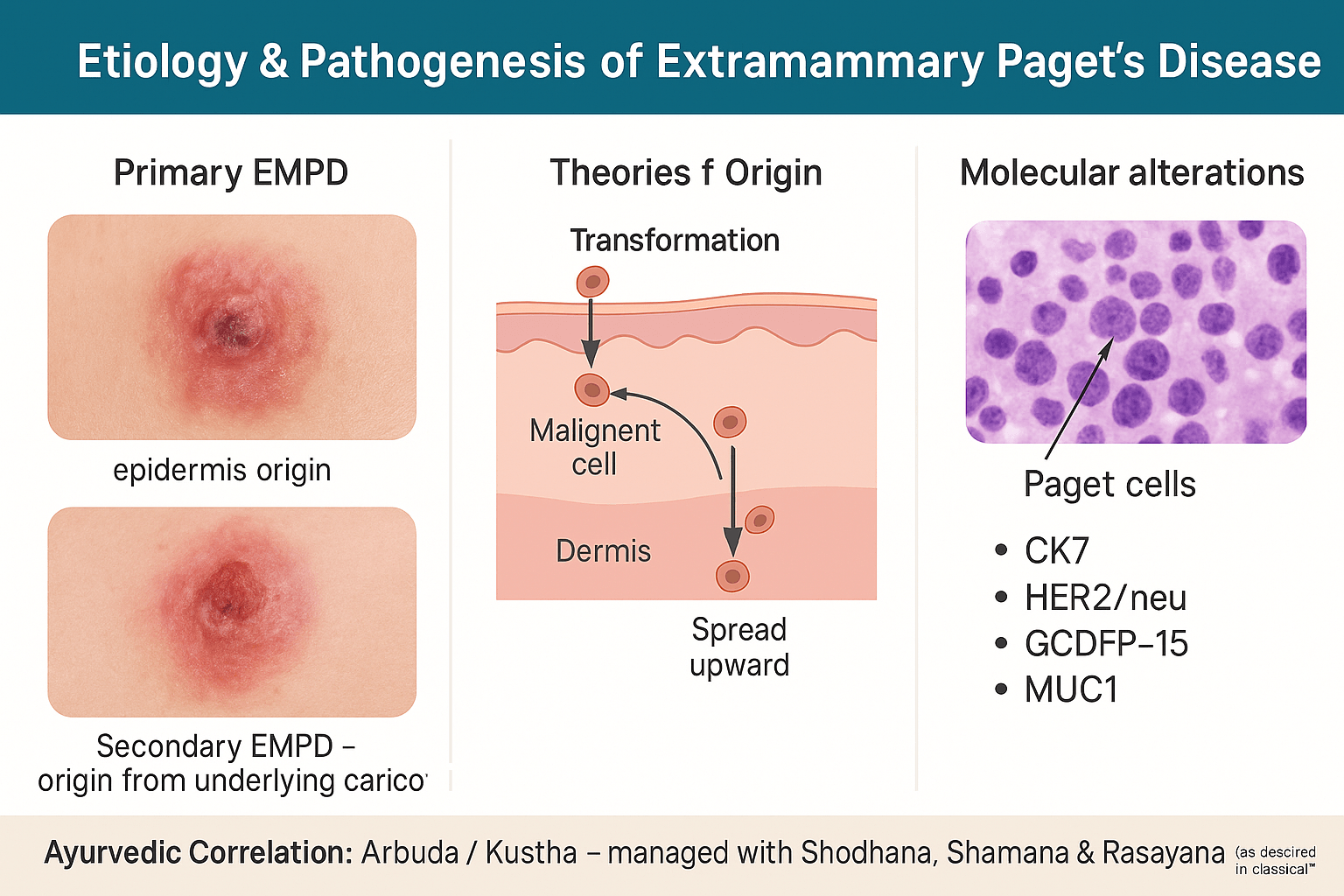

- Etiology and Pathogenesis

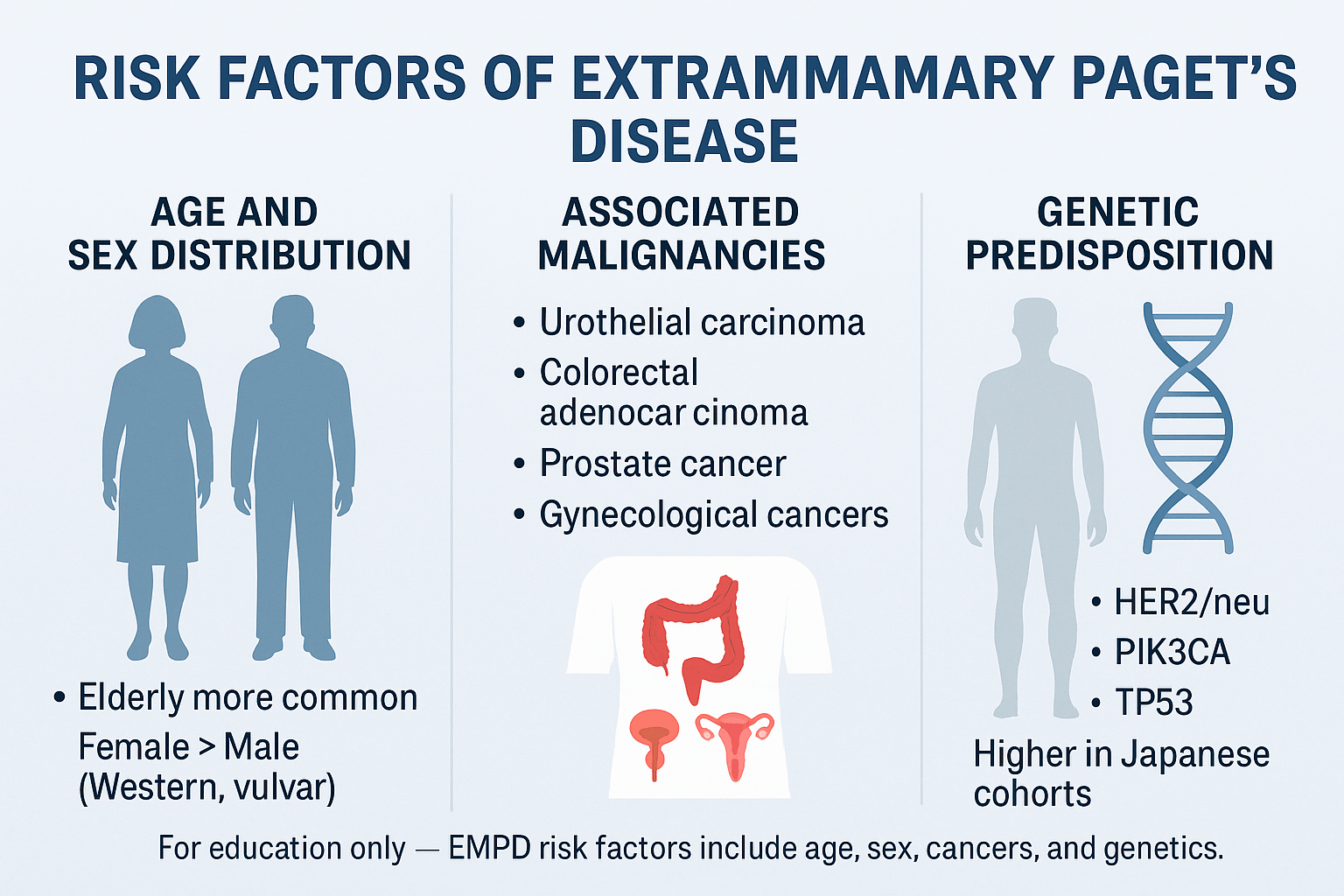

- Risk Factors

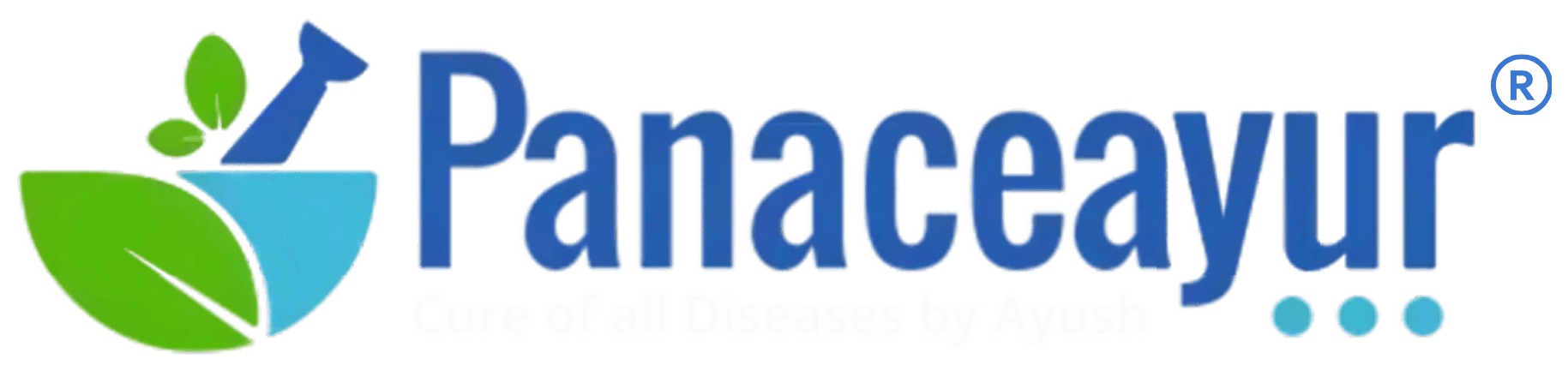

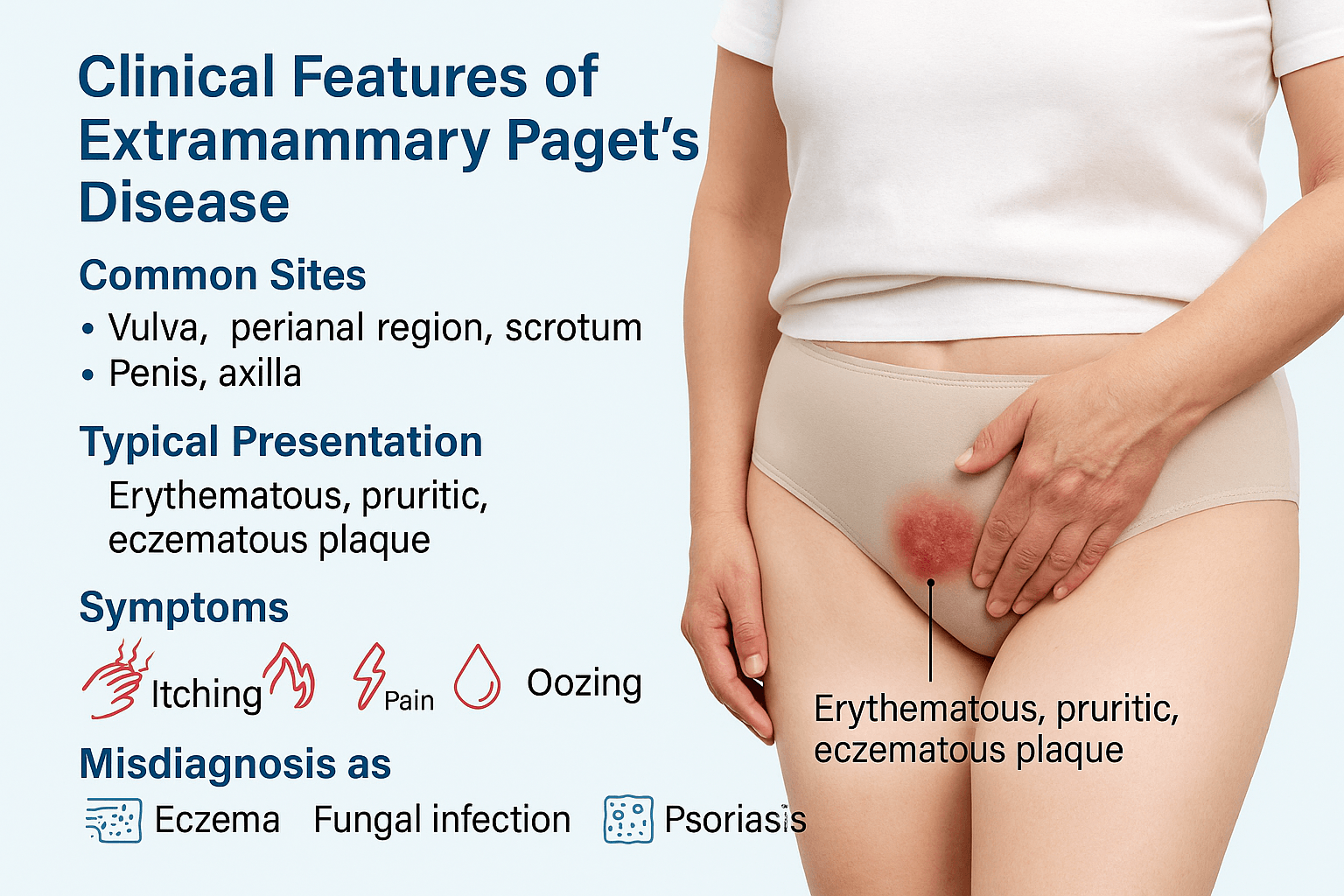

- Clinical Features

- Histopathology of Extramammary Paget’s Disease

- Diagnostic Evaluation of Extramammary Paget’s Disease

- Classification of Extramammary Paget’s Disease

- Treatment Modalities

- Prognosis

- Complications of Extramammary Paget’s Disease

- Differential Diagnosis

- Ayurvedic and Integrative Perspective

- Khadiradi Avaleha for Curing

- ⚠️ Medical Warning

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Extramammary Paget’s Disease (EMPD) is a rare skin cancer that affects areas such as the vulva, scrotum, and perianal region, often misdiagnosed as eczema or fungal infection.In other words it is a rare cutaneous adenocarcinoma that arises in apocrine gland–bearing regions of the body, most frequently the vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and axilla. It is histologically defined by the infiltration of atypical Paget cells, characterized by abundant pale cytoplasm and large hyperchromatic nuclei [1]. Unlike benign dermatoses such as eczema or psoriasis, EMPD is malignant and carries a high risk of local recurrence and potential invasive spread [7]. Because of its chronic eczematous appearance, diagnosis is often delayed, leading to more advanced presentations at the time of detection [13].

Difference Between Mammary and Extramammary Paget’s Disease

Mammary Paget’s Disease (MPD) is almost always associated with underlying ductal carcinoma of the breast, typically manifesting as an eczematous lesion of the nipple–areola complex [4]. By contrast, EMPD occurs in non-mammary sites and may present as either:

- Primary EMPD – arising de novo within the epidermis or apocrine structures, often persisting intraepithelially for years before invasion.

- Secondary EMPD – resulting from epidermotropic spread of a visceral carcinoma, such as those of urothelial, colorectal, or gynecological origin [11].

Although histologically similar to MPD, EMPD is distinct in that nearly one-third of patients present with synchronous or metachronous internal malignancies, necessitating broader systemic evaluation [6].

