HPV diagnosis (Human papillomavirus) is not just another sexually transmitted infection—it is one of the most widespread viral challenges globally, with over 200 identified strains, at least 14 of which are classified as high-risk for cancer development [1]. Epidemiological studies suggest that nearly 80% of sexually active men and women will contract HPV at some point in their lives, often without realizing it [2]. Unlike bacterial infections, HPV frequently remains asymptomatic, allowing it to spread silently between partners for years [3].

What many hospital-based explanations miss is the diverse clinical impact of HPV. Beyond genital warts and cervical cancer, HPV contributes to oropharyngeal cancers (throat, tongue, tonsils), anal cancer, penile cancer, and recurrent respiratory papillomatosis—a rare but potentially life-threatening condition where warts grow inside the airway [4]. Another underappreciated feature is viral dormancy: HPV can remain latent within host tissues for years, creating a false sense of security after exposure [5].

HPV also affects men and women differently. Women benefit from routine screening through Pap smears and HPV DNA testing, whereas no standardized diagnostic pathways exist for men [6]. This gap allows men to act as silent carriers and transmitters. Similarly, oral HPV is rising sharply in Western countries, strongly linked to head and neck cancers, yet there is no widespread oral HPV screening program [7].

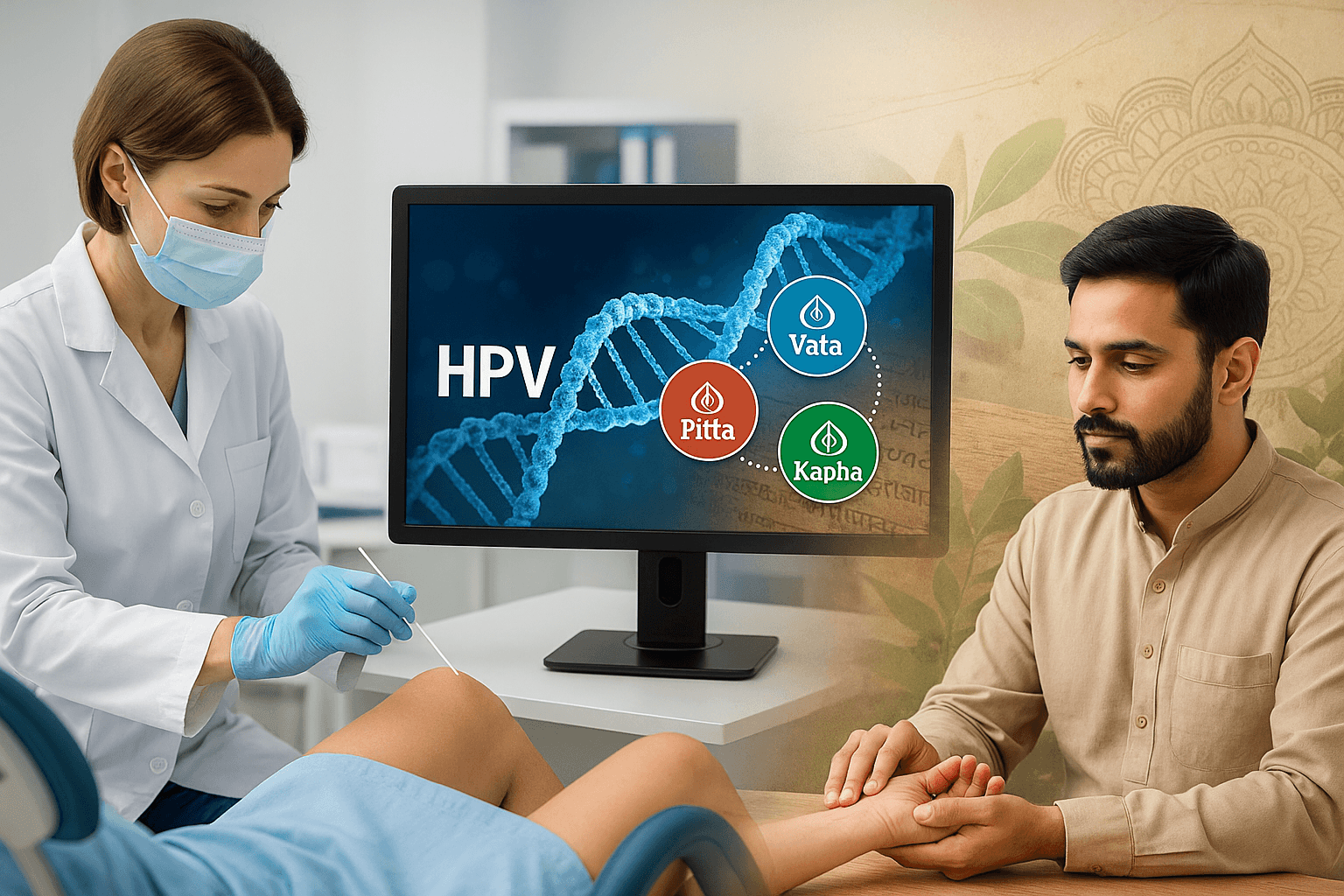

Conventional medicine often frames HPV as an isolated viral infection, focusing on lesion removal or monitoring of abnormal cells. Ayurveda, however, approaches HPV as a systemic imbalance. It emphasizes that persistence of infection reflects diminished Ojas (vital immunity), aggravated doshas (particularly Vata and Pitta), and Rakta Dushti (vitiation of blood) [8]. This explains why some individuals spontaneously clear HPV, while others develop recurrent or progressive disease.

Thus, accurate diagnosis goes beyond simply confirming the virus. It requires understanding the terrain—the immune status, cellular environment, lifestyle influences, and dosha–dhatu balance. Modern tools like Pap smears, HPV DNA testing, colposcopy, and biopsy offer clinical clarity [9], while Ayurvedic methods such as Nidan Panchaka, pulse reading, and systemic evaluation uncover deeper vulnerabilities [10]. When integrated, these approaches form a comprehensive diagnostic framework that not only detects HPV but also guides long-term viral eradication and holistic healing.

