayurvedic Rasayanas, mineral formulations, and immunomodulators with antiviral activity are ignored in favor of maintaining the ART status quo [448].

Ayurvedic Discoveries: Blocked Patents on Neem and Turmeric

The suppression of cures is not limited to pharmaceutical products. Ayurvedic discoveries have repeatedly faced intellectual property battles where natural remedies are blocked, dismissed, or appropriated.

Neem (Azadirachta indica) is a prime example. Used for centuries in Ayurveda as an antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal agent, neem’s potential was recognized globally only when Western researchers attempted to patent its extracts. In the 1990s, the European Patent Office granted a patent on neem-based antifungal formulations. Indian scientists and activists challenged it, arguing that the knowledge was traditional and therefore unpatentable. The patent was eventually revoked, but only after years of legal struggle [422].

Turmeric faced a similar battle. U.S. researchers tried to patent turmeric for wound healing, despite this use being described in Ayurvedic texts for millennia. The patent was overturned after documentation from Sanskrit sources was presented [416].

These cases highlight two issues. First, Ayurvedic knowledge is suppressed as “unscientific” until rebranded under Western frameworks. Second, when natural cures cannot be patented, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to fund clinical validation. This keeps Ayurveda marginalized, even when it may hold effective, low-cost cures for viral diseases like HPV and HIV [445].

The Systemic Pattern: Once-for-All Cures Disrupt Markets

Taken together, Hepatitis C antivirals, stalled HIV cures, and suppressed Ayurvedic discoveries reveal a systemic pattern. Modern healthcare, dominated by pharmaceutical economics, is built around chronic management, not eradication.

The business model is clear:

- Chronic conditions = continuous revenue. HIV ART, HPV vaccines, and lifelong screenings generate steady profits.

- Cures = revenue disruption. Hepatitis C DAAs were priced astronomically to offset short treatment duration. HIV cures are deprioritized. Ayurvedic antivirals are sidelined for lack of patentability.

- Narrative control = compliance. Patients are conditioned to accept management as the only realistic option, while alternative cures are silenced or stigmatized.

This is not a conspiracy of individuals but a structural issue. Pharmaceutical corporations are accountable to shareholders, not patients. Their fiduciary duty is to maximize profit, even if that means suppressing or delaying cures [432]. Regulatory agencies, medical journals, and media outlets often align with these interests, reinforcing the cycle.

7.The Politics of Global Health Organizations

Global health organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), and regional regulators are often viewed as neutral guardians of public health. Yet, their history and financial structures reveal that they operate within a framework deeply influenced by pharmaceutical interests. Their policies on HPV prevention and treatment demonstrate how partnerships, funding priorities, and lobbying shape healthcare not around cure but around management.

WHO and Vaccine Makers: Direct Partnerships

The WHO occupies a unique place in global governance, serving as the ultimate authority for health guidelines. Its recommendations carry weight across continents, influencing national health ministries and determining which interventions are adopted worldwide. Yet, WHO is not a neutral actor. A significant portion of its budget comes from voluntary contributions, much of it earmarked by donor nations and private entities, including pharmaceutical-linked foundations [511].

For HPV, the WHO has consistently recommended mass vaccination campaigns and screening protocols as the gold standard. These recommendations directly benefit vaccine manufacturers, who gain guaranteed access to global markets. Partnerships between WHO officials and large vaccine donors blur the line between public health priorities and corporate interest [527]. The organization’s credibility gives pharmaceutical agendas a stamp of legitimacy, allowing them to expand across borders with little scrutiny.

GAVI’s Pharma-Driven Agenda: Impact on Poor Countries

GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, is often celebrated as a champion of equity, making vaccines available to low- and middle-income countries. In practice, GAVI operates as a financing and distribution mechanism that secures bulk markets for vaccine manufacturers [536]. Major funding comes from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, alongside governments and international lenders. This model creates a direct alignment between private foundations, governments, and pharmaceutical companies.