Epidemiology and Incidence

EMPD accounts for less than 1% of all cutaneous malignancies, making it one of the rarest epithelial tumors of the skin [9]. The incidence varies geographically, with higher prevalence reported in Japan and East Asia compared to Western countries [2]. The disease typically affects elderly individuals, peaking between 60 and 80 years of age, though isolated cases have been documented in younger populations [15].

Gender distribution differs by anatomical site: women are more frequently affected in vulvar EMPD, whereas men are predominantly affected in penoscrotal and perianal EMPD [5]. Epidemiological studies suggest an incidence of approximately 0.1–2 cases per 100,000 population annually [12]. Importantly, invasive EMPD carries a significantly poorer prognosis due to its potential for lymphovascular invasion and nodal metastasis, whereas intraepithelial EMPD tends to follow a more indolent yet recurrent course [8].

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Primary vs Secondary EMPD

The biological behavior of EMPD is shaped by whether it arises as a primary intraepidermal neoplasm or as a secondary manifestation of internal carcinoma.

Primary EMPD originates de novo within the epidermis, most likely from pluripotent keratinocytes or intraepidermal stem cells capable of apocrine differentiation [18]. These lesions often remain confined to the epidermis for long periods, displaying a chronic, indolent clinical course. Yet, over time, some evolve into invasive adenocarcinoma capable of dermal infiltration and regional metastasis [7].

Secondary EMPD, in contrast, represents epidermotropic migration of malignant cells from an underlying visceral carcinoma. The most common associations are with urothelial carcinoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma, and prostate carcinoma [3]. In such cases, Paget cells detected in the epidermis are not primary neoplastic transformations but metastatic or spreading cells from a deeper malignancy. This distinction is vital, as secondary EMPD is more aggressive and mandates extensive systemic screening [22].