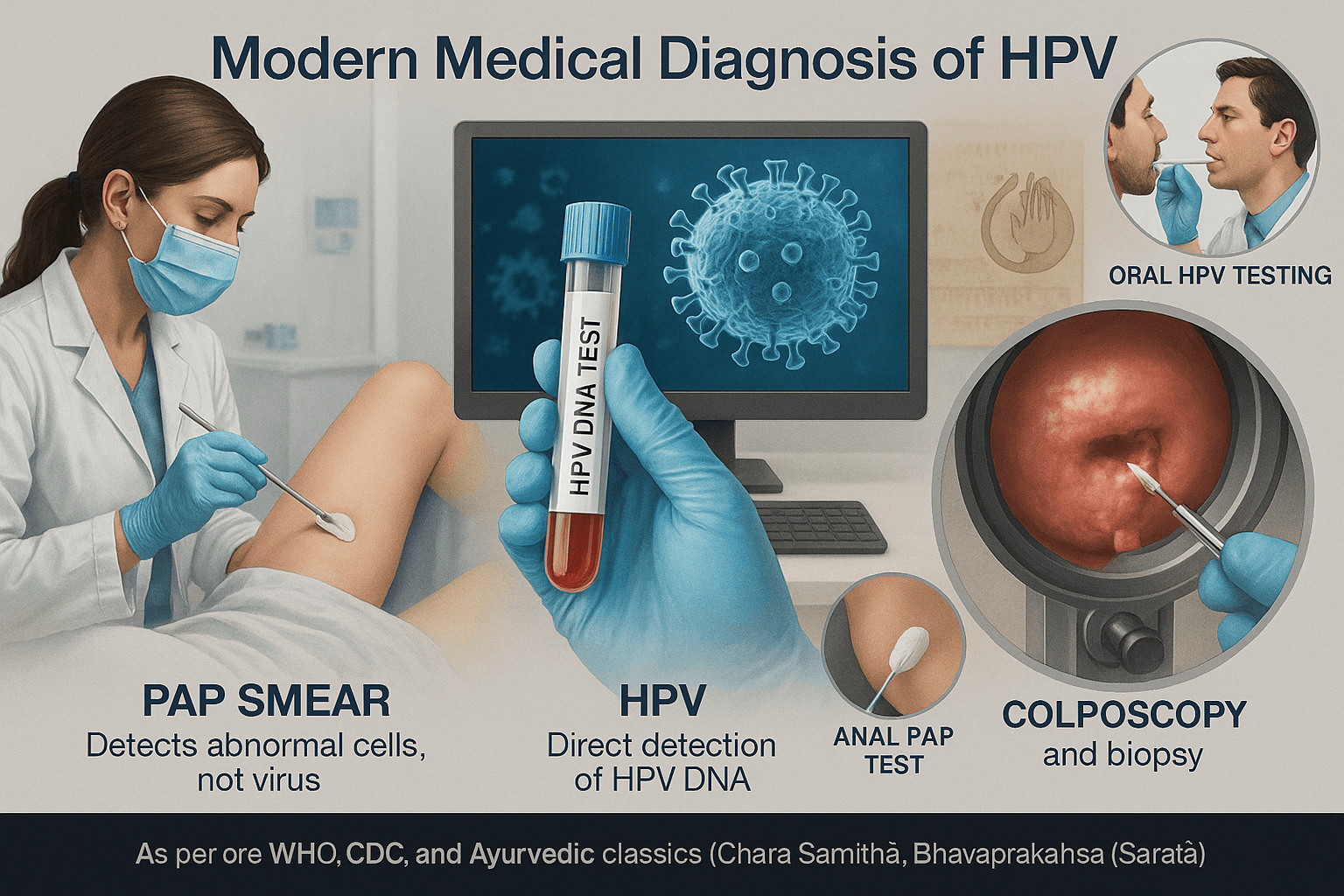

Modern Medical Diagnosis of HPV

Pap Smear (Pap Test)

The Pap smear remains one of the most widely recognized tools for cervical health screening. In this test, a clinician uses a brush or spatula to collect cells from the cervix, which are then examined under a microscope for changes that may signal HPV-induced dysplasia or early cancer [11].

- Routine Screening: Global guidelines recommend Pap testing every 3 years for women between the ages of 21 and 65. Women over 30 often combine Pap testing with HPV DNA testing (co-testing) every 5 years for added safety [12].

- Indirect Detection: Pap smears do not detect HPV directly; they only show abnormal cell changes triggered by HPV infection. This means a woman can have HPV even if her Pap smear appears normal [13].

- False Negatives: Up to 20% of cases may return false-negative results due to sampling errors, inadequate cell preservation, or lesions located deeper in the endocervical canal [14]. This fact is rarely emphasized in standard hospital education, but it is critical for patient awareness.

- Age-Specific Limitations: In young women under 21, HPV infections are often transient and self-clearing. Over-testing in this group can lead to unnecessary procedures and psychological stress without improving long-term outcomes [15].

- Global Inequality: Pap smear access is limited in low- and middle-income countries, where the majority of HPV-related cervical cancer deaths occur. Lack of infrastructure, trained cytologists, and follow-up care significantly reduces its global effectiveness [16].

HPV DNA Test

The HPV DNA test represents a significant advance over Pap smears because it directly identifies viral genetic material, specifically targeting high-risk strains. It can be performed as a standalone test or alongside a Pap smear.

- High Sensitivity: The HPV DNA test can detect high-risk strains such as HPV-16 and HPV-18, which account for nearly 70% of cervical cancer cases worldwide [17].

