- Types of Breast Cancer

- Risk Factors

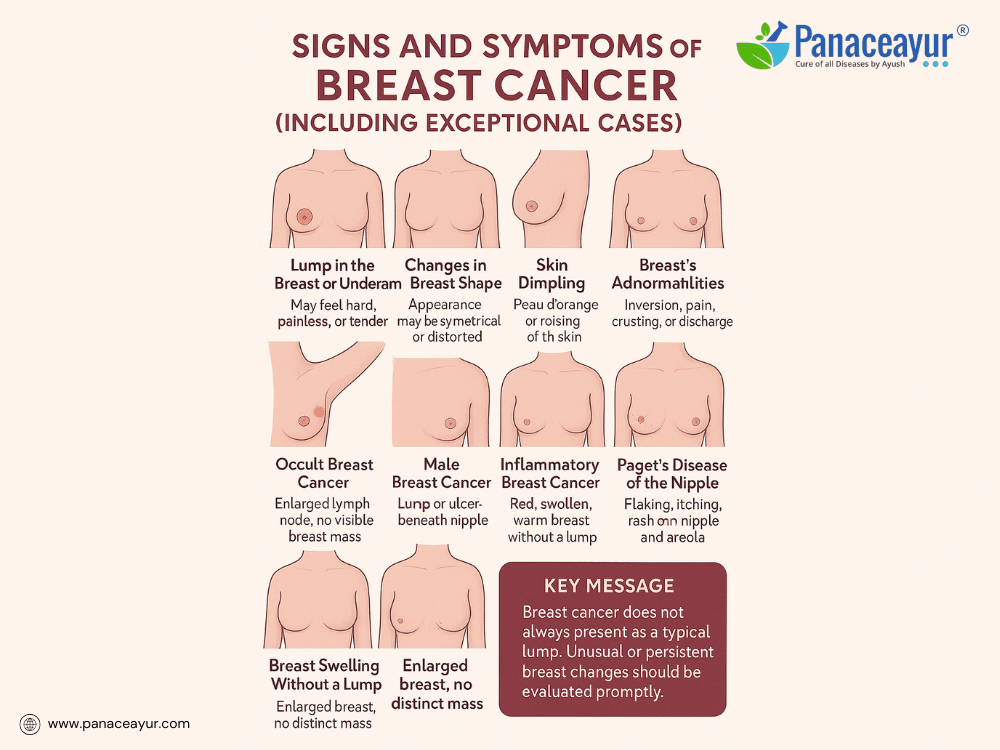

- Signs and Symptoms

- Exceptional and Rare Presentations:

- Key Message:

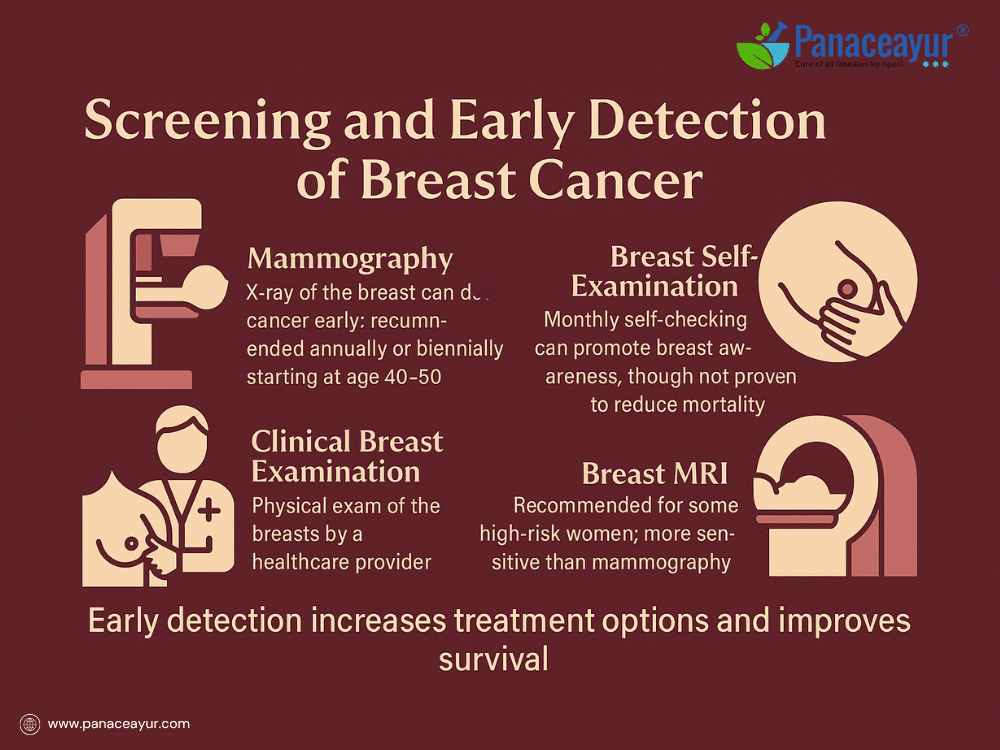

- Screening and Early Detection

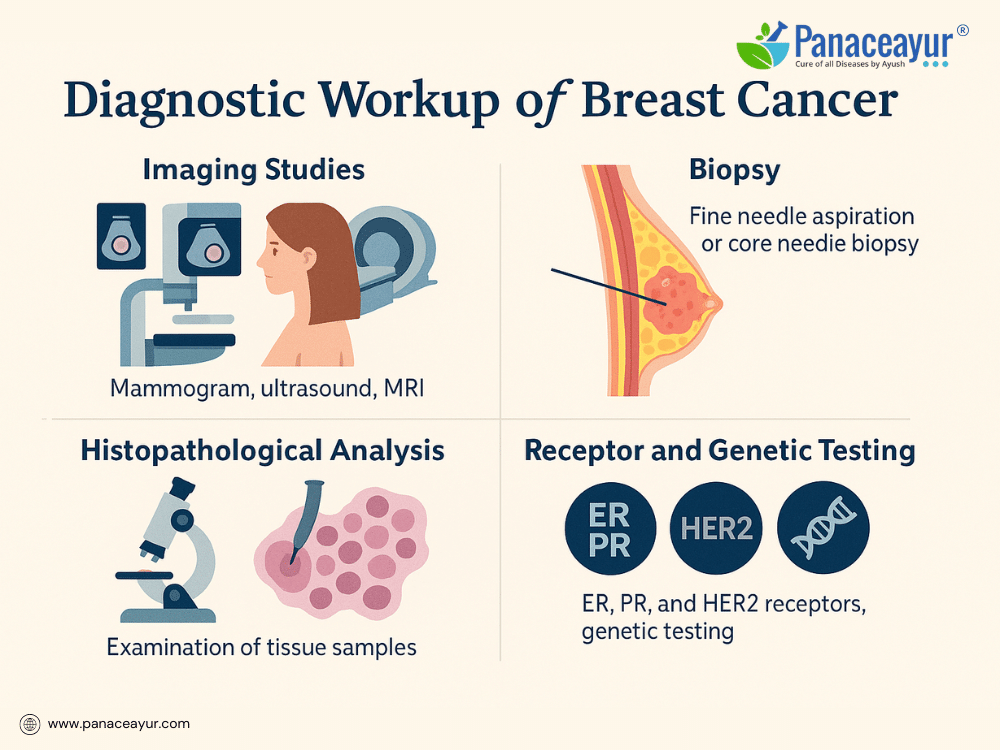

- Diagnostic

- Staging of Breast Cancer

- Treatment Modalities

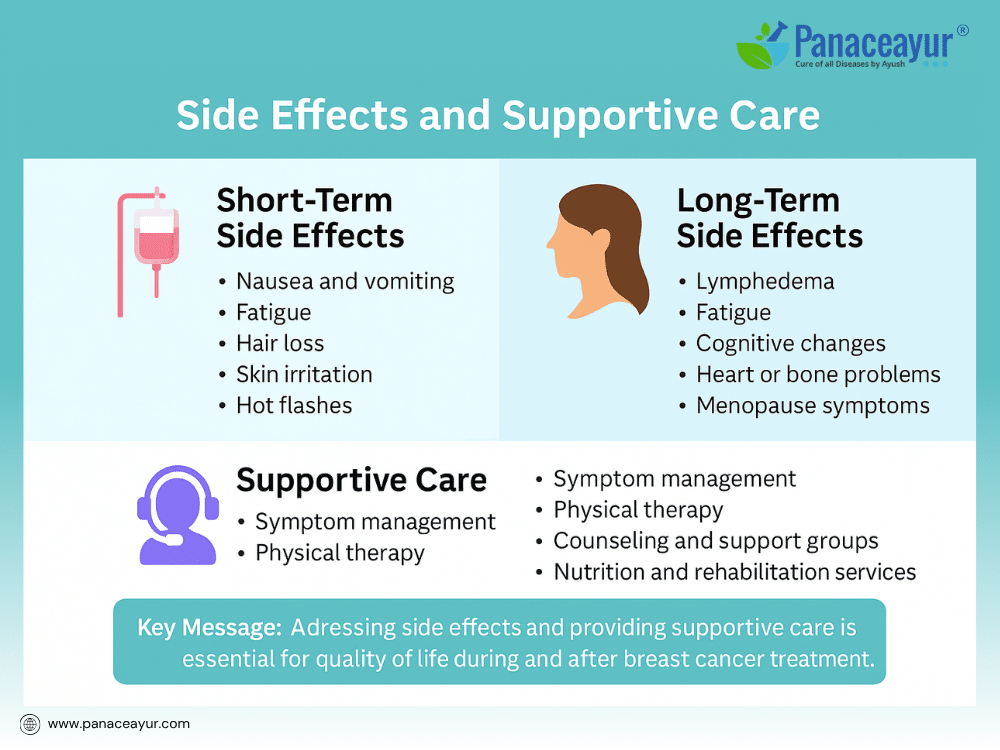

- Side Effects and Supportive Care

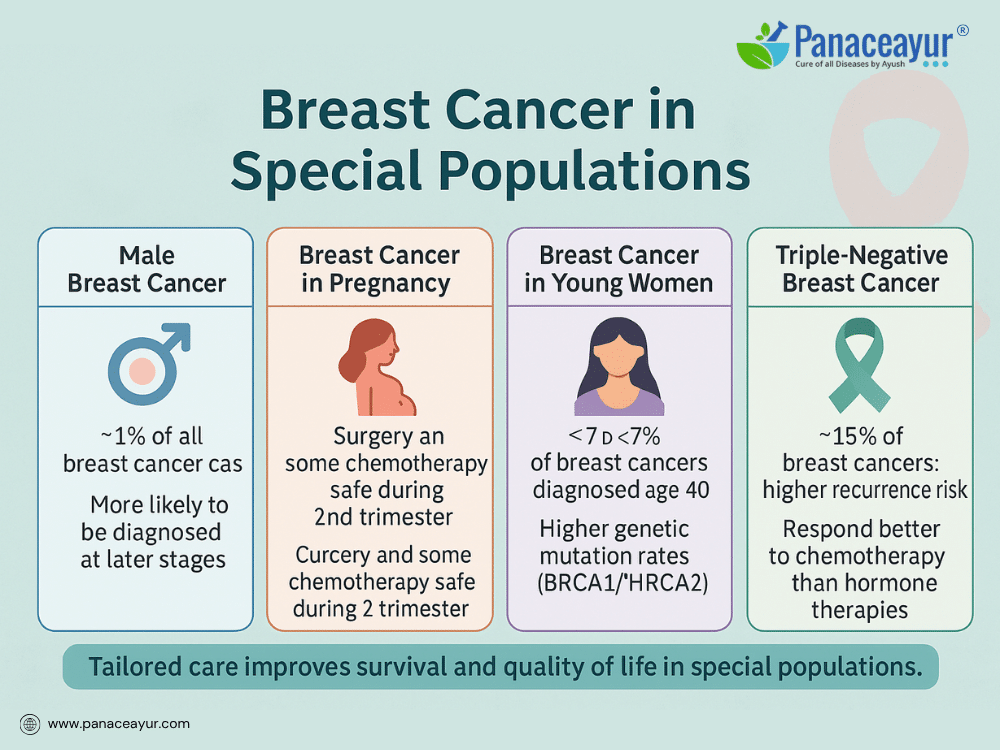

- Breast Cancer in Special Populations

- Prevention Strategies for Breast Cancer

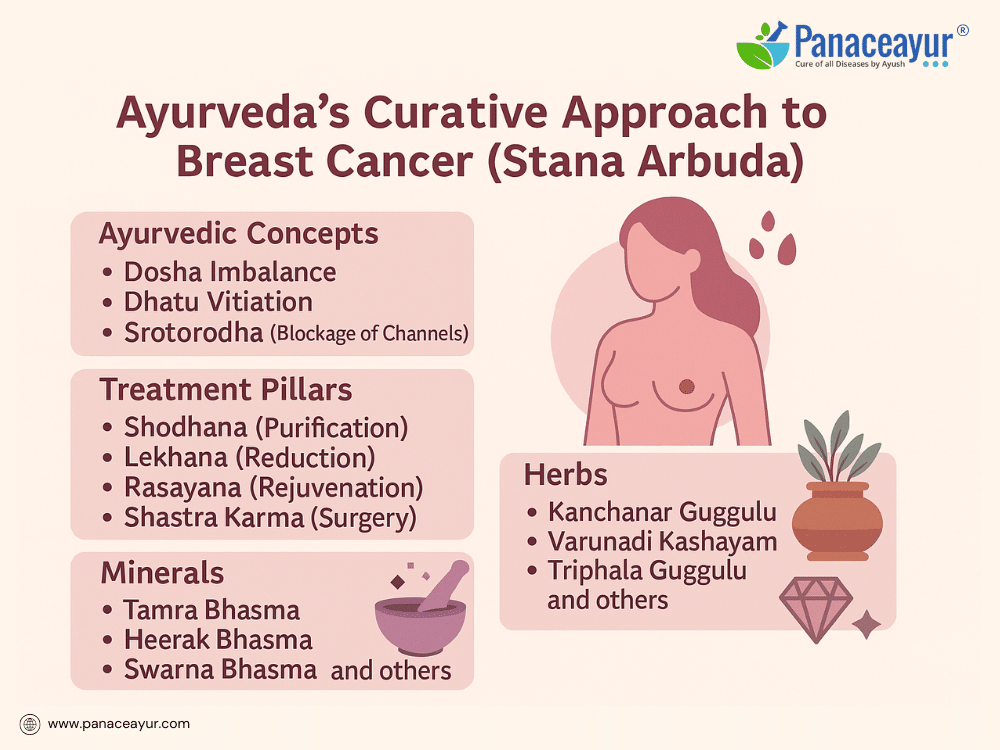

- Ayurveda Cure Breast Cancer

- Case Studies and Clinical Observations

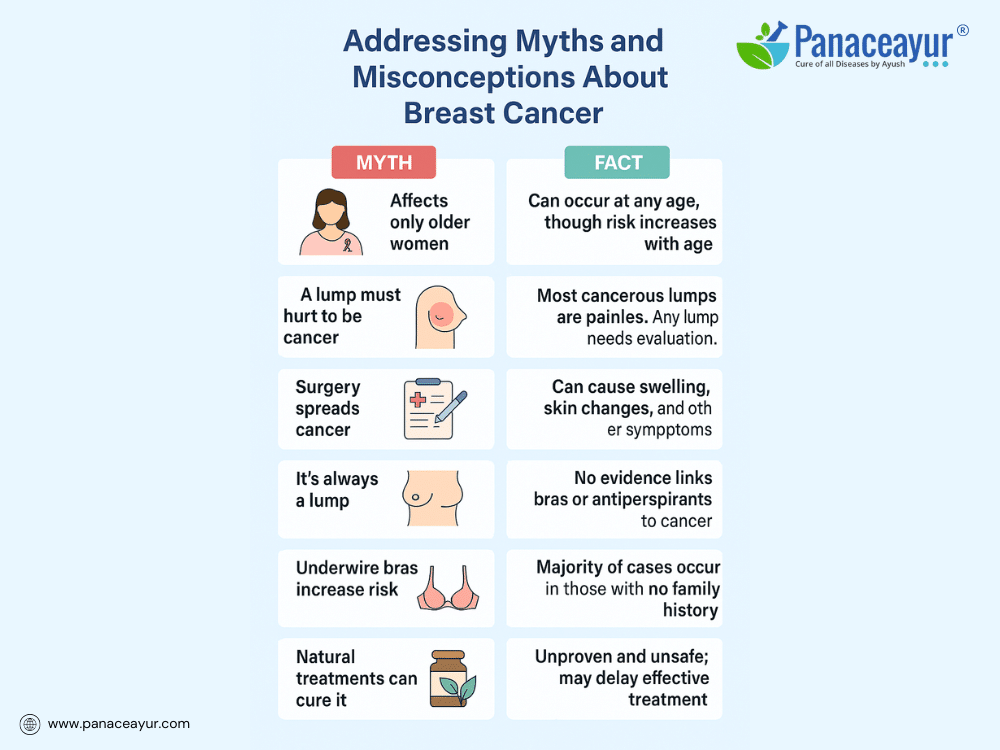

- Addressing Myths and Misconceptions

- References and Further Reading

- Appeal:

Breast cancer is the most common cancer affecting women globally, representing a significant health challenge across both developed and developing countries. Despite advances in detection and treatment, breast cancer continues to impact millions of lives every year, contributing to high morbidity and mortality rates, especially where access to early screening and comprehensive care is limited.

At its core, breast cancer is characterized by the uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells in the breast tissue. These cells may form a lump or mass, invade surrounding tissues, and potentially spread to other parts of the body. The disease encompasses a broad spectrum of presentations, from slow-growing, non-invasive forms to aggressive, life-threatening malignancies. Although predominantly diagnosed in women, breast cancer can also occur in men, albeit rarely.

The historical perspective on breast cancer has evolved over centuries—from ancient times where it was shrouded in mystery and superstition, to today’s sophisticated understanding of its cellular and molecular basis. Modern oncology has shifted towards personalized care, focusing on hormonal influences, genetic mutations, and immune interactions to guide treatment decisions. However, survival outcomes remain strongly influenced by the stage at diagnosis, tumor biology, and the availability of multidisciplinary care.