Theories of Origin

The pathogenesis of EMPD has been debated for decades, and two complementary models remain central:

- Epidermotropic Spread Hypothesis:

This theory suggests that neoplastic glandular cells from an underlying adenocarcinoma migrate upward into the epidermis through epidermotropic extension. Evidence comes from cases of EMPD linked to colorectal or urothelial carcinomas where the immunophenotype of the skin lesion mirrors that of the visceral malignancy (e.g., CK20 positivity, uroplakin expression) [14]. Clinically, these cases are frequently invasive and carry a poor prognosis. - In-Situ Transformation Hypothesis:

This model proposes that EMPD originates from malignant transformation of epidermal keratinocytes or adnexal apocrine gland cells. Such lesions are often CK7 positive, CK20 negative, and may persist intraepidermally for years without an associated carcinoma [27]. The existence of long-standing, non-invasive EMPD cases with no internal malignancy strongly supports this mechanism [19].

In reality, both mechanisms are likely at play, with primary EMPD following in-situ transformation and secondary EMPD explained by epidermotropic migration. Recent molecular profiling reinforces the concept that EMPD is not a single disease entity but a clinicopathological spectrum [6].

Molecular and Genetic Alterations

Modern immunohistochemistry and molecular diagnostics have provided invaluable insights into EMPD’s biology and origins:

- Cytokeratin 7 (CK7): Nearly all primary EMPD lesions show CK7 positivity, making this a highly sensitive marker for diagnosis. CK7 expression reflects apocrine differentiation of the malignant cells [10].

- Cytokeratin 20 (CK20): CK20 positivity is strongly associated with secondary EMPD, especially in cases linked to colorectal or urothelial carcinomas. A CK7+/CK20+ profile often suggests secondary EMPD, whereas CK7+/CK20− favors primary disease [28].

- HER2/neu amplification: Overexpression of HER2/neu is observed in up to 40–60% of EMPD cases. This has direct therapeutic implications, as anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies (e.g., trastuzumab) have shown promising responses in advanced or metastatic EMPD [16].

- GCDFP-15 (Gross Cystic Disease Fluid Protein-15): GCDFP-15 positivity suggests apocrine differentiation and supports a primary cutaneous origin [21].

- Mucin core proteins (MUC1, MUC5AC): Aberrant mucin expression has been documented in EMPD, aligning its pathogenesis with glandular adenocarcinomas and offering additional diagnostic clues [24].

- Androgen receptor (AR) and Estrogen receptor (ER): Some EMPD lesions express AR and ER, suggesting a potential role for hormonal signaling pathways in tumor progression and possibly expanding therapeutic strategies [31].

Pathobiological Insights

Collectively, these findings emphasize that EMPD is not a uniform disease but a biologically heterogeneous entity. Primary EMPD appears to be a localized cutaneous adenocarcinoma with apocrine differentiation, whereas secondary EMPD represents epidermal colonization by visceral carcinomas. Molecular biomarkers not only aid in differential diagnosis but also highlight new therapeutic targets, shifting EMPD management from a purely surgical disease to one with potential for targeted and personalized therapy [25].

Risk Factors

Age and Sex Distribution

Age remains the most consistent risk factor for EMPD. The disease occurs most often in individuals over 60 years of age, with incidence peaking in the seventh and eighth decades of life [41]. The elderly skin environment, with reduced immune surveillance and altered epidermal repair mechanisms, may predispose to malignant transformation. Although rare, EMPD has been reported in patients under 50, typically linked with aggressive disease or associated malignancy [9].

Sex distribution differs by geography. In Western cohorts, women predominate, with vulvar EMPD representing the majority of cases [33]. In contrast, East Asian populations, particularly in Japan, report a male predominance, largely due to higher incidence of penoscrotal EMPD [12]. These demographic variations point to both environmental and genetic influences on disease patterns [27].

Associated Malignancies

Perhaps the most clinically important risk factor is the association of EMPD with visceral carcinomas. Between 20–40% of EMPD cases are linked with an internal malignancy either at the time of diagnosis or later in the disease course [6].

- Urothelial carcinoma is frequently seen with perineal and penoscrotal EMPD, suggesting direct anatomical and biological connections [18].

- Colorectal adenocarcinoma is strongly associated with perianal EMPD, supporting the epidermotropic spread theory [24].

- Prostate carcinoma has also been detected in men with genital EMPD, sometimes as an incidental finding during staging work-up [32].

- In women, vulvar EMPD may coexist with gynecological malignancies such as cervical, ovarian, or endometrial cancers [15].

The presence of an underlying malignancy dramatically alters prognosis, often converting EMPD from a locally recurrent but indolent disease to one with invasive and metastatic potential. For this reason, a thorough oncologic evaluation — including cystoscopy, colonoscopy, gynecological examination, and imaging — is considered mandatory in the diagnostic pathway [21].

Genetic Predisposition

Most EMPD cases are sporadic, but molecular studies reveal an increasing role of genetic susceptibility. Mutations in HER2/neu, PIK3CA, and TP53 genes have been reported in subsets of EMPD, suggesting overlap with the molecular biology of glandular adenocarcinomas [36]. These mutations may not only drive oncogenesis but also offer therapeutic targets, as seen with HER2-directed therapies in metastatic EMPD.

Rare reports of familial clustering indicate a possible heritable component, though such cases remain exceptional [11]. Furthermore, epidemiological studies highlight ethnic predisposition, with markedly higher rates documented in Japanese cohorts compared to Western populations [25]. This disparity has led researchers to investigate potential polymorphisms related to apocrine gland biology, mucin expression, and immune system regulation as contributors to risk [29].

Clinical Features

Common Sites

Extramammary Paget’s Disease primarily affects areas rich in apocrine glands, with the vulva being the most common site in women [52]. In men, the penoscrotal region is most frequently involved, while the perianal area remains another significant location in both sexes [47]. Less common sites include the axilla and even rare locations such as the thighs or external auditory canal [63]. This anatomical distribution reflects EMPD’s origin from apocrine-bearing skin and adnexal structures.

Typical Presentation

Clinically, EMPD usually appears as a well-demarcated, erythematous, eczematous plaque with irregular borders [38]. The lesion surface may be scaly, crusted, or moist, sometimes with weeping erosions that mimic chronic dermatitis [69]. Over time, the lesion can expand centrifugally and occupy large cutaneous surfaces, creating diagnostic confusion.

Symptoms

Patients commonly report itching (pruritus) as the earliest and most persistent symptom [54]. As the disease progresses, additional complaints include burning sensations, localized pain, oozing, bleeding, and ulceration [61]. Chronic irritation can result in secondary infection, adding to morbidity and further masking the malignant nature of the lesion [72]. Importantly, EMPD may remain asymptomatic in some patients, discovered only during biopsy of a long-standing “eczema-like” lesion [45].

Misdiagnosis

A hallmark challenge in EMPD is its frequent misdiagnosis. Up to half of patients are initially treated for benign dermatologic disorders such as eczema, fungal infections, or psoriasis before histologic confirmation [59]. This delay in recognition contributes to prolonged morbidity and can allow intraepithelial disease to progress into invasive carcinoma. The subtle, nonspecific appearance underlines the need for early biopsy in any chronic, therapy-resistant genital or perianal lesion [66].

Histopathology of Extramammary Paget’s Disease

What doctors look for under the microscope

When a biopsy is done, doctors look for something called Paget cells. These are larger-than-normal cells with pale cytoplasm and big nuclei that often stand out. They can appear scattered in the skin or grouped in clusters. Sometimes they extend down into hair follicles and sweat glands, which is why the disease may spread farther than it looks on the surface.

How staining helps confirm the diagnosis

To make sure the diagnosis is correct, pathologists use special stains and markers. These highlight the unique features of Paget cells and help separate EMPD from other skin conditions.

- PAS stain shows mucin inside Paget cells.

- Mucicarmine also highlights the mucin.

- CK7 is almost always positive in EMPD.

- CK20 may be positive if the disease comes from another cancer, like colorectal or bladder cancer.

- GCDFP-15 supports apocrine gland involvement.

- CEA is often positive and points to gland-like features.

In short, most primary EMPD cases show PAS+, mucicarmine+, and CK7+. If CK20 is positive too, it usually means the disease is secondary and linked to another internal cancer.

Other conditions that look similar

Several skin diseases can mimic EMPD, which is why staining is so important.

- Bowen’s disease (a type of squamous cell carcinoma in situ) looks similar but does not contain mucin.

- Melanoma in situ can also resemble EMPD because the cells spread in a similar way, but melanoma stains positive for S100 and Melan-A instead.

- Mycosis fungoides, a form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, can appear as chronic patches but shows lymphocyte markers instead of mucin or keratin.