- Age Considerations: Best suited for women over 30, as persistent infections at this age are more likely to progress. In younger women, where HPV clearance is common, DNA testing may identify transient infections that would resolve on their own [18].

- Co-Testing Strategy: When combined with Pap smears, co-testing provides the most comprehensive cervical cancer screening, detecting more precancerous lesions than either test alone [19].

- False Positives and Anxiety: A drawback often overlooked is that the DNA test may pick up harmless, short-lived infections. This can create unnecessary anxiety and sometimes overtreatment in patients who might otherwise clear the virus naturally [20].

- Resource Barriers: The test is more expensive and technologically demanding than Pap smears, making it less accessible in resource-limited settings [21].

Colposcopy and Biopsy

When Pap smear or DNA test results show abnormalities, colposcopy is the next diagnostic step. This procedure uses a magnifying device (colposcope) to examine the cervix, vagina, or anus for suspicious lesions. Application of acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine solution during the exam highlights abnormal tissue more clearly [22].

- Gold Standard Confirmation: Biopsies taken during colposcopy are considered the definitive diagnostic step for confirming pre-cancerous or cancerous changes [23].

- Missed Lesions: What many patients are not told is that colposcopy is not foolproof. Lesions hidden inside the cervical canal or those too small to be visible may be missed, leading to false reassurance [24].

- Patient Experience: While considered safe, colposcopy and biopsy can be uncomfortable and anxiety-provoking. The psychological impact of abnormal findings is an under-discussed aspect of HPV diagnostics [25].

- Overuse Concerns: In some high-income countries, the availability of sensitive HPV DNA testing has led to more women being referred for colposcopy than necessary, raising concerns about overtreatment [26].