Parallel to modern advancements, Ayurveda has long recognized conditions resembling breast tumors under the names Stana Arbuda and Stana Granthi. Ayurveda views such diseases not merely as localized growths but as manifestations of deeper imbalances within the body’s energetic systems. It emphasizes correcting the underlying Dosha disturbances, supporting the Dhatus (tissues), and clearing the Srotas (microchannels) to restore physiological harmony.

The convergence of modern oncology and Ayurvedic principles offers an expanded framework for addressing breast cancer—one that not only targets the tumor but also nurtures the whole person. By integrating early detection, effective treatment, and holistic health restoration, this approach holds promise for improving both survival and quality of life.

Types of Breast Cancer

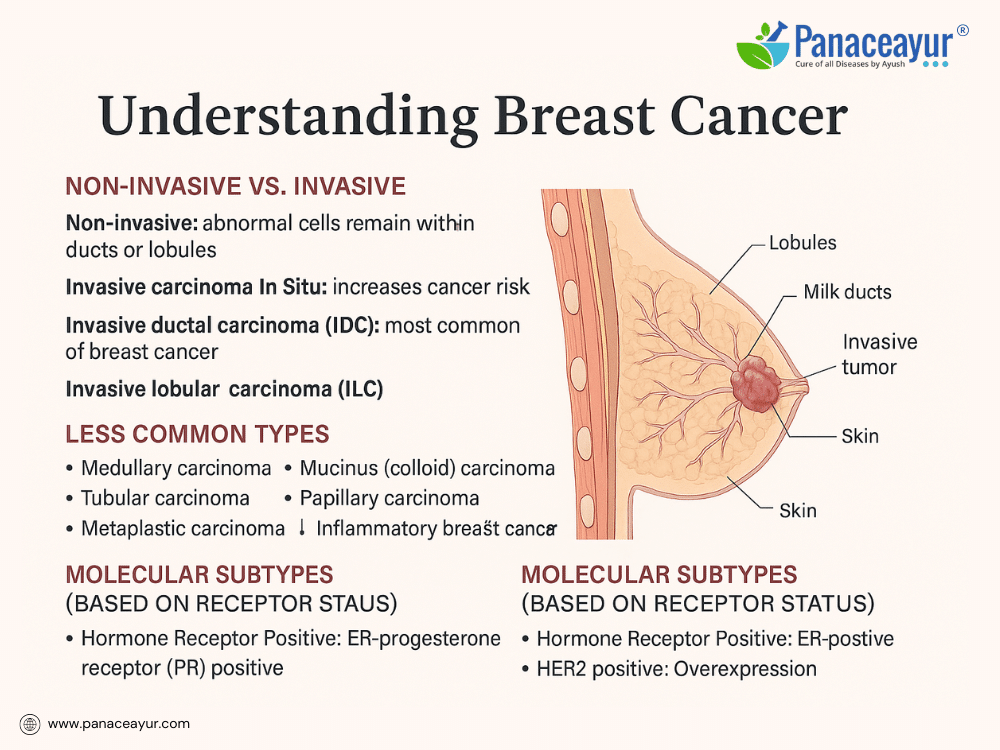

Breast cancer represents a diverse group of diseases rather than a single entity, with variations in behavior, prognosis, and treatment response. Understanding the type of breast cancer is crucial in guiding therapy and predicting outcomes.

Breast cancers are broadly classified as non-invasive (in situ) or invasive (infiltrating). In non-invasive cancers, the malignant cells remain confined within the ducts or lobules without invading surrounding tissue. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is the most common form, characterized by abnormal cells within the milk ducts that have not spread beyond the duct walls. Though non-invasive, DCIS carries the risk of progressing to invasive cancer if left untreated. Another form, lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), involves abnormal cells in the lobules; while not cancer per se, it signals an increased risk of developing invasive cancer in either breast.

In contrast, invasive breast cancers have spread beyond their site of origin into surrounding breast tissue, with the potential to metastasize. The most prevalent type is invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), accounting for approximately 80% of invasive breast cancers. Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) arises from the lobules and can spread diffusely, sometimes presenting as subtle thickening rather than a discrete lump.