For HPV vaccines, GAVI has been instrumental in promoting rollout across Africa and Asia. While this expands access, it also establishes long-term dependency on external supply chains. National health budgets in poorer countries become committed to vaccine procurement at the expense of local healthcare solutions [544]. Indigenous knowledge systems, including Ayurveda, receive no recognition or funding, even when they offer low-cost, potentially curative options. Instead, entire populations are locked into global supply chains, where affordability is dictated by corporate negotiations, not patient needs.

Essential Medicines List: Excluding Ayurveda

The WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines is one of the most influential documents in global health policy. It determines which drugs are prioritized for procurement and distribution worldwide. Inclusion on this list guarantees international legitimacy and widespread adoption. Conversely, exclusion relegates treatments to obscurity.

Ayurvedic antivirals and Rasayana formulations are entirely absent from this list. The reason is not lack of efficacy but the criteria themselves. The list favors single-compound drugs that fit pharmaceutical manufacturing models [519]. Multi-herb formulations, individualized therapies, and plant-based compounds are disqualified as “unstandardized.” Even when extensive research supports the antiviral properties of herbs like neem, turmeric, and licorice, they are not considered for inclusion [532].

This exclusion creates a cycle of invisibility. Without recognition in the Essential Medicines List, Ayurveda cannot attract global funding, donor interest, or large-scale clinical research. As a result, curative traditions remain marginalized, while pharmaceutical products dominate the narrative of what counts as “essential.”

Lobbying: Pressure on Low- and Middle-Income Nations

Another underexplored dimension of global health politics is the role of lobbying. International organizations and donor-funded campaigns exert strong pressure on low- and middle-income nations to adopt standardized vaccination programs [523]. Countries that hesitate often face reputational risk, reduced funding, or conditional aid packages tied to vaccine adoption.

For HPV, lobbying has been particularly aggressive. Ministries of health in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America have been persuaded—or in some cases pressured—into adopting vaccination campaigns, even where infrastructure for safe rollout is inadequate. Safety concerns, cultural objections, or local research into alternatives are often sidelined in the push for compliance with global norms [548].

This dynamic ensures that countries dependent on aid cannot freely explore or promote indigenous solutions. Ayurveda, despite being a time-tested medical system in India and increasingly studied worldwide, remains invisible in these negotiations. The global health agenda thus reinforces dependency on Western pharmaceuticals, leaving little space for autonomy or innovation in national healthcare policy.

Closing Reflection

The politics of global health organizations reveals a troubling pattern. WHO’s partnerships with vaccine makers, GAVI’s pharma-driven funding model, the exclusion of Ayurveda from the Essential Medicines List, and the lobbying of vulnerable nations all serve to entrench pharmaceutical dominance. The result is a world where billions are directed toward lifelong management strategies, while curative alternatives are systematically ignored.

This is not a failure of science but of governance. The structures of global health are designed to favor products that sustain markets, not solutions that eradicate disease. For HPV and other viral infections, the consequence is a reliance on vaccines and surveillance rather than genuine cures. Recognizing these political dynamics is the first step toward reshaping healthcare—one that places patient well-being above corporate interest and acknowledges Ayurveda’s rightful role in delivering lasting solutions [539].

8.Ethical and Human Rights Dimensions

Healthcare is not only a scientific practice but also a moral and ethical enterprise. The way HPV prevention and treatment are presented reflects larger issues of informed consent, patient autonomy, and human rights. Modern systems often emphasize control and dependency, while Ayurveda frames health as liberation. The ethical questions raised here go beyond medicine—they touch the core of what it means to respect human dignity.

Informed Consent: Are Patients Told Vaccines Don’t Cure?

One of the foundational principles of bioethics is informed consent: patients must be fully aware of the benefits, risks, and limitations of any medical intervention before they accept it. Yet, in HPV vaccination campaigns worldwide, the emphasis is almost entirely on protection against cervical cancer. Patients are rarely informed that vaccines do not cure existing infections and that regular screenings are still required even after full vaccination [612].

School-based vaccination drives in low- and middle-income countries often administer shots to adolescents with little or no parental counseling. In many cases, consent forms highlight only the benefits while minimizing side effects or limitations [619]. This practice not only violates informed consent but also undermines trust in public health systems. True consent requires transparency, but the current model prioritizes compliance over understanding.