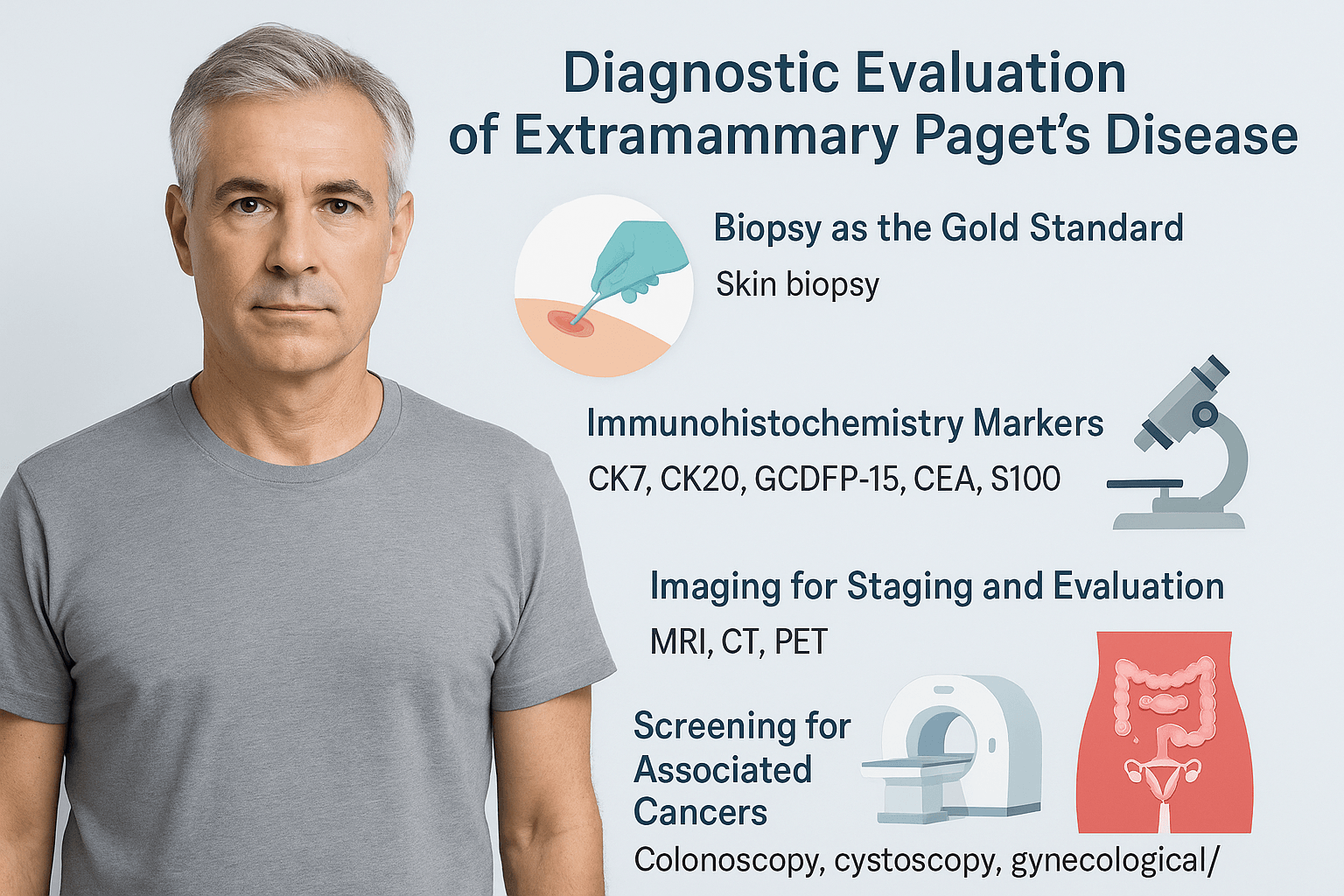

Diagnostic Evaluation of Extramammary Paget’s Disease

Biopsy as the gold standard

The primary method for confirming EMPD is a skin biopsy. A small tissue sample is taken from the lesion and examined under a microscope. The presence of Paget cells confirms the diagnosis. Since EMPD often resembles eczema, psoriasis, or fungal infections, a biopsy is essential to prevent delays in treatment and avoid misdiagnosis [104].

Role of immunohistochemistry

After biopsy, immunohistochemical staining is performed to establish the exact nature of the disease. CK7 is typically positive in primary EMPD, while CK20 may indicate secondary EMPD associated with colorectal or bladder cancer [113]. GCDFP-15 and CEA help confirm the glandular characteristics of the lesion. S100 is used to rule out melanoma, which can mimic EMPD in its early stages [109]. This panel of markers allows doctors to separate EMPD from other skin conditions and identify whether the disease is primary or secondary [118].

Imaging for staging and evaluation

Imaging studies are recommended when invasive or advanced disease is suspected. MRI provides clear views of soft tissue spread, CT scans assess the abdomen and pelvis, and PET scans are sometimes used to detect distant metastasis [97]. These imaging methods are not always required in superficial disease but are important for staging in invasive cases [122].

Screening for associated cancers

Because EMPD is often linked with internal cancers, patients undergo further evaluations. Colonoscopy helps detect colorectal malignancies, cystoscopy assesses the bladder and urinary tract, and gynecological or urological evaluations are performed depending on the lesion site [111]. Detecting an associated cancer is critical, as it changes both prognosis and treatment planning [116].

Classification of Extramammary Paget’s Disease

Primary EMPD

Primary EMPD develops directly in the skin, usually from cells in the epidermis or apocrine glands. It is most often confined to the surface layers of the skin and can persist for years before showing invasive features. This form is considered an intraepidermal adenocarcinoma and has no immediate connection to cancers of internal organs [135].

Secondary EMPD

Secondary EMPD occurs when cancer cells from another organ, such as the bladder, prostate, or colon, extend into the skin. In these cases, Paget cells found in the epidermis are actually the result of spread from a deeper visceral malignancy. Secondary EMPD is more aggressive, has a higher risk of recurrence, and requires thorough screening to find the associated carcinoma [142].

Invasive and non-invasive forms

Both primary and secondary EMPD can be further divided into invasive and non-invasive types. Non-invasive EMPD remains restricted to the epidermis and may follow a chronic but relatively indolent course. Invasive EMPD penetrates into the dermis, with the potential to spread to lymph nodes and distant sites. Invasive disease is associated with worse outcomes and often requires more extensive treatment strategies [129].

Treatment Modalities

Surgical management

Surgery remains the first-line treatment for most cases of EMPD. Wide local excision is commonly performed, with the aim of removing the tumor along with a margin of healthy tissue to reduce recurrence risk [151]. Mohs micrographic surgery is an alternative approach where tissue is removed layer by layer and examined under a microscope in real time. This technique has the advantage of sparing as much normal skin as possible while ensuring complete tumor removal, which is particularly important in sensitive areas such as the vulva, perianal region, and scrotum [147].

Radiotherapy

For patients who are not good candidates for surgery due to age, health status, or anatomical limitations, radiotherapy can be used as a primary treatment. It can also serve as an adjunct after surgery in cases where the tumor has invaded deeply or margins are positive. Radiation provides local control but may not fully prevent recurrence in all cases [159].

Topical therapies

Certain topical medications have shown promise in non-invasive EMPD. Imiquimod cream stimulates the immune system to attack tumor cells, and has been reported to reduce or clear superficial lesions in some patients [153]. Another option is topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which interferes with abnormal cell growth. These treatments are generally reserved for patients with limited disease or those unable to undergo surgery [162].

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy uses a photosensitizing agent applied to the skin followed by exposure to a specific wavelength of light. This combination produces reactive oxygen species that destroy cancer cells. It has been used as a minimally invasive option in selected patients, especially for recurrent or superficial lesions [166].

Laser ablation

CO₂ and erbium:YAG lasers have been applied to EMPD lesions as another non-surgical alternative. Laser therapy vaporizes the abnormal epidermal tissue but does not provide a tissue sample for pathology, which makes it less reliable for confirming complete clearance [149]. It is sometimes considered for palliation or small, superficial disease.

Systemic therapy for advanced or metastatic disease

When EMPD progresses to invasive or metastatic stages, systemic therapy becomes necessary. Conventional chemotherapy regimens, such as taxanes or platinum-based drugs, have been used with variable success [157]. Targeted therapies are emerging, especially for patients whose tumors show HER2/neu amplification. Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody against HER2, has shown encouraging results in advanced EMPD and may become a cornerstone of systemic treatment in the future [164].