Less common types include medullary carcinoma, a rare, well-circumscribed tumor more often associated with BRCA1 mutations; mucinous (colloid) carcinoma, characterized by mucin-producing cancer cells and a generally favorable prognosis; tubular carcinoma, consisting of small, tube-shaped cells with low metastatic potential; and papillary carcinoma, identified by finger-like projections under the microscope. Metaplastic carcinoma represents a heterogeneous group containing mixed cell types, often aggressive and less responsive to standard therapies. Inflammatory breast cancer is rare but highly aggressive, causing breast swelling, redness, and warmth without a distinct mass. Another rare presentation, Paget’s disease of the nipple, manifests as scaly or crusty changes on the nipple and areola, often associated with underlying malignancy.

Modern breast cancer classification also incorporates molecular subtyping based on hormone receptor and growth factor expression. Tumors may be hormone receptor-positive (estrogen and/or progesterone receptor positive), indicating responsiveness to hormone-blocking therapies. HER2-positive cancers overexpress the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, leading to more aggressive growth but also responsiveness to targeted therapies. Triple-negative breast cancers, lacking estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors, tend to be more aggressive and have limited targeted treatment options, requiring reliance on chemotherapy.

Each type represents a distinct biological pathway and therapeutic challenge, underscoring the need for personalized treatment strategies combining surgery, systemic therapy, radiation, and supportive care.

Risk Factors

Breast cancer develops from a combination of risk factors, some of which can be modified through lifestyle changes while others are inherited or unavoidable. Understanding these risk factors empowers individuals to make informed choices and pursue preventive measures where possible.

Among the non-modifiable risk factors, age is one of the most significant; the likelihood of developing breast cancer increases as a woman grows older, with most cases diagnosed after the age of 50. A family history of breast cancer, particularly among first-degree relatives like a mother, sister, or daughter, elevates the risk. Inherited genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2, substantially increase the lifetime risk of both breast and ovarian cancers. Early onset of menstruation (before age 12) and late menopause (after age 55) expose breast tissue to estrogen for a longer duration, contributing to risk. A personal history of breast cancer or certain non-cancerous breast diseases also heightens the chance of future malignancy.

In contrast, modifiable risk factors offer opportunities for prevention. Maintaining a healthy body weight is crucial since excess fat tissue increases estrogen levels, particularly after menopause. Alcohol consumption is directly linked to increased breast cancer risk, even at low to moderate intake levels. Long-term use of hormone replacement therapy, especially combined estrogen and progestin, has been associated with an elevated risk. A sedentary lifestyle, lacking regular physical activity, may further contribute to risk by affecting hormone balance and immune function. Exposure to ionizing radiation, especially during childhood or adolescence, also increases vulnerability.

Environmental and occupational exposures, such as certain pesticides, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and pollutants, are areas of ongoing research. While direct causal links are still being established, minimizing unnecessary exposure is advised.

It’s important to note that having risk factors does not guarantee breast cancer will develop, and many individuals diagnosed with breast cancer have no identifiable risk factors beyond being female and aging. Likewise, some women with multiple risk factors never develop the disease. Awareness of personal risk enables proactive discussions with healthcare providers about screening, genetic counseling, and preventive strategies.

Signs and Symptoms

Recognizing the signs and symptoms of breast cancer is crucial for early detection and better survival. While the majority of patients present with classic features, a subset may exhibit unusual or atypical symptoms, leading to diagnostic delays. Awareness of both typical and exceptional presentations empowers patients and clinicians to pursue timely evaluation.

The most common symptom remains a new lump or mass in the breast or underarm (axilla). These lumps are often hard, irregular, and painless, although some may feel soft or tender. Any persistent breast lump, regardless of pain, firmness, or mobility, warrants further investigation through imaging and biopsy.

Other visible signs include changes in breast shape, contour, or size, particularly asymmetry not previously noted. A subtle flattening, dimpling, or puckering of the skin may indicate an underlying tumor pulling on connective tissue.

A characteristic skin change known as “peau d’orange” (skin resembling the texture of an orange peel) is often a sign of lymphatic obstruction by cancer cells. Similarly, skin thickening, redness, warmth, or scaling may be mistaken for benign conditions like mastitis but could indicate inflammatory breast cancer, an aggressive subtype.

Nipple changes also serve as red flags. These may include nipple inversion (pulling inward), newly developed asymmetry in nipple position, crusting, ulceration, or persistent eczema-like rash (as seen in Paget’s disease of the nipple). Unexplained nipple discharge, particularly if bloody, clear, or from a single duct, requires urgent evaluation.

Axillary swelling or a lump in the underarm area may represent lymph node involvement even before a breast mass becomes palpable.

Breast pain, though not typically a prominent symptom of cancer, can occur in rare instances and should not be dismissed if persistent and localized, especially if associated with other changes.

Exceptional and Rare Presentations:

- Occult Breast Cancer:

In rare cases, breast cancer presents without a detectable breast mass, manifesting solely as enlarged lymph nodes in the armpit or supraclavicular area. Imaging may fail to reveal a primary tumor; diagnosis is made from lymph node biopsy confirming breast origin. - Male Breast Cancer:

Though rare, men can develop breast cancer, typically presenting as a painless lump beneath the nipple, nipple retraction, or skin ulceration. Due to lower suspicion, diagnosis is often delayed. - Inflammatory Breast Cancer:

Presents without a lump, instead causing rapid onset of breast redness, warmth, swelling, and thickened skin. Often misdiagnosed as infection or dermatitis, it requires urgent attention. - Paget’s Disease of the Nipple:

Manifests initially as itching, burning, flaking, or oozing around the nipple-areola complex, mimicking benign skin conditions but linked to underlying breast carcinoma. - Non-palpable Cancer Detected by Screening:

Many breast cancers, especially early-stage ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), are completely asymptomatic, detected solely via routine mammography as microcalcifications. - Distant Metastatic Symptoms as Initial Presentation:

Rarely, a patient may present with symptoms of metastatic disease (bone pain, pathological fractures, neurological deficits, shortness of breath) before any breast mass is identified. - Breast Swelling without Mass:

Some patients experience diffuse swelling or heaviness in one breast, with or without skin changes, due to underlying tumor infiltrating lymphatic drainage. - Bilateral Breast Cancer:

While uncommon, simultaneous or sequential breast cancer in both breasts can occur, often linked to genetic mutations (e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2). Vigilance in screening both breasts is essential. - Breast Cancer in Pregnancy or Lactation:

Presents diagnostic challenges, as breast changes in pregnancy (enlargement, nodularity, tenderness) may mask underlying tumors. Any persistent lump during pregnancy or postpartum warrants imaging. - Painful Breast Masses (Exception):

Although breast cancer masses are typically painless, certain tumors, such as those infiltrating nerve-rich areas or with inflammatory components, can cause discomfort or pain at presentation.

Key Message:

While most breast cancers are detected through noticeable lumps or screening mammograms, atypical and rare presentations exist and must not be overlooked. Any persistent breast or nipple abnormality, skin change, or underarm lump—especially if unexplained—should prompt medical evaluation. Early detection, even in exceptional cases, leads to better outcomes.

Regular screening, self-awareness, and prompt consultation remain vital tools in reducing breast cancer mortality.

Screening and Early Detection

Early detection of breast cancer significantly improves treatment outcomes and survival rates. Screening aims to identify breast cancer at a stage when it is too small to cause symptoms or spread, enabling curative treatment with less aggressive therapies.