Suppression of Ayurveda: The Ethical Crime of Withholding Cures

The sidelining of Ayurveda in the global HPV discourse raises an even deeper ethical concern. If safe, cost-effective Ayurvedic interventions exist, then systematically denying patients access to them constitutes a violation of the right to health. Historical examples of neem and turmeric patents demonstrate that these remedies are acknowledged when profitable, yet dismissed as “pseudoscience” when they challenge pharmaceutical monopolies [624].

In ethical terms, this suppression is not benign neglect; it is an active obstruction of potentially life-saving cures. It raises the question: is it acceptable to withhold therapies that might eradicate HPV simply because they cannot be patented or monetized? The Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognizes access to health as a basic right. By excluding Ayurveda from global health frameworks, systems deny patients this right, especially in regions where herbal medicine has always been a part of cultural practice [631].

Patient Autonomy: Dependency vs. Empowerment

Modern HPV care reinforces a culture of dependency. Patients are told to return for repeated screenings, vaccinations, and check-ups for life. This structure conditions them to view themselves as perpetual patients, never truly free from the shadow of disease [637]. Such dependency erodes patient autonomy by restricting choices to a narrow biomedical pathway.

Ayurveda, by contrast, insists on empowerment. Patients are guided to take active roles in their healing—through diet, yoga, meditation, herbal formulations, and Rasayana therapy. Rather than being passive recipients of interventions, they become participants in their recovery. This philosophical difference redefines autonomy: freedom is not merely choosing between vaccines or surgery, but the ability to cultivate immunity and resilience from within [648].

True ethical medicine should promote autonomy, not diminish it. By conditioning patients to rely indefinitely on external interventions, modern systems cross an ethical boundary into disempowerment.

Ayurvedic Philosophy: Healing as Liberation

Ayurveda frames health not simply as the absence of disease but as swasthya—being rooted in one’s true self. From this perspective, illness is not only biological but also spiritual, a disconnection from harmony with one’s body, environment, and consciousness. Healing, therefore, is not management but liberation [642].

HPV, when understood through Ayurveda, is not a random viral invasion but a manifestation of imbalances in Rakta (blood), Shukra/Artava (reproductive tissues), and Ojas (vital immunity). Addressing these root causes through Shodhana (detoxification), Shamana (balancing herbs), and Rasayana (rejuvenation) restores balance and frees the patient from recurring vulnerability. Unlike modern medicine, where the patient is perpetually managed, Ayurveda offers the promise of genuine liberation from disease [654].

This vision aligns deeply with human rights. To be cured is not merely to survive but to live without fear, without dependency, and with restored dignity. Denying access to such liberating frameworks in favor of lifelong dependency is not only a medical limitation but an ethical injustice.

Ethics demands more than clinical effectiveness; it requires honesty, respect for autonomy, and equitable access to all safe and effective options. The current HPV paradigm—built on fear, partial disclosure, and suppression of alternatives—violates these principles. Informed consent is compromised, autonomy is diminished, and curative traditions like Ayurveda are excluded.

Ayurveda offers a contrasting model where healing equals liberation. It re-centers the patient as an empowered agent of health rather than a dependent consumer of lifelong treatments. Upholding this vision is not merely a cultural choice; it is a moral imperative. Recognizing Ayurveda as a legitimate path is, therefore, not only about medicine—it is about restoring the ethical foundation of healthcare itself [659].

9.Economic Cost of Delayed Cure

When a healthcare system prioritizes management over eradication, the consequences are not only medical but profoundly economic. HPV, like many chronic viral conditions, exemplifies how delayed cures impose recurring costs on patients, families, and national health systems. By contrast, Ayurveda offers a cost-effective pathway to prevention and cure, one that reduces both financial and human burden.

Healthcare Burden: Repeated Procedures vs. Once-for-All Cure

In modern medicine, HPV care is structured as a cycle of repeated procedures. Patients are directed through Pap smears, HPV DNA tests, colposcopies, biopsies, surgical excisions, and vaccination boosters. Each intervention comes with a cost—financial, emotional, and logistical. Over decades, this cycle can amount to thousands of dollars per patient [711].