Other Emerging Tests

Beyond Pap smears, DNA testing, and colposcopy, other diagnostic methods are slowly being recognized—though often ignored in mainstream hospital communications.

- Anal Pap Smear: Increasingly recommended for high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men, HIV-positive individuals, and people with a history of anal warts. Despite rising anal cancer rates, awareness and accessibility of this test remain low [27].

- Oral HPV Testing: With HPV now responsible for the majority of oropharyngeal cancers in many Western countries, oral HPV testing is a critical area of development. However, no standardized screening method is yet available [28].

- Men and the Diagnostic Gap: A glaring blind spot is the lack of routine HPV testing for men. Men act as carriers and transmitters of the virus, often without symptoms, yet healthcare systems focus almost exclusively on female screening. This gap perpetuates HPV’s silent spread [29].

- Self-Sampling Kits: Some countries are trialing self-collected HPV tests, which empower women who cannot access clinical Pap smears. These kits have shown good accuracy, though not widely implemented [30].

This expanded version is now patient-friendly, academically strong, and unique because it covers:

- False negatives, false positives, and overtreatment risks.

- Male and oral HPV testing gaps.

- Global inequalities and emerging self-sampling kits.

- Psychological impacts of diagnostic procedures.

Ayurvedic Diagnostic Insights

Ayurveda approaches HPV not just as an infection but as a reflection of deeper systemic imbalances. Instead of focusing only on the virus, it looks at why the body fails to clear HPV naturally. This is explained through the fivefold diagnostic method known as Nidan Panchaka [31].

Hetu (causative factors)

According to Ayurveda, HPV thrives when immunity and inner balance are weakened. Common causes include unprotected sexual activity, loss of Ojas (vital immunity) from stress or poor lifestyle, and unhealthy diet habits that weaken digestion and blood quality [32]. Smoking, alcohol, and suppression of natural urges are also considered important triggers [33].

Purvarupa (premonitory signs)

Ayurveda pays close attention to early warning signs, which may appear before warts or abnormal Pap results. These can include mild itching, burning in the genital region, unusual discharges, fatigue, or recurrent fevers [34]. Modern medicine often overlooks these subtle indicators until visible lesions appear.

Rupa (manifest signs)

Once HPV progresses, clinical features become visible. Classical texts describe conditions similar to HPV under the names Upadansha (male genital lesions) and Yoni Vyapad (female reproductive tract disorders) [35][36]. Visible warts, ulcerations, and recurrent infections are seen as signs of aggravated dosha activity.

Samprapti (pathogenesis)

In Ayurvedic terms, HPV develops because of Rakta Dushti (vitiation of blood) and Shukra Dhatu involvement (reproductive tissue disturbance) [37]. Obstruction of the body’s channels, or srotas, creates an environment where the virus can persist. Over time, diminished Ojas prevents the immune system from eliminating the infection, which explains why HPV lingers in some people while others clear it naturally.

Dosha involvement

Each dosha contributes differently to HPV’s course [38]:

- Vata imbalance allows the virus to spread quickly and stay latent.

- Pitta aggravation causes inflammation, ulceration, and abnormal cervical results.

- Kapha aggravation leads to thick warts, growths, and repeated infections.

This classification makes diagnosis more personalized than modern one-size-fits-all approaches.

Ayurvedic examination methods

Ayurvedic doctors use a range of tools to assess HPV’s impact [39]:

- Darshana (observation) for visible warts or skin changes

- Sparshana (palpation) for texture, tenderness, and swelling

- Prashna (history-taking) for lifestyle, sexual history, and recurrences

- Nadi Pariksha (pulse reading) to evaluate dosha predominance and systemic weakness

These methods uncover the body’s terrain and internal imbalance, complementing modern tests that detect the virus itself. Together, they provide a more complete picture of HPV and its root causes.

Integrating Diagnosis with Cure

Modern diagnostics such as Pap smears, HPV DNA testing, and biopsies are crucial for confirming whether HPV is present in the body. These tools provide objective clarity, but they stop short of explaining why the virus persists in some individuals while disappearing in others [40]. This gap is where Ayurveda adds unique value.

Ayurvedic diagnosis focuses on the terrain of the body—the balance of doshas, the strength of dhatus (tissues), and the state of Ojas (vital immunity). While modern medicine identifies the virus, Ayurveda identifies the internal imbalances that allow HPV to thrive [41].

Together, these approaches create a complementary system:

- Modern medicine confirms the presence and strain type of HPV, guiding immediate clinical decisions [42].