The primary screening tool is mammography, a low-dose X-ray of the breast that can detect tumors years before they become palpable. In most Western countries, guidelines recommend regular screening mammograms beginning at age 40 to 50, depending on individual risk factors, and continuing annually or biennially. For women at higher risk, such as those with BRCA gene mutations or a strong family history, screening may begin earlier and include additional modalities.

Clinical breast examination involves a trained healthcare professional physically examining the breasts and underarm areas for lumps, thickening, or skin changes. While less sensitive than imaging, it remains an important adjunct, especially in resource-limited settings or as part of annual physicals.

Breast self-examination (BSE), though widely practiced, is no longer universally recommended as a screening strategy in some guidelines due to lack of evidence showing mortality reduction. However, it plays a valuable role in encouraging breast awareness. Many women still discover their own breast cancers during routine self-checks, underscoring the importance of being familiar with normal breast appearance and feel.

For women at high risk, breast MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is recommended in addition to mammography. MRI is more sensitive for detecting tumors in dense breast tissue or in younger women, though it carries higher false positive rates, potentially leading to more biopsies.

Emerging technologies like 3D mammography (digital breast tomosynthesis) and molecular imaging are improving detection rates, especially in women with dense breasts. Artificial intelligence tools are also being explored to enhance interpretation accuracy.

It is crucial to emphasize that screening does not prevent breast cancer; it increases the likelihood of detecting cancer at an earlier, more treatable stage. Participation in regular screening, guided by personal risk factors, family history, and clinician advice, remains a cornerstone of breast cancer control.

Early detection empowers patients with more treatment choices, lowers the need for extensive surgery or chemotherapy, and improves long-term survival. Promoting awareness of screening guidelines and reducing barriers to access are essential public health goals in reducing breast cancer mortality.

Diagnostic

Once an abnormality is detected—whether through self-examination, clinical examination, or screening mammography—further diagnostic evaluation is essential to confirm the presence of cancer, determine its characteristics, and guide treatment planning.

The diagnostic process typically begins with imaging studies. A diagnostic mammogram provides more detailed X-ray views than a screening mammogram, focusing on the area of concern. If findings remain unclear or further assessment is needed, breast ultrasound is commonly performed. Ultrasound is particularly useful for distinguishing solid masses from fluid-filled cysts and is the preferred imaging modality for evaluating abnormalities in dense breast tissue or for guiding needle biopsies.

For women at high risk or those with inconclusive mammogram or ultrasound results, breast MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) may be recommended. MRI offers high sensitivity, particularly in detecting multifocal or multicentric disease, as well as lesions not visible on other imaging. However, it is more expensive, less specific, and prone to false positives, potentially leading to unnecessary biopsies.

A definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy, in which tissue samples are obtained from the suspicious area and analyzed under a microscope. Several types of biopsy procedures are available:

- Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA): Uses a thin needle to withdraw cells for cytology. It is minimally invasive but may not provide sufficient tissue for detailed analysis.

- Core Needle Biopsy: Uses a larger needle to remove small cylinders of tissue, providing more material for histopathological and receptor testing.

- Stereotactic Biopsy: A core biopsy performed with mammographic guidance to sample non-palpable lesions visible only on imaging.

- Surgical (Excisional or Incisional) Biopsy: Involves removing the entire suspicious area (excisional) or a portion of it (incisional) for diagnosis; generally reserved when needle biopsy is inconclusive.

Once tissue is obtained, it undergoes histopathological analysis to confirm malignancy, determine the tumor type and grade, and assess the tumor’s hormone receptor status. Testing includes:

- Estrogen Receptor (ER) and Progesterone Receptor (PR): To determine if the tumor is hormone-sensitive.

- HER2/neu testing: To assess overexpression of the HER2 protein or gene amplification, influencing the use of targeted therapy.

In some cases, genetic testing for BRCA1, BRCA2, or other mutations may be recommended, especially for women with a strong family history, young age at diagnosis, or triple-negative breast cancer.

Staging investigations may follow, including chest X-ray, bone scan, PET-CT, or liver ultrasound if there are symptoms or findings suggesting metastasis.

Together, the imaging, biopsy results, receptor testing, and staging assessments form the foundation for creating a personalized treatment plan. Accurate diagnostic workup is critical not only for confirming the presence of breast cancer but also for guiding therapy that is most effective for the specific tumor biology.

Staging of Breast Cancer

Staging breast cancer is a critical step in understanding the extent of disease, guiding treatment decisions, and estimating prognosis. The stage describes how large the tumor is, whether cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes, and if it has metastasized to distant organs.

The most widely used system is the TNM staging system, developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). TNM stands for:

- T (Tumor): Describes the size of the primary tumor and whether it has invaded nearby tissues.

- N (Nodes): Indicates whether cancer has spread to regional lymph nodes, and if so, how many nodes are involved.

- M (Metastasis): Identifies whether cancer has spread to distant sites such as bones, liver, lungs, or brain.

Each category receives a numerical value (e.g., T1, N0, M0), which are then combined to assign an overall stage from 0 to IV:

- Stage 0 (Carcinoma in situ): Non-invasive cancer confined within the ducts or lobules; no spread to surrounding tissue.

- Stage I: Small invasive tumor (≤2 cm) with no lymph node involvement.

- Stage II: Tumor between 2–5 cm and/or limited spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- Stage III (Locally advanced): Larger tumor (>5 cm), spread to multiple lymph nodes, or extension to nearby tissues like chest wall or skin.

- Stage IV (Metastatic): Cancer has spread beyond the breast and regional lymph nodes to distant organs.

In addition to anatomic staging, biological factors are now incorporated into modern staging systems, including hormone receptor status (ER, PR), HER2 expression, tumor grade, and proliferation markers like Ki-67. These molecular features influence prognosis and treatment choices, sometimes upgrading or downgrading a stage based on tumor biology.

To accurately stage breast cancer, a combination of imaging and pathology is used. This may include mammograms, breast MRI, ultrasound of lymph nodes, sentinel lymph node biopsy, chest X-ray, bone scan, liver ultrasound, CT scan, or PET-CT depending on clinical suspicion.

Staging plays a pivotal role in determining treatment options. Early-stage cancers (Stage 0–II) are often treated with surgery and radiation, with or without systemic therapy, while Stage III may require neoadjuvant (pre-surgical) chemotherapy to shrink tumors before surgery. Stage IV breast cancer is typically managed with systemic therapies aimed at prolonging life and controlling symptoms rather than cure.

An accurate staging evaluation empowers both patient and clinician to understand the disease’s trajectory and tailor treatment to individual needs.

Treatment Modalities

The treatment of breast cancer is highly individualized, guided by the stage of disease, tumor biology, the patient’s overall health, and personal preferences. Most treatment plans combine local therapies aimed at removing or destroying the tumor in the breast and nearby tissues, along with systemic therapies designed to target potential cancer cells that may have spread elsewhere in the body.

Surgery remains the foundation of breast cancer treatment. The primary surgical approaches include lumpectomy, also known as breast-conserving surgery, and mastectomy. Lumpectomy involves removing the tumor along with a margin of healthy surrounding tissue, while preserving the majority of the breast. This procedure is typically followed by radiation therapy to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence in the remaining breast tissue. In contrast, mastectomy entails removal of the entire breast and may be chosen based on tumor size, multiple tumor locations, patient preference, or genetic factors. Some patients undergoing mastectomy may opt for immediate or delayed breast reconstruction, using either implants or their own tissue to restore breast contour. The evaluation of lymph node involvement is an important component of surgery. A sentinel lymph node biopsy identifies the first lymph nodes likely to contain cancer cells; if these are positive for metastasis, a more extensive axillary lymph node dissection may be performed to remove additional lymph nodes.