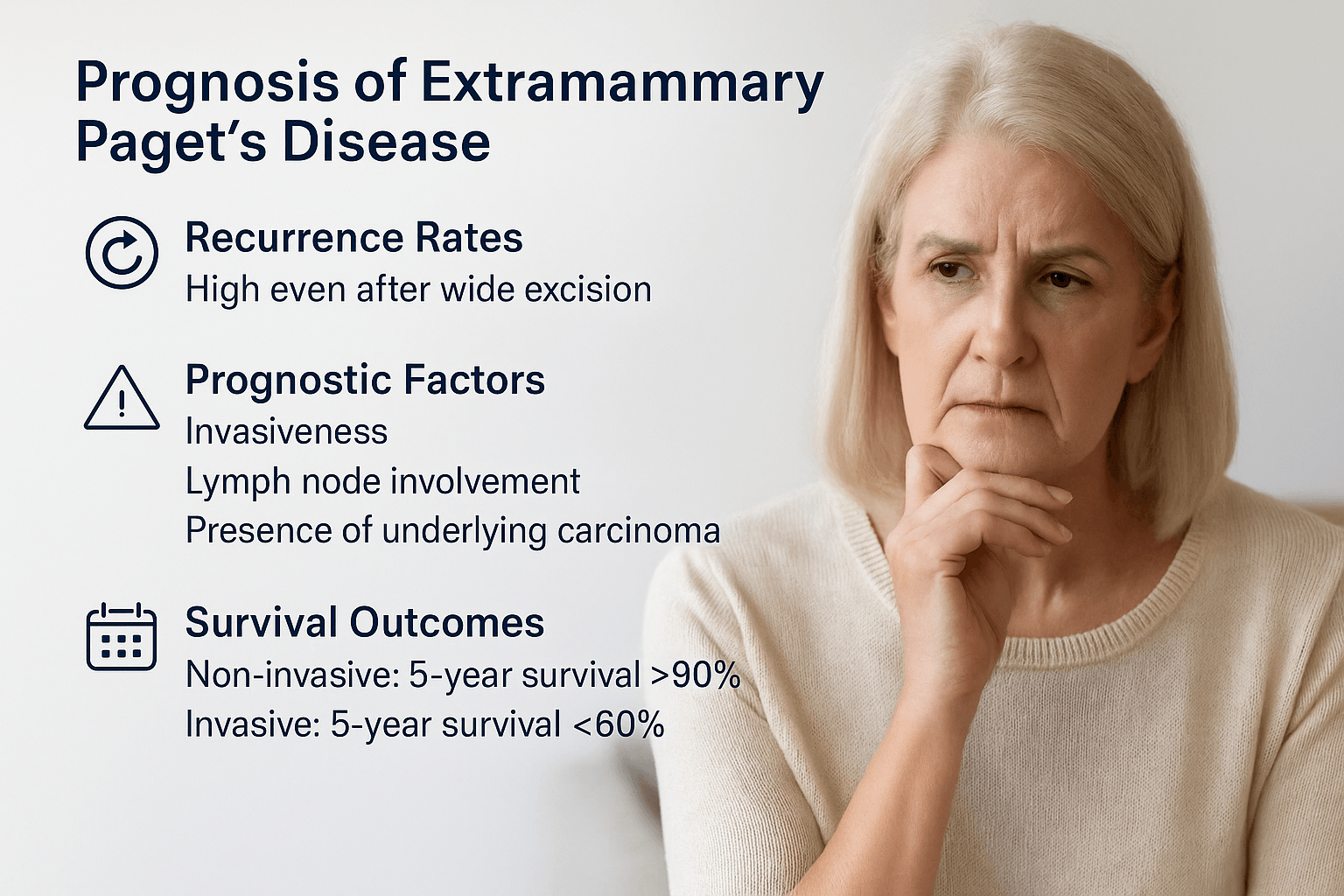

Prognosis

Recurrence rates

One of the most challenging aspects of EMPD is its tendency to recur. Even after wide local excision with apparently clear margins, recurrence rates remain high. Studies have shown recurrence in up to 30–60 percent of patients, reflecting the difficulty of removing microscopic “skip lesions” that extend beyond visible disease [172]. Mohs micrographic surgery reduces but does not eliminate this risk. Long-term follow-up is therefore essential [178].

Prognostic factors

The prognosis depends on several clinical and pathological features. Non-invasive EMPD confined to the epidermis generally has an indolent course but requires careful monitoring [185]. Invasive EMPD, where tumor cells penetrate the dermis, carries a much worse outlook due to the risk of lymphatic and hematogenous spread [192]. Lymph node involvement is a particularly poor prognostic marker and is strongly associated with systemic progression [181]. Another major factor is the presence of an underlying visceral carcinoma, which significantly worsens survival outcomes [189].

Survival outcomes

Patients with intraepidermal EMPD alone can live many years with proper surveillance and local management, but their quality of life may be affected by recurrent lesions and repeated surgeries [175]. Once the disease becomes invasive or associated with internal carcinoma, overall survival declines sharply. Five-year survival rates for non-invasive EMPD can exceed 90 percent, while invasive or metastatic disease reduces survival to less than 60 percent in most series [183].

Complications of Extramammary Paget’s Disease

Recurrence and persistence

One of the most frequent complications of EMPD is recurrence. Even after wide excision, microscopic tumor extensions called “skip lesions” can remain in the skin and cause the disease to return. Reported recurrence rates range from 30 to 60 percent, often requiring repeated surgeries or long-term monitoring [204]. In some cases, lesions may persist chronically without complete resolution despite multiple treatments [211].

Spread to regional lymph nodes

When EMPD progresses from a superficial intraepidermal form to an invasive cancer, it can spread to regional lymph nodes. Lymph node metastasis is a serious complication, as it significantly increases the risk of systemic spread and worsens prognosis. Patients with nodal involvement generally have lower survival outcomes compared to those with disease confined to the skin [218].

Association with other malignancies

Another important complication is the association with synchronous or metachronous cancers. Between 20 and 40 percent of EMPD cases are linked to internal malignancies such as urothelial carcinoma, colorectal adenocarcinoma, prostate cancer, or gynecological cancers [209]. The presence of these associated tumors changes the treatment plan and negatively impacts long-term survival [222].

Treatment-related complications

Both surgical and non-surgical treatments for EMPD carry potential complications. Wide excision or Mohs surgery can cause scarring, disfigurement, and functional impairment in sensitive areas such as the vulva or perianal region [213]. Radiotherapy may result in radiation dermatitis, chronic skin changes, or delayed wound healing [219]. Topical and laser therapies may cause irritation, burning, or incomplete clearance, necessitating further interventions [225].

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic dermatitis or eczema

Chronic dermatitis, particularly in the genital or perianal regions, is often mistaken for EMPD. Both conditions present with red, scaly, and itchy plaques that may become thickened and inflamed over time. In eczema, lesions usually improve with emollients, topical corticosteroids, or antifungal creams. EMPD, however, persists despite these treatments and gradually enlarges in size. A skin biopsy reveals the difference: eczema shows spongiosis and inflammatory infiltrates, whereas EMPD reveals Paget cells within the epidermis [231].

Psoriasis

Psoriasis can mimic EMPD when it affects the genital area, producing red plaques with silvery scales. Unlike EMPD, psoriasis tends to be symmetrical and also appears on typical sites such as the elbows, knees, and scalp. Patients with psoriasis often have a history of flares and remissions, and nail changes (pitting or ridging) may be present. Histologically, psoriasis is characterized by acanthosis, parakeratosis, and elongated rete ridges, while EMPD is defined by mucin-positive Paget cells with CK7 expression [239].

Bowen’s disease

Bowen’s disease, or squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is another close mimic of EMPD. Clinically, it manifests as a slowly enlarging, red, crusted plaque that may ulcerate. On visual inspection alone, it can be difficult to differentiate from EMPD. Histopathology is crucial: Bowen’s disease shows full-thickness atypia of keratinocytes with disorganized maturation, but it lacks mucin production. Immunohistochemical staining also separates the two, as EMPD is CK7 positive, while Bowen’s disease typically is not [228].

Melanoma in situ

Melanoma in situ involving the genital or perianal region may appear similar to EMPD because both present with erythematous or pigmented plaques. A key overlap is the “pagetoid spread” of abnormal cells through the epidermis. However, melanomas often show darker pigmentation or irregular color patterns, which EMPD usually does not. Immunostaining helps distinguish the two: melanoma cells express melanocytic markers such as S100, HMB-45, and Melan-A, while EMPD cells stain for CK7, CEA, and mucin [246]. The consequences of misdiagnosis are serious, as melanoma carries a different prognosis and treatment pathway.

Fungal infections

Chronic fungal infections, especially candidiasis and dermatophytosis, can resemble EMPD when they involve moist intertriginous regions such as the groin or perianal skin. Symptoms include redness, itching, scaling, and sometimes oozing — all of which overlap with EMPD. However, fungal infections often respond to antifungal therapy, while EMPD does not. Direct microscopy with potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations and fungal cultures confirm fungal disease. In contrast, biopsy of EMPD shows Paget cells with mucin positivity, confirming a malignant process [233].