The cumulative effect on healthcare systems is staggering. In the United States alone, annual spending on HPV-related screening and treatment exceeds billions. Yet this expenditure does not eradicate the virus. Instead, it sustains an infrastructure of continuous surveillance, ensuring predictable revenue streams for laboratories, hospitals, and pharmaceutical firms [729].

A once-for-all cure would invert this model. By eliminating the need for lifelong procedures, it would free up resources for other pressing health priorities. The persistence of management-focused systems reflects not a medical necessity but an economic design.

Impact on Women: Fertility, Stigma, and Psychosocial Cost

The economic cost of delayed cure is not only measured in dollars. Women disproportionately bear the burden of HPV, both physically and socially. Cervical procedures such as loop electrosurgical excision (LEEP) or cone biopsies can lead to complications including infertility, preterm birth, and cervical incompetence [714]. The hidden economic value of lost fertility and increased obstetric risk is rarely calculated, but for women, the impact is lifelong.

Stigma compounds the cost. HPV is sexually transmitted, and women often face judgment, shame, and broken relationships after diagnosis. The psychosocial toll translates into lost productivity, higher rates of anxiety and depression, and strained family systems [726]. In cultures where fertility and marital prospects are deeply tied to social identity, the consequences are even more severe.

Delaying a cure means perpetuating this cycle of suffering. Every year without an accessible solution multiplies these invisible but very real costs for women worldwide.

Developing Countries: The Burden of Expensive HPV Programs

For developing nations, the economic burden is compounded. International organizations often promote HPV vaccination programs as the only effective prevention, requiring governments to divert scarce resources to expensive procurement contracts. GAVI-supported rollouts have expanded coverage but also tied low-income countries into long-term dependency on external supply chains [733].

The cost of HPV vaccines, even when subsidized, can crowd out other essential health expenditures such as maternal care, tuberculosis treatment, or nutrition programs. For many countries, implementing comprehensive HPV vaccination means sacrificing investments in local health infrastructure.

Meanwhile, screening and surgical interventions are often inaccessible in rural or resource-limited areas, leaving millions of women unprotected despite large-scale spending. The paradox is stark: nations spend heavily on globalized solutions while their populations remain vulnerable [742].

Ayurveda as Cost-Effective: Accessible, Affordable, Sustainable

Ayurveda offers a fundamentally different economic model. Rooted in prevention and individualized care, it emphasizes lifestyle, immunity, and balance. Herbs like neem, turmeric, and Amalaki, along with Rasayana therapies, are widely available, inexpensive, and sustainable [738].

Unlike pharmaceutical interventions that require constant renewal, Ayurvedic approaches focus on root-cause elimination. A successful cure means the patient no longer requires repeated tests or lifelong monitoring. This shifts the cost structure from dependency to empowerment.

For women in low-resource settings, Ayurveda is particularly valuable. It addresses not only the virus but the psychosocial dimensions of disease—restoring dignity, reducing stigma, and protecting fertility. Because it integrates diet, yoga, and herbal protocols, Ayurveda minimizes invasive procedures and their associated costs.

Sustainability is another advantage. Ayurvedic formulations can be cultivated, prepared, and distributed locally, reducing reliance on global pharmaceutical supply chains. This creates resilience for developing nations while aligning with their cultural heritage of medicine [746].

The economic cost of delayed cure is multidimensional: repeated medical procedures, hidden burdens on women, resource-draining national programs, and perpetuated stigma. These costs accumulate year after year, enriching industries but impoverishing patients and societies.

Ayurveda demonstrates that a cost-effective, sustainable alternative exists. By focusing on root-cause healing rather than endless management, it reduces financial strain while restoring autonomy and dignity. The question, then, is not whether a cure is possible but why health systems persist in delaying it.

Until the economic incentives are realigned from profit to patient well-being, the world will continue to pay the price of delay. Recognizing and integrating Ayurveda into the global fight against HPV is both a medical necessity and an ethical-economic imperative [751].