Radiation therapy plays a key role in reducing the risk of local recurrence following breast-conserving surgery and, in certain cases, after mastectomy. High-energy beams are directed to the breast, chest wall, or lymph node regions to destroy microscopic cancer cells that may remain. Advances in radiation delivery, such as intraoperative radiation therapy and partial breast irradiation, aim to limit radiation exposure to healthy tissues, thereby reducing side effects.

Systemic therapies are used to treat cancer cells that may have spread beyond the breast and lymph nodes. These treatments may be given before surgery, known as neoadjuvant therapy, to shrink tumors and make them operable, or after surgery, known as adjuvant therapy, to lower the risk of recurrence. Chemotherapy, which uses cytotoxic drugs to kill rapidly dividing cancer cells, is typically recommended for aggressive tumors, hormone receptor-negative cancers, HER2-positive cancers, or when cancer has spread to lymph nodes. Hormonal therapy is a mainstay of treatment for cancers that express estrogen or progesterone receptors. Medications such as tamoxifen, effective in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women, and aromatase inhibitors like anastrozole or letrozole, used in postmenopausal women, work by blocking or lowering estrogen levels to slow cancer growth. Targeted therapy, particularly for HER2-positive breast cancers, includes monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab and pertuzumab that specifically target the HER2 protein, improving outcomes when combined with chemotherapy. Immunotherapy, while still emerging in breast cancer, has shown promise in certain patients with triple-negative breast cancer; agents like atezolizumab, used alongside chemotherapy, are expanding treatment possibilities in this challenging subtype.

Many patients also explore complementary therapies to support their well-being during and after treatment. Integrative approaches, including acupuncture, yoga, meditation, dietary counseling, and evidence-based herbal therapies, may help manage side effects, reduce stress, and enhance quality of life. These supportive measures should be coordinated with the oncology care team to avoid potential interactions or interference with standard treatments.

Breast cancer treatment today is designed and delivered through a multidisciplinary team approach. Surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, plastic surgeons, genetic counselors, and supportive care specialists collaborate to develop a comprehensive plan tailored to each patient’s needs and goals. This coordinated care ensures that treatment not only focuses on controlling or curing the disease but also addresses physical function, cosmetic outcomes, emotional well-being, and long-term survivorship.

Side Effects and Supportive Care

Breast cancer treatment, while effective, can bring a range of side effects that affect the body, mind, and daily life. Addressing these side effects is a crucial part of comprehensive care, ensuring patients not only survive but maintain the best possible quality of life during and after treatment.

Short-term side effects often occur during or immediately after active treatment. Chemotherapy may cause nausea, vomiting, fatigue, hair loss, increased risk of infections, changes in taste, and low blood counts. Radiation therapy may lead to localized skin irritation, redness, peeling, or mild swelling in the treated area. Hormonal therapies can produce symptoms such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, mood swings, or joint stiffness. Targeted therapies and immunotherapies may cause diarrhea, liver enzyme abnormalities, or infusion reactions, depending on the specific agent.

Long-term side effects may emerge months or years after treatment ends. These can include lymphedema, a chronic swelling of the arm or chest wall due to lymph node removal or radiation. Some patients experience persistent fatigue, changes in cognitive function often referred to as “chemo brain,” or premature menopause. Heart and bone health may be affected, especially in patients receiving certain chemotherapy drugs or hormonal treatments. Survivors may also face body image concerns, sexual health challenges, or lingering emotional distress.

Supportive care addresses these physical, psychological, and social effects through an integrated approach. Symptom management strategies include medications for nausea, anemia, neuropathy, or hormonal symptoms. Lymphedema may be treated with physical therapy, compression garments, and specialized massage techniques. Fatigue is addressed through energy conservation, exercise rehabilitation programs, and treating underlying causes like anemia or thyroid dysfunction.

Emotional and mental health support is equally vital. Counseling, support groups, mindfulness practices, and survivorship education help patients cope with the stress and emotional burden of cancer treatment. Addressing concerns about intimacy, fertility, and family planning requires sensitive, proactive discussions between healthcare providers and patients.

Nutritionists, social workers, financial counselors, and rehabilitation specialists form part of the extended supportive care team, helping patients navigate practical challenges during and after treatment. Survivorship care plans, outlining follow-up schedules, lifestyle recommendations, and screening for late effects, empower patients to transition from active treatment into recovery with confidence and support.

By recognizing and proactively managing side effects, supportive care transforms the cancer journey into a more tolerable, holistic experience, ensuring that patients’ well-being is prioritized alongside the goal of disease control.

Breast Cancer in Special Populations

While breast cancer predominantly affects women over 50, it can occur in diverse patient groups, each with unique challenges in diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. Understanding these special populations ensures that care is tailored to their specific needs.

Male Breast Cancer is rare, accounting for about 1% of all breast cancer cases. Men typically present with a painless lump beneath the nipple or areola, often diagnosed at later stages due to lack of awareness and delayed evaluation. Risk factors include BRCA2 mutations, Klinefelter’s syndrome, testicular disorders, and radiation exposure. Treatment parallels that of female breast cancer, including surgery, radiation, and systemic therapies, but psychosocial support addressing masculinity and stigma is especially important.

Breast Cancer in Pregnancy (Gestational Breast Cancer) presents diagnostic and treatment complexities. Physiologic changes during pregnancy—breast enlargement, nodularity, tenderness—can mask tumors, leading to delayed diagnosis. Any persistent breast lump during pregnancy warrants imaging with ultrasound, which is safe in this context. Treatment decisions balance maternal survival and fetal safety. Surgery and certain chemotherapies can be performed during pregnancy, but radiation and hormone therapy are typically postponed until after delivery.

Breast Cancer in Young Women (Under 40 Years) poses additional considerations. Younger patients are more likely to have aggressive tumor subtypes, including triple-negative or HER2-positive cancers, and higher rates of genetic mutations. Fertility preservation is a major concern, as chemotherapy and hormonal therapy can impair reproductive capacity. Discussions about egg or embryo freezing before treatment are crucial. Psychosocial impacts may also be greater, affecting career plans, dating, family-building, and body image at pivotal life stages.

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC), defined by the absence of estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors, is more common in younger women and certain ethnic groups, including African American women. TNBC tends to grow faster, with higher risk of recurrence and limited targeted treatment options. Chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment, with immunotherapy emerging as a promising addition in select patients.

Breast Cancer in Survivors of Other Cancers is an increasingly recognized population, as treatments like chest radiation for lymphoma can increase later breast cancer risk. Screening protocols may begin earlier in these high-risk groups.

Each of these special populations benefits from multidisciplinary, personalized care that integrates medical treatment, genetic counseling, fertility preservation, psychosocial support, and survivorship planning. Tailoring care to these unique circumstances improves both outcomes and the overall patient experience.

Prevention Strategies for Breast Cancer

While not all cases of breast cancer can be prevented, research has identified several modifiable risk factors and strategies that can lower the likelihood of developing the disease. Prevention efforts focus on reducing exposure to known risks, promoting protective behaviors, and identifying high-risk individuals for proactive interventions.

Maintaining a healthy body weight is one of the most significant modifiable factors. Excess body fat, particularly after menopause, increases estrogen levels, which may stimulate the growth of hormone receptor-positive breast cancers. Regular physical activity, including at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week, has been shown to reduce breast cancer risk by improving hormone regulation, immune function, and weight control.