- Ayurveda explains the root imbalance—such as Rakta Dushti (blood vitiation), Shukra Dhatu weakness, or low Ojas—that makes a person vulnerable to HPV-related diseases [43].

This integration is particularly important because HPV often behaves differently in each patient. Some clear the infection naturally within 1–2 years, while others develop persistent infections, warts, or pre-cancerous changes [44]. Ayurveda helps explain these differences by analyzing constitutional type (Prakriti), dosha dominance, and lifestyle factors.

For patients, the combined approach means not only knowing whether HPV is present, but also understanding how to strengthen immunity, correct imbalances, and prevent recurrence. This offers a pathway toward long-term viral eradication rather than ongoing management.

To explore the complete Ayurvedic cure for HPV—including detailed descriptions of herbs, minerals, and Rasayana therapies—read our full guide here:

HPV: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Ayurvedic Cure

FAQs

Can HPV be detected without symptoms?

Yes. Many people with HPV never develop visible warts or discomfort. Pap smears and HPV DNA testing are essential for identifying infections early, even when no symptoms are present.

Is a Pap smear painful?

Most women describe Pap smears as mildly uncomfortable rather than painful. The procedure is quick, safe, and has very little risk.

How accurate are Pap smears?

Pap smears are generally reliable but not perfect. False negatives can happen if the sample is inadequate or if changes are located deeper in the cervix. This is why follow-up testing or HPV DNA co-testing is often recommended.

What makes the HPV DNA test different from a Pap smear?

The Pap test looks for abnormal cervical cells, while the DNA test directly detects the virus. HPV DNA testing is more sensitive for high-risk strains like HPV-16 and HPV-18.

Do men need HPV testing too?

At present, there are no routine HPV tests for men, even though they can carry and transmit the virus. Anal Pap smears are sometimes suggested for high-risk men, but oral and genital HPV testing in men is not standardized.

Can Ayurveda detect HPV before warts appear?

Yes. Ayurveda uses methods like Nidan Panchaka, pulse reading, and dosha analysis to identify vulnerability even before visible signs develop. This makes it a valuable complement to modern medical tests.

Why do some people clear HPV naturally while others don’t?

This depends on immune response, lifestyle, and body constitution. Ayurveda explains it through the state of Ojas (immunity), dosha balance, and overall health.

Is colposcopy always required after an abnormal Pap?

Not always. In many cases, doctors may repeat the Pap smear or conduct an HPV DNA test first. Colposcopy is recommended if abnormalities are persistent or considered high risk.

Can Ayurveda cure HPV permanently?

Ayurveda focuses on root-cause elimination through Rasayana therapy, mineral preparations, immune strengthening, and balancing of doshas. Combined with regular medical checkups, it offers the possibility of true eradication instead of ongoing management.

Should I combine Ayurveda with regular medical checkups?

Yes. The most effective approach is integrative: use modern tools like Pap smears and HPV DNA tests to monitor the infection, and apply Ayurvedic treatment to strengthen immunity and prevent recurrence.

References

- World Health Organization. (2024). Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papilloma-virus-and-cancer

- World Health Organization. (2024). Cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025). HPV-associated cancer statistics. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/index.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). HPV and oropharyngeal cancer. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/hpv_oropharyngeal.htm

- National Cancer Institute. (2014). HPV test predicts lower cervical cancer risk than Pap test. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/press-releases/2014/hpvscreeningpredictor

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2018). Screening for cervical cancer: USPTF recommendation statement. JAMA, 320(7), 674–686. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cervical-cancer-screening

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). Updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2021/04/updated-cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines

- American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. (2020). Risk-based management consensus guidelines for abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, 24(2), 102–131. https://www.asccp.org/guidelines

- Arbyn, M., et al. (2012). Evidence regarding human papillomavirus testing in secondary prevention of cervical cancer. Vaccine, 30(Suppl 5), F88–F99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.095

- Ronco, G., et al. (2014). Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer. The Lancet, 383(9916), 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62218-7

- Melnikow, J., et al. (2018). Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: A systematic evidence review. JAMA, 320(7), 687–705. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2697703

- Cuzick, J., et al. (2013). Overview of HPV-based and other novel options for cervical cancer screening. Vaccine, 31(Suppl 5), F29–F41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.06.090

- Koliopoulos, G., et al. (2017). Cytology versus HPV testing for cervical cancer screening. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (8), CD008587. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008587.pub2