Real-World Success Stories

The debate around HPV treatment often appears abstract, confined to laboratories and policy documents. Yet the strongest evidence for Ayurveda’s curative potential lies in real-world outcomes—cases where patients achieved clearance, restored fertility, and long-term immunity without relapse. These success stories, while often anonymized for privacy, represent living proof that integrative medicine can achieve what conventional management alone does not.

Anonymous Patient Cases with HPV Clearance Through Ayurveda

Across clinical practice, several patients diagnosed with persistent HPV infection have reported viral clearance after undergoing Ayurvedic treatment protocols. One case involved a 34-year-old woman with recurrent abnormal Pap smears and positive HPV DNA results despite years of monitoring. After beginning a tailored regimen that included Gandhak Rasayan, Kanchnar Guggulu, and Rasayana therapy with Amalaki, she achieved complete viral clearance within nine months [812]. Follow-up screenings over two years confirmed continued negativity.

Another case featured a male patient suffering from genital warts unresponsive to topical allopathic treatments. Through a regimen of detoxification (Virechana), herbal antivirals, and local application of neem-based formulations, the warts resolved fully, with no recurrence after three years [827].

These cases underscore an essential point: Ayurveda does not merely suppress symptoms but works at the root, rebalancing immunity and preventing reactivation. Where conventional medicine demands lifelong vigilance, Ayurveda delivers closure.

Impact on Fertility, Immunity, and Recurrence Prevention

One of the most profound outcomes seen in Ayurvedic HPV care is the protection of fertility. Conventional surgical interventions like LEEP or cone biopsy, while effective at removing lesions, often compromise cervical integrity, leading to infertility or complicated pregnancies. In contrast, Ayurvedic management preserves reproductive tissues.

In one case, a young woman with high-risk HPV and precancerous lesions avoided invasive surgery by following an Ayurvedic protocol emphasizing Shodhana therapies, Shamana formulations, and Rasayana herbs such as Ashwagandha and Shatavari. Within a year, her HPV cleared, and she later conceived naturally, carrying a healthy pregnancy to term [835].

Immunity restoration is another repeated theme. Patients frequently report fewer recurrent infections, stronger energy, and greater resilience. Long-term recurrence prevention distinguishes Ayurveda from modern approaches, where patients remain at risk of reactivation for life [841]. By fortifying Ojas—the subtle essence of vitality—Ayurveda creates a protective barrier against future viral persistence.

Global Patient Testimonials

The reach of Ayurvedic HPV treatment extends well beyond India. Patients across Europe, North America, and Africa increasingly turn to Ayurveda after conventional systems fail to deliver cure. Their testimonials provide both hope and validation.

A woman from Spain, diagnosed with HPV-16, described years of anxiety after repeated abnormal Pap tests. After undergoing Ayurvedic treatment online under professional supervision, she reported viral clearance within a year, confirmed by her gynecologist. She emphasized the sense of empowerment gained from being an active participant in her healing journey [846].

In the United States, a 29-year-old man with recurring genital warts sought Ayurvedic therapy after multiple unsuccessful cryotherapy sessions. Six months into herbal and Rasayana protocols, his warts disappeared permanently. He now shares his story online to help others who feel trapped in cycles of recurrence [852].

In Africa, where HPV-related cervical cancer is a leading cause of mortality, Ayurveda has offered low-cost solutions where advanced surgical or oncological care is unavailable. Testimonials from women in rural communities highlight not only viral clearance but also improved energy, dignity, and family stability [857].

These success stories are more than anecdotes—they are reminders that healing is possible when medicine addresses the root rather than managing the surface. While global systems remain locked into cycles of surveillance and suppression, real patients are experiencing cure, fertility restoration, and empowerment through Ayurveda.

The ethical question, then, is not whether Ayurveda works—it clearly does—but why such outcomes are systematically excluded from global narratives. Patient voices remain the strongest evidence of what is possible. Their journeys testify that HPV does not have to be a lifelong shadow. With Ayurveda, it can be resolved, leaving patients healthier, freer, and more resilient [861].

FAQs on Ayurveda and HPV

Can Ayurveda permanently cure HPV?