Limiting alcohol consumption is another key prevention strategy. Even small amounts of alcohol increase the risk of breast cancer, and the risk rises with higher intake. Women are advised to limit alcohol to no more than one drink per day or eliminate it altogether.

Avoiding long-term use of combined estrogen-progestin hormone replacement therapy after menopause can reduce risk, as this therapy is associated with an increased likelihood of developing breast cancer. For women who require hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms, discussing alternative options or the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration is recommended.

Breastfeeding has been associated with a modest reduction in breast cancer risk, particularly for hormone receptor-negative tumors. Women who breastfeed for longer durations may derive greater protective benefits.

For women at high risk of breast cancer due to inherited gene mutations (such as BRCA1 or BRCA2) or strong family history, more intensive preventive strategies may be considered. These include enhanced screening with earlier and more frequent mammograms or breast MRI, risk-reducing medications (chemoprevention) such as tamoxifen or raloxifene, and prophylactic surgeries such as mastectomy or oophorectomy.

Environmental exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, certain pesticides, and ionizing radiation remain under investigation. While direct causation is not always established, minimizing unnecessary exposure to harmful agents, especially during critical developmental windows, may offer additional protective effects.

Public health campaigns promoting breast cancer awareness, healthy lifestyle choices, and access to screening play a critical role in population-wide prevention efforts. While individual risk cannot be completely eliminated, empowering women with knowledge and resources to lower modifiable risks contributes to reducing the overall burden of breast cancer.

Ayurveda Cure Breast Cancer

Ayurveda, India’s ancient system of holistic medicine, offers a profound understanding of breast cancer through the lens of Stana Arbuda, a condition described in classical texts such as the Sushruta Samhita and Charaka Samhita. Stana Arbuda is characterized by an abnormal, progressively enlarging mass in the breast, arising from the pathological derangement of Kapha Dosha and Meda Dhatu (fat tissue). Ayurveda attributes tumor formation to the accumulation of Kapha’s heavy, sticky, and stagnant qualities, combined with a weakened digestive fire (Agnimandya) and Srotorodha (blockage of microchannels), leading to tissue overgrowth.

Classical descriptions portray Arbuda as a firm, immobile, deep-seated, non-suppurating, and painless mass that gradually enlarges—a depiction remarkably aligned with modern presentations of breast tumors. Beyond Dosha-Dhatu imbalance, Ayurveda also recognizes factors such as Dushi Visha (latent environmental toxins), Beejabhava Dosha (inherited predisposition), and chronic metabolic vitiation contributing to tumor pathogenesis. The interplay of genetic susceptibility, environmental exposure, and chronic inflammation in modern oncology finds a philosophical parallel in these Ayurvedic explanations.

Ayurveda classifies tumors based on prognosis: Sadhya (curable) tumors are small, superficial, and responsive to purification therapies; Krichra Sadhya (difficult to cure) tumors are deeper and involve multiple tissues; Asadhya (incurable) tumors are advanced, ulcerated, or systemic. This classification guides therapeutic intensity and intervention choices.

The Ayurvedic approach to treating Stana Arbuda is holistic and multi-modal, aiming not only to reduce tumor mass but to correct the internal environment that allowed it to form. Treatment begins with Nidana Parivarjana, the elimination of causative factors such as poor dietary habits, environmental exposure, and stressors that aggravate Kapha and Meda. This is followed by Shodhana Chikitsa (purificatory therapies), including Virechana (purgation) to clear accumulated Pitta-Kapha, Raktamokshana (therapeutic bloodletting) to detoxify Rakta Dhatu, and Basti (medicated enemas) to regulate Vata-Kapha balance and eliminate residual toxins.

Subsequently, Lekhana Chikitsa (scraping therapies) are employed using specific herbal and mineral formulations designed to reduce abnormal tissue growth. Among the most valued formulations are Kanchanar Guggulu, known for its anti-tumor and lymphatic decongestant properties; Varunadi Kashayam, supporting lymphatic clearance and anti-inflammatory action; and Triphala Guggulu, promoting detoxification and mild scraping activity. Additional preparations such as Pushyanuga Churna and Aragwadhadi Kashayam contribute to blood purification and immune support.

Mineral and metallic preparations play a vital role under the discipline of Rasashastra, leveraging their potent bioactivity under precise purification and preparation. Key minerals include Tamra Bhasma (copper ash) for its scraping and anti-Kapha properties; Swarna Makshik Bhasma (chalcopyrite ash) as a metabolic and Rasayana agent; Abhrak Bhasma (mica ash) to rejuvenate tissues and modulate Vata-Pitta; Heerak Bhasma (diamond ash) for rare Rasayana and purported anti-cancer effects; Gandhak Rasayan (purified sulfur) for immunity and detoxification; and Trivanga Bhasma (tin-zinc-lead ash) for hormonal regulation and metabolic support. Additional formulations such as Loha Bhasma, Shankha Bhasma, Godanti Bhasma, and Ras Sindoor are tailored according to patient constitution and tumor characteristics.

Beyond direct tumor reduction, Rasayana Chikitsa (rejuvenative therapy) plays a crucial role in long-term healing and preventing recurrence. Rasayana herbs such as Ashwagandha, Shatavari, Guduchi, Swarna Bhasma, and Mukta Pishti nourish the tissues, enhance immune resilience, restore Ojas (vital energy), and support systemic balance post-detoxification.

Surgical intervention, or Shastra Karma, is reserved for hard, immobile tumors that do not respond to medical management, aligning with Ayurvedic guidance for physical excision when necessary. Post-surgical healing is supported by Ayurvedic wound care using Jatyadi Ghrita, Neem Taila, and Rasayana to accelerate recovery and prevent complications.

Ayurveda’s approach transcends a tumor-centric model, focusing on restoring balance to the entire physiological terrain. By clearing Srotas, rebalancing Doshas, strengthening Agni, purifying Dhatus, and enhancing Ojas, Ayurveda creates an internal environment inhospitable to further pathological growth. This root-cause correction philosophy aims not merely for tumor shrinkage but for holistic, sustainable healing.

Integration of Ayurveda with modern diagnostic tools, imaging, and monitoring allows for a complementary, evidence-informed care plan. While Ayurveda maintains its distinct methodology, it holds promise as an adjunct or alternative pathway to support patients seeking a natural, terrain-centered approach to breast cancer care.

Case Studies and Clinical Observations

Real-world case studies provide valuable insights into the practical application of Ayurvedic therapies for breast cancer (Stana Arbuda) and highlight the potential benefits of integrating traditional and modern medical approaches. These observational accounts underscore not only clinical outcomes but also improvements in quality of life, immune resilience, and emotional well-being.

One illustrative case involved a 42-year-old woman diagnosed with Stage II estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. After undergoing lumpectomy and radiation therapy, she opted for an integrative protocol under Ayurvedic guidance to support recovery and reduce recurrence risk. Her personalized Ayurvedic regimen included Kanchanar Guggulu, Varunadi Kashayam, Tamra Bhasma, Swarna Makshik Bhasma, along with Ashwagandha Rasayan and Guduchi as part of her Rasayana therapy. Over a period of 12 months, she reported sustained energy levels, minimal post-treatment fatigue, improved digestion, and absence of significant lymphedema. Follow-up imaging and tumor markers remained stable at 18 months post-treatment.