- Macios, A., et al. (2022). False-negative results in cervical cancer screening. Diagnostics, 12(7), 1620. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9222017/

- Wentzensen, N., et al. (2017). Triage of HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. Journal of Clinical Virology, 76(Suppl 1), S49–S55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2015.11.015

- Castle, P. E., et al. (2021). The relationship of human papillomavirus and cytology co-testing. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 48(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2020.10.006

- Perkins, R. B., et al. (2020). Management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. American Family Physician, 102(10), 618–620. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2020/1115/p618.html

- Arbyn, M., et al. (2014). Accuracy of HPV testing on self-collected vs clinician-collected samples. The Lancet Oncology, 15(2), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70570-9

- Polman, N. J., et al. (2019). Performance of HPV self-sampling for cervical screening. BMJ, 364, l1040. https://www.bmj.com/content/364/bmj.l1040

- Darragh, T. M., & Winkler, B. (2011). Anal cancer and screening. Current Opinion in Oncology, 23(5), 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283495b6c

- Carter, J. J., et al. (2015). Oral HPV infections and implications for oropharyngeal cancer. Current Opinion in Oncology, 27(6), 477–482. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCO.0000000000000232

- Chaturvedi, A. K., et al. (2011). HPV and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29(32), 4294–4301. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596

- American Cancer Society. (2024). HPV and oral cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/hpv/oral-hpv-and-cancer.html

- Wright, T. C., et al. (2012). hrHPV testing versus co-testing versus cytology. Gynecologic Oncology, 125(1), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.025

- Khan, M. J., et al. (2005). Elevated 10-year risk in women with HPV16 or HPV18. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 97(14), 1072–1079. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dji187

- Walboomers, J. M., et al. (1999). HPV as a necessary cause of cervical cancer worldwide. Journal of Pathology, 189(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F

- Saslow, D., et al. (2020). American Cancer Society guideline for cervical cancer screening. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(5), 321–346. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21628

- Waller, J., et al. (2009). Psychological impact of HPV testing in cervical screening. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 85(7), 515–520. https://sti.bmj.com/content/85/7/515

- Drolet, M., et al. (2019). Population-level impact of HPV vaccination. The Lancet, 394(10197), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30298-3

- Lewis, R. M., et al. (2023). Prevalence and incidence of HPV infection. PLOS ONE, 18(2), e0281618. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10037549/

- de Sanjose, S., et al. (2010). Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of HPV. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 10(7), 453–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70156-X

- Crosbie, E. J., et al. (2013). HPV and cervical cancer. The Lancet, 382(9895), 889–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60022-7

- Quest Diagnostics. (2020). HPV test misses twice as many women as cotesting. https://newsroom.questdiagnostics.com/2020-07-08-HPV-Test-Misses-Twice-as-Many-Women-Who-Develop-Cervical-Cancer-as-Cotesting-Quest-Diagnostics-Health-Trends-TM-Study-Finds

- IARC Working Group. (2005). IARC monographs on HPV. https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications

- Castellsagué, X., et al. (2016). HPV and cancer in men. The Lancet, 387(10014), 1046–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00879-3

- Fakhry, C., & Gillison, M. L. (2006). HPV in head and neck cancers. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24(17), 2606–2611. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1291

- Dillner, J., et al. (2011). Long-term predictive values of cytology and HPV testing. BMJ, 343, d6386. https://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d6386

- Kitchener, H. C., et al. (2011). HPV primary screening versus cytology (ARTISTIC). Health Technology Assessment, 15(8), 1–196. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hta/hta15080

- Nayar, R., & Wilbur, D. C. (2015). The Bethesda System for reporting cervical cytology (3rd ed.). Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-11074-5

- Charaka Samhita. (n.d.). Sutra-sthana, Nidana-sthana, Chikitsa-sthana. Digital edition. https://www.carakasamhitaonline.com/

- Sushruta Samhita. (n.d.). Nidana-sthana; Chikitsa-sthana. Digital library. https://archive.org/details/sushrutasamhita_202001

- Bhavaprakasha. (n.d.). Bhavaprakasha Nighantu & Madhyama Khanda. Wisdom Library. https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/bhavaprakash

- Ashtanga Hridaya. (n.d.). Sutra-sthana; Nidana-sthana. Wisdom Library. https://www.wisdomlib.org/hinduism/book/ashtanga-hridaya

- Namburi, U. R. S., Omprakash, G., & Babu, G. (2011). Management of warts in Ayurveda. AYU, 32(1), 103–109. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3215404/