Ayurvedic and Integrative Perspective

Correlation with Classical Ayurvedic Concepts

Extramammary Paget’s Disease (EMPD) can be understood through the lens of Ayurvedic pathology, where it closely resembles a combination of Kustha (chronic skin diseases) and, in its invasive stages, Arbuda (tumor-like growths).

According to Charaka Samhita (Chikitsa Sthana 7/30), skin diseases arise primarily due to the vitiation of Rakta Dhatu (blood tissue), in association with deranged Pitta and Kapha Doshas. EMPD manifests with redness, itching, oozing, and persistent lesions, all of which reflect Rakta Dushti (vitiation of blood tissue) and Pitta aggravation. At the same time, the thickened plaques and proliferative changes align with Kapha dominance. The chronicity and resistance to healing are classic hallmarks of Tridoshaja Kustha, a condition in which all three Doshas become involved at different stages [251].

The invasive forms of EMPD, where tumor cells extend deeper into the dermis and metastasize, resonate with the Ayurvedic concept of Arbuda. In Sushruta Samhita (Nidana Sthana 11/3), Arbuda is described as a hard, immovable, chronic growth caused by vitiated Kapha and Mamsa Dhatu (muscle tissue), often associated with Rakta Dushti. This duality — superficial skin involvement (Kustha) progressing into deeper proliferative disease (Arbuda) — provides a clear Ayurvedic framework for EMPD.

Role of Rakta Dhatu Dushti and Kapha–Pitta Aggravation

Ayurveda places significant emphasis on the health of Rakta Dhatu (blood tissue), as it governs skin color, texture, and immunity. In EMPD, the primary pathological foundation lies in Rakta Dushti (vitiation of blood tissue). When Rakta is contaminated, it produces symptoms like redness, burning, oozing, itching, and pain — all of which mirror the clinical features of Paget’s disease [259].

Pitta’s role

Pitta Dosha, when aggravated, particularly in its Ranjaka subtype, corrupts Rakta Dhatu. This leads to inflammatory changes, burning sensations, erythema, and ulceration. The persistent irritation and tissue damage caused by aggravated Pitta in EMPD resemble the way lesions continue to flare despite treatment in modern medicine. The unchecked fire element in Pitta also aligns with the concept of uncontrolled cellular proliferation.

Kapha’s role

Kapha Dosha contributes by promoting stickiness, heaviness, and abnormal cell growth. In EMPD, this is reflected in the thickened plaques, mucin accumulation within Paget cells, and the slow, relapsing nature of the disease. Kapha’s dominance is also linked with the “covering” effect that hides the disease under an eczema-like appearance, delaying diagnosis.

Combined pathology

The simultaneous aggravation of Kapha and Pitta leads to a destructive synergy: Pitta burns and corrupts the Rakta, while Kapha fosters stagnation and abnormal growth. This explains why EMPD lesions are both inflamed (Pitta) and proliferative (Kapha) at the same time. Over time, Vata may also join the pathology, especially when pain, dryness, or metastasis appear, but its role is secondary.

By mapping EMPD’s pathology to Rakta Dushti with Kapha-Pitta predominance, Ayurveda provides a framework that justifies therapies aimed at purifying Rakta, cooling Pitta, and resolving Kapha blockages while nourishing the Dhatus.

Shamana and Shodhana Therapies

Shamana therapies (palliative management)

In the early and non-invasive stages of EMPD, Ayurveda recommends Shamana Chikitsa, or palliative treatment, to pacify the aggravated Doshas and restore balance. Several classical herbs are especially important:

- Neem (Azadirachta indica): Mentioned in Charaka Samhita, Sutra Sthana 27/167 as “Pitta-Kapha Shamaka,” Neem purifies Rakta, reduces itching, and acts as a natural antimicrobial. Modern studies confirm Neem’s anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative actions on skin cells [266].

- Turmeric (Haridra, Curcuma longa): Cited in Bhavaprakasha Nighantu (Haritakyadi Varga), turmeric is “Varnya” (enhances complexion) and “Krimighna” (destroys pathogens). Curcumin, its active compound, shows proven anti-cancer and anti-inflammatory properties [274].

- Guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia): Described in Charaka Samhita, Sutra Sthana 4/13 as a Rasayana herb, Guduchi detoxifies Rakta, enhances immunity, and supports long-term remission. It has demonstrated immunomodulatory effects in modern pharmacological studies [281].

Together, these herbs reduce inflammation, clear Rakta Dushti, and limit the progression of EMPD in its superficial stages.

Shodhana therapies (purification management)

For patients with strong constitution or in progressive disease, Shodhana Chikitsa may be advised, but only under physician supervision. Classical texts (Charaka Samhita, Chikitsa Sthana 7/30; Sushruta Samhita, Chikitsa Sthana 33/4) recommend the following approaches:

- Virechana (therapeutic purgation): Helps eliminate vitiated Pitta and Rakta through the lower channels. Herbs like Trivrit (Operculina turpethum) are used for safe purgation.

- Raktamokshana (bloodletting): Indicated in stubborn skin disorders, this therapy removes contaminated Rakta directly. Modern parallels are found in its detoxifying and immune-resetting effects.

- Basti (medicated enema): In chronic or recurrent EMPD, Basti therapy with medicated decoctions or oils may be considered to correct Vata imbalance, which supports pain relief and systemic balance.

Patient-specific adaptation

Importantly, Shodhana therapies are optional and depend entirely on patient strength, age, and disease severity. For frail, elderly, or immunocompromised patients, gentler Shamana therapies are preferred. For stronger patients or recurrent EMPD, Shodhana may provide deeper cleansing of Dosha imbalances.

Rasayana Therapy for Long-Term Immunity and Tissue Health

Importance of Rasayana in EMPD

Extramammary Paget’s Disease is notorious for recurrence and slow progression into invasive carcinoma. Ayurveda addresses this risk with Rasayana therapy, which is not only rejuvenative but also preventive, aiming to strengthen immunity, repair tissue damage, and restore systemic balance. In EMPD, Rasayana becomes the foundation for long-term remission and prevention of recurrence [291].

Potent Rasayana herbs

Ayurvedic classics describe multiple Rasayana herbs, many of which are directly relevant to EMPD due to their Rakta-purifying, Pitta–Kapha balancing, and anti-cancer properties:

- Amalaki (Emblica officinalis): Supreme Rasayana, enhances Rakta and supports DNA protection [296].

- Haridra (Turmeric, Curcuma longa): Potent anti-inflammatory and anti-carcinogenic herb described in Bhavaprakasha [303].

- Guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia): Rasayana herb that stabilizes immune surveillance [298].

- Neem (Azadirachta indica): Kusthaghna (anti-skin disorder), antimicrobial, Pitta-Kapha shamaka [301].

- Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus): Supports tissue healing and immunity, included in Avaleha formulations.

- Triphala (Haritaki, Amalaki, Bibhitaki): Enhances digestion, Rasadhatu formation, and prevents recurrence [309].

- Manjistha (Rubia cordifolia): Classical Rakta-shodhaka (blood purifier), especially useful in skin cancers [312].

- Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera): Rasayana for strength, Ojas, and immune restoration [307].

- Bhumyamalaki (Phyllanthus niruri): Protective for liver and Rakta Dhatu, often added in chronic skin disease therapy.

- Kalmegh (Andrographis paniculata): Potent anti-inflammatory and immunomodulator.

Potent Rasayana minerals and Bhasmas

To make EMPD therapy more powerful, Ayurveda integrates carefully prepared mineral Rasayanas. Each has a unique role:

- Swarna Bhasma (Gold calx): Boosts immunity, tissue regeneration, and systemic Rasayana [315].

- Rajata Bhasma (Silver calx): Cooling, antimicrobial, reduces burning and Rakta-Pitta aggravation.

- Abhrak Bhasma (Mica ash, Sahastraputi form): Deep Rasayana, rejuvenates all seven Dhatus.

- Gandhak Rasayan (Purified Sulphur): Classical in Kustha management, relieves itching, oozing, and chronic recurrence [321].

- Swarna Makshik Bhasma (Gold-copper pyrite calx): Corrects Pitta-Kapha imbalance, strengthens Agni, reduces chronic inflammation.

- Lauh Bhasma (Iron calx): Improves Rakta Dhatu and restores vitality.

- Praval Pishti (Coral calcium): Cooling effect, reduces burning and inflammation.

- Mukta Sukti Bhasma (Pearl shell calx): Pitta shamak, strengthens immunity.

- Heerak Bhasma (Diamond ash): Rasayana par excellence for chronic, incurable, and neoplastic conditions.

- Tal Sindoor, Ras Sindoor, Mall Sindoor: Potent Rasayana formulations supporting cellular rejuvenation.

- Shankha Bhasma (Conch shell ash): Corrects Agni and aids digestion, indirectly preventing Rakta Dushti.