Another case highlighted a 55-year-old woman with triple-negative breast cancer who declined chemotherapy after mastectomy due to concerns over side effects. Under close monitoring and informed consent, she pursued an Ayurvedic protocol emphasizing Shodhana (detoxification), Lekhana (scraping therapy), and Rasayana with formulations such as Kanchanar Guggulu, Gandhak Rasayan, Abhrak Bhasma, Heerak Bhasma, and supportive Rasayana herbs. Over 24 months of follow-up, she maintained stable scans with no evident recurrence, while reporting improved mental clarity, emotional stability, and enhanced appetite and strength.

Clinical observations in patients incorporating Ayurveda alongside conventional treatments frequently note better tolerance to chemotherapy and radiation, reduced gastrointestinal and hematological toxicities, fewer infections, and faster post-treatment recovery. Many patients also describe enhanced emotional resilience, reduced anxiety, and a greater sense of empowerment during their healing journey.

However, case studies also highlight the need for individualized care, close monitoring, and transparent communication between all healthcare providers involved. Not every case achieves tumor regression, but quality of life and functional improvements are consistently reported. Integrating Ayurveda as a supportive system rather than an exclusive alternative remains a key principle in ensuring safety and efficacy.

Documented clinical observations continue to support the hypothesis that Ayurvedic interventions may offer valuable adjunctive benefits in breast cancer care, particularly through terrain correction, immune modulation, detoxification, and long-term health restoration. Larger, controlled studies will further elucidate the potential role of Ayurveda in integrative oncology.

Addressing Myths and Misconceptions

Despite widespread awareness campaigns, myths and misconceptions about breast cancer remain pervasive and can hinder early detection, treatment decisions, and emotional well-being. Addressing these misunderstandings with factual, accessible information is crucial for empowering patients and communities.

One common myth is that breast cancer only affects older women. While age is a significant risk factor, breast cancer can and does occur in younger women—and even in men. Awareness of symptoms and screening guidelines across all age groups is essential for timely diagnosis.

Another misconception is the belief that a lump must be painful to be dangerous. In reality, most breast cancer lumps are painless, firm, and irregular. Waiting for pain to develop before seeking evaluation can delay diagnosis. Any persistent lump or unusual breast change should prompt medical attention, regardless of pain.

Many patients fear that biopsies or surgery can “spread” cancer. This is medically unfounded. A biopsy or surgery does not cause cancer to spread; instead, they provide critical information for diagnosis and treatment planning. Avoiding these procedures due to fear may compromise outcomes.

A common misconception is that breast cancer always presents as a lump. While a palpable mass is a frequent sign, breast cancer can also manifest as skin changes, nipple discharge, inversion, swelling, or redness. Some cases are asymptomatic and detected only through screening mammograms.

Some believe that wearing underwire bras, antiperspirants, or breast injury increases cancer risk. Current scientific evidence does not support these claims. Emphasis should instead be placed on established risk factors like genetics, reproductive history, hormone exposure, and lifestyle factors.

Patients sometimes assume that a family history of breast cancer guarantees their own diagnosis or that lack of family history means no risk. In truth, while family history increases risk, the majority of breast cancers occur in women with no family history.

A damaging myth is that “natural treatments alone can cure breast cancer”. While natural and integrative therapies play valuable supportive roles, ignoring evidence-based medical treatment in favor of unproven alternatives can lead to disease progression and poorer outcomes. Combining holistic approaches with standard care under professional guidance offers safer, more effective results.

Finally, some survivors report feeling pressure to “stay positive” or avoid expressing fear or sadness. While optimism supports resilience, emotional honesty is equally important. Creating spaces for patients to express the full range of emotions fosters authentic healing.

Addressing these myths through education empowers individuals to make informed decisions, seek timely care, and navigate breast cancer with clarity and confidence. Dispelling misinformation enhances not only health literacy but also the collective ability to support patients with compassion and evidence-based knowledge.

References and Further Reading

Appeal:

If any reference link does not open due to a technical error or future webpage updates, you are encouraged to search by the researcher’s name, article title, or simply copy and paste the reference into a search engine or scientific database. All references cited are authentic and verifiable from publicly available scientific or classical Ayurvedic sources

- American Cancer Society. (2024). Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2023-2024. Atlanta: American Cancer Society. Available at: https://www.cancer.org

- National Cancer Institute. (2024). Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Patient Version. Retrieved from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/patient/breast-treatment-pdq

- Sushruta Samhita, Nidana Sthana, Chapter 11, Verse 4-5. Chaukhambha Sanskrit Pratishthan Edition.

- Charaka Samhita, Chikitsa Sthana, Chapter 7. Edited by Dr. R.K. Sharma and Bhagwan Dash, Chaukhambha Sanskrit Series.

- Bhavaprakasha Nighantu, Guduchyadi Varga, Kanchanara entry. Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy.

- Singh, R. H. (2010). Integrating Ayurveda with modern medicine: Need for a holistic approach. AYU (An International Quarterly Journal of Research in Ayurveda), 31(2), 130–134. doi:10.4103/0974-8520.72361

- Aggarwal, B. B., & Ichikawa, H. (2005). Molecular targets and anticancer potential of indole-3-carbinol and its derivatives. Cancer Letters, 223(2), 145-152. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.036

- Balachandran, P., & Govindarajan, R. (2005). Cancer—an ayurvedic perspective. Pharmacological Research, 51(1), 19-30. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2004.04.010

- Parmar, V. S., Jain, S. C., Bisht, K. S., Jain, R., Taneja, P., Jha, A., … & Rastogi, R. C. (1997). Phytochemistry of the genus Kanchanar and related compounds. Phytochemistry, 46(5), 891-899.

- Pandey, G., & Mandal, A. (2010). Potential anticancer herbal medicines in Ayurveda. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 1(11), 1-15.

- Mehrotra, S., Singh, S., & Srivastava, A. (2010). Anticancer potential of Ayurvedic herbs: A review. Journal of Herbal Medicine and Toxicology, 4(2), 1-8.

- Khan, N., & Mukhtar, H. (2010). Multitargeted therapy of cancer by green tea polyphenols. Cancer Letters, 269(2), 269-280. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.003

- Sharma, A. K., Kumar, A., & Kumar, R. (2015). Rasayana herbs of Ayurveda: Evidence-based review. International Journal of Ayurveda Research, 6(1), 11-18.

- Venkatakrishnan, K., & Deb, S. (2018). Role of Ayurveda in cancer prevention and treatment: A review. Journal of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, 15(2), 1-12. doi:10.1515/jcim-2017-0002

- Gupta, S. C., Sung, B., Kim, J. H., Prasad, S., Li, S., & Aggarwal, B. B. (2013). Multitargeting by curcumin as a strategy to prevent cancer. Cancer Letters, 269(2), 199-225. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.03.008

- Bishayee, A., & Sethi, G. (2016). Bioactive natural products in cancer prevention and therapy: Progress and promise. Seminars in Cancer Biology, 40-41, 1-3. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2016.06.003

- Pandey, M., Shukla, V. K., & Kumar, M. (2005). Role of surgery in breast cancer from an Ayurvedic perspective. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 4(3), 281-284.

- Satoskar, R. S., & Bhandarkar, S. D. (2005). Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics (Revised 21st ed.). Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. Chapter on plant-based anticancer drugs.

- Kaur, G., Athar, M., & Alam, M. S. (2011). Cancer chemopreventive potential of selected medicinal plants and their phytochemicals: A review. Research Journal of Medicinal Plant, 5(2), 135-152.

- Harde, H., Sharma, S., & Kumar, S. (2014). Formulation and evaluation of polyherbal tablets for cancer therapy: An Ayurvedic approach. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 5(6), 2401-2406.