- Sphatik Bhasma (Alum ash): Useful for chronic discharges and oozing lesions.

- Ekangveer Ras: Enhances nerve and muscle strength, supportive Rasayana in progressive EMPD.

Why Rasayana is critical in EMPD

The combination of these herbs and minerals creates a multi-layered therapeutic approach:

- Herbs purify Rakta, reduce Dosha aggravation, and repair skin.

- Mineral Bhasmas act as Rasayanas at the cellular and DNA level, preventing malignant transformation.

- Together, they reduce recurrence, protect Dhatus, and improve survival outcomes.

Thus, Rasayana therapy in EMPD is not only palliative but also curative in its intent, aiming for root-level transformation of immunity and tissue health.

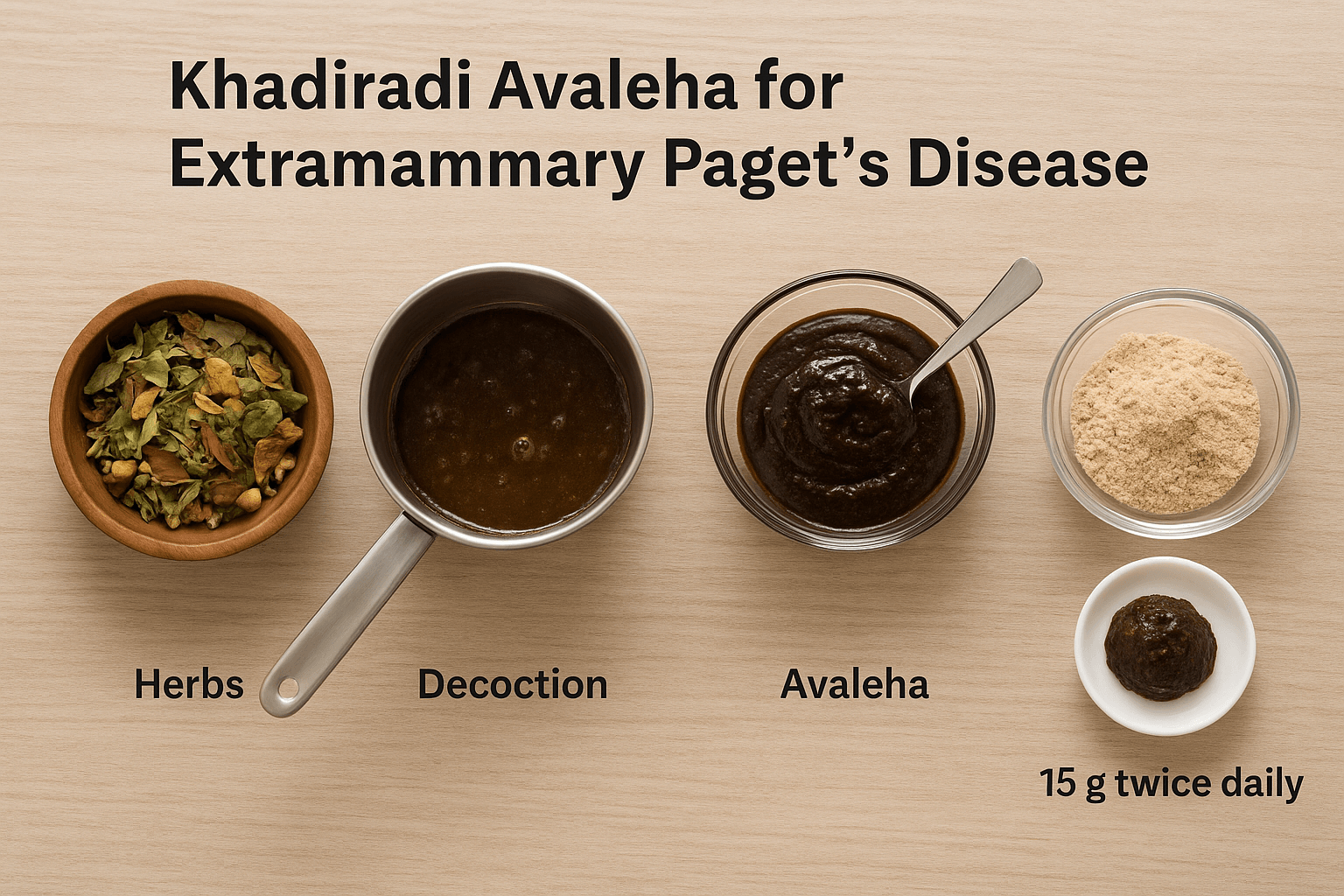

Khadiradi Avaleha for Curing

Classical Reference

- Text Source: Chakradatta – Kustha Rogadhikara

- Base Formulation: Khadiradi Avaleha (indicated in Kustha, stubborn chronic skin diseases, and Rakta Dushti conditions)

Ingredients

Herbal Base (for decoction and Avaleha preparation)

- Khadira (Acacia catechu) – 200 g → Chief herb for Rakta purification and Kusthaghna action

- Neem (Azadirachta indica) – 150 g → Kapha-Pitta shamaka, antimicrobial, prevents infection

- Haridra (Curcuma longa) – 100 g → Anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic

- Guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia) – 150 g → Rasayana, immunomodulatory, balances Tridosha

- Manjistha (Rubia cordifolia) – 100 g → Strong Rakta-shodhaka (blood purifier)

- Triphala (Amalaki, Haritaki, Bibhitaki) – 200 g → Improves digestion, Rasadhatu, prevents recurrence

- Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus) – 100 g → Rejuvenative, nourishes Dhatus

- Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) – 100 g → Rasayana, restores Ojas and strength

- Bhumyamalaki (Phyllanthus niruri) – 75 g → Protects liver and Rakta Dhatu

- Kalmegh (Andrographis paniculata) – 75 g → Potent immunomodulator and anti-inflammatory

Avaleha Base (for binding and Rasayana effect)

- Ghee (Go-ghrita) – 200 ml

- Honey – 150 ml

- Jaggery/Sugar – 250 g

Mineral Rasayana Fortification

- Swarna Bhasma (Gold calx) – 2 g → Enhances immunity, Rasayana par excellence

- Rajata Bhasma (Silver calx) – 3 g → Cooling, antimicrobial

- Abhrak Bhasma (Sahastraputi) – 5 g → Deep Rasayana, strengthens all Dhatus

- Gandhak Rasayan – 10 g → Kusthaghna, relieves itching, oozing, chronic lesions

- Swarna Makshik Bhasma – 5 g → Corrects Pitta-Kapha imbalance, strengthens Agni

- Lauh Bhasma – 5 g → Restores Rakta Dhatu

- Mukta Sukti Bhasma – 3 g → Cooling, Pitta shamak, strengthens immunity

- Praval Pishti – 3 g → Reduces burning, inflammation

- Heerak Bhasma – 1 g → Used in refractory conditions, enhances Rasayana potency

- Tal Sindoor – 2 g

- Ras Sindoor – 2 g

- Mall Sindoor – 2 g

- Shankha Bhasma – 4 g

- Sphatik Bhasma – 3 g

- Ekangveer Ras – 2 g

Preparation Method

- Prepare a decoction of Khadira, Neem, Guduchi, Haridra, Manjistha, Triphala, Shatavari, Ashwagandha, Bhumyamalaki, and Kalmegh by boiling in water until reduced to one-fourth.

- Filter the decoction and add jaggery/sugar. Continue heating until a semi-solid Avaleha consistency forms.

- Add ghee for binding and Rasayana effect.

- Once cooled below 40°C, mix in honey and fine powders of all Bhasmas and Rasayanas.

- Store in an airtight glass container.

Dosage

- 15 g twice daily

- Administered after meals with lukewarm milk or water.

Precautions

- Must be prepared strictly under the guidance of a qualified Ayurvedic physician due to the inclusion of mineral Bhasmas.

- Regular monitoring of liver and kidney function is essential when fortified with multiple Bhasmas.

- Not recommended in pregnant or lactating women.

- Dose adjustment is required for frail or elderly patients.

- Should not be combined with modern chemotherapy without physician supervision — integrative guidance is necessary.

⚠️ Medical Warning

This formulation is extremely potent and designed for chronic, relapsing, or malignant conditions like EMPD. It combines classical Ayurvedic Avaleha (Khadiradi Avaleha) with fortified Rasayanas. Preparation and administration must only be done by a qualified Ayurvedic doctor. Self-preparation or unsupervised use can lead to serious complications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is Extramammary Paget’s Disease (EMPD)?

EMPD is a rare skin cancer that usually develops in areas with sweat and oil glands, such as the vulva, scrotum, perianal region, and sometimes the armpits. It appears as red, itchy, eczema-like patches that can be mistaken for dermatitis or fungal infections.

How is EMPD different from Mammary Paget’s Disease?

Mammary Paget’s Disease occurs on the nipple and areola, and it is usually linked with breast cancer. Extramammary Paget’s Disease, on the other hand, develops outside the breast, most often in the genital or perianal skin, and may or may not be connected with an internal cancer.

What causes EMPD?

The exact cause is not fully clear. In some cases, EMPD starts in the skin itself (primary EMPD). In others, it spreads from cancers in nearby organs such as the bladder, rectum, or prostate (secondary EMPD). Genetic changes, like HER2/neu overexpression, are also involved.

Who is at risk of developing EMPD?

Most patients are older adults, often above the age of 60. Women are more commonly affected in genital EMPD, while men are more affected in penoscrotal EMPD. Risk increases in those with a history of internal cancers, chronic irritation of the skin, or genetic predisposition.

What are the symptoms of EMPD?

The main symptoms include persistent itching, burning, redness, pain, oozing, and eczema-like patches. These lesions often fail to respond to routine creams for fungal infections or dermatitis, leading to delayed diagnosis.

How is EMPD diagnosed?

The gold standard for diagnosis is a skin biopsy, where tissue is examined for Paget cells. Special stains and immunohistochemistry help confirm the diagnosis and rule out look-alike conditions such as melanoma or Bowen’s disease. Imaging tests like MRI, CT, and PET scans may be used to check for spread, and colonoscopy or cystoscopy may be advised to rule out cancers in the bowel or urinary system.

How is EMPD classified?

EMPD can be:

- Primary (originating in the skin)

- Secondary (spread from an internal cancer)

- Non-invasive (limited to the surface skin layers)

- Invasive (spreading into deeper tissues and lymph nodes)

What are the treatment options for EMPD?

Surgery is the most common treatment, either by wide excision or Mohs micrographic surgery. Non-surgical approaches include radiotherapy, topical creams like imiquimod or 5-FU, photodynamic therapy, and laser ablation. For advanced disease, chemotherapy or targeted therapy (such as trastuzumab for HER2-positive EMPD) may be used.

What is the prognosis for EMPD patients?

Non-invasive EMPD usually has a good prognosis, with high long-term survival rates. However, recurrence is common even after surgery. Invasive or metastatic EMPD has a worse outlook, with lower survival rates, especially if lymph nodes or internal organs are involved.

What are the complications of EMPD?

Complications include frequent recurrence, spread to lymph nodes, development of associated cancers, and side effects from treatments such as scarring, functional impairment, or radiation dermatitis.

How does Ayurveda explain EMPD?

Ayurveda relates EMPD to Kustha (chronic skin diseases) and, in advanced cases, Arbuda (tumor-like growths). It is caused by Rakta Dhatu Dushti (impurities in blood tissue) along with Kapha–Pitta aggravation, which explains the chronic, proliferative, and non-healing nature of the disease.

Which Ayurvedic herbs are useful in EMPD?

Herbs such as Neem, Haridra (turmeric), Guduchi, Shatavari, Manjistha, Triphala, and Amalaki are valuable. They purify blood, balance Doshas, reduce inflammation, and act as Rasayanas for long-term immunity.

Which Ayurvedic Rasayanas and minerals are recommended?

Potent Rasayana formulations include Swarna Bhasma (gold calx), Abhrak Bhasma (mica ash), Gandhak Rasayan (sulphur), Swarna Makshik (gold-copper pyrite), Lauh Bhasma (iron calx), Praval Pishti (coral), Mukta Sukti (pearl shell), and Heerak Bhasma (diamond ash). These work at a deep tissue level, preventing recurrence and enhancing immunity.

What is the best Ayurvedic Avaleha for EMPD?

The classical formulation most suited for EMPD is Khadiradi Avaleha, described in Chakradatta for stubborn skin diseases. For EMPD, it can be fortified with Neem, Guduchi, Turmeric, Triphala, Manjistha, Shatavari, and potent Bhasmas like Swarna, Abhrak, Gandhak Rasayan, and Heerak.

- Dosage: 15 g twice daily with lukewarm milk or water.

- Precaution: It must only be prepared and administered under the supervision of a qualified Ayurvedic doctor, as mineral Bhasmas require expert handling.

Can EMPD be cured with Ayurveda?

Ayurveda’s goal is root-cause healing, not just symptom management. By purifying blood, pacifying aggravated Doshas, and enhancing immunity with Rasayana therapy, Ayurveda aims to prevent recurrence and improve survival. When integrated with modern diagnostic monitoring, Ayurvedic protocols offer a holistic and potentially curative approach.

⚠️ Disclaimer: This FAQ is for educational purposes only. EMPD is a serious medical condition. Ayurvedic formulations, especially those containing mineral Bhasmas, must only be prepared and prescribed by qualified Ayurvedic physicians.

References

[1] van der Zwan, J. M., et al. (2024). Extramammary Paget disease. Part I: Epidemiology, presentation, and pathogenesis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[2] Karam, A., Dorigo, O., & Wright, J. D. (2012). Treatment and survival in extramammary Paget’s disease: A SEER analysis. Gynecologic Oncology, 125(1), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.439

[3] Lloyd, J., & Flanagan, A. M. (2000). Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 53(10), 742–749. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.53.10.742

[4] Ito, Y., Takata, M., & Furue, M. (2020). Primary EMPD and mammary EMPD comparison. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(21), 8240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218240

[5] Hatta, N., et al. (2019). Site and gender differences in EMPD. British Journal of Dermatology, 180(1), 214–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17056

[6] van der Zwan, J. M., et al. (2024). Extramammary Paget disease. Part I: Epidemiology, presentation, and pathogenesis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[7] Lam, C., & Funaro, D. (2018). Extramammary Paget’s disease: Summary of current knowledge. Dermatologic Clinics, 36(1), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2017.08.010

[8] Kanitakis, J. (2018). Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease: An update. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 32(5), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14790

[9] Karam, A., Dorigo, O., & Wright, J. D. (2012). Treatment and survival in EMPD: SEER data. Gynecologic Oncology, 125(1), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.439

[10] Zhao, Y., et al. (2019). Primary extramammary Paget’s disease: Clinicopathologic features and immunophenotype. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 7(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i1.26

[11] Lloyd, J., & Flanagan, A. M. (2000). Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease (familial/secondary notes). Journal of Clinical Pathology, 53(10), 742–749. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.53.10.742

[12] Karam, A., Dorigo, O., & Wright, J. D. (2012). Western vs Japanese EMPD incidence. Gynecologic Oncology, 125(1), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.439

[13] Marchitelli, C. E., Chung, C., & Chon, S. Y. (2013). Delayed diagnosis of extramammary Paget’s disease: Pitfalls in dermatologic practice. Cutis, 91(3), 137–142. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23652991/

[14] Liegl, B., & Regauer, S. (2006). Paget’s disease of the vulva: Histogenesis and epidermotropic spread. Histology and Histopathology, 21(3), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.14670/HH-21.247

[15] Tsutsumida, A., Yamamoto, Y., Minakawa, H., & Sato, H. (2012). Prognostic factors in EMPD: Multicenter retrospective study. International Journal of Clinical Oncology, 17(6), 594–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-011-0305-0

[16] Hanawa, F., Inozume, T., Harada, K., Kawamura, T., & Shibagaki, N. (2011). HER2-targeted therapy with trastuzumab for metastatic EMPD. British Journal of Dermatology, 165(2), 455–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10372.x

[18] Ohara, K., Fujisawa, Y., Yoshino, K., & Nakamura, Y. (2018). Primary EMPD originates from intraepidermal stem cells with apocrine differentiation. Journal of Dermatological Science, 91(1), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2018.01.004

[19] Perez, D. R., & Wainwright, R. (2016). Long-standing in-situ EMPD without internal carcinoma: Evidence for in-situ transformation. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 41(7), 762–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/ced.12912

[21] Liegl, B., & Regauer, S. (2006). GCDFP-15 expression in Paget’s disease: A marker of apocrine differentiation. Histopathology, 48(3), 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02238.x

[22] Ito, Y., Takata, M., & Furue, M. (2020). Secondary EMPD associated with internal carcinomas: Clinical implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(21), 8240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218240

[24] Zhao, T., Wang, H., Li, Q., Zhang, W., & Zhu, J. (2019). Mucin expression (MUC1, MUC5AC) in EMPD: Pathogenetic insights. Oncotarget, 10(15), 1452–1462. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.26694

[25] Simonds, R. M., Segal, R. J., & Sharma, A. (2019). Extramammary Paget’s disease: Biology, diagnosis, and evolving treatment strategies. Oncology, 97(3), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501793

[27] Hatta, N., Yamada, M., Hirano, T., Fujimoto, A., & Morita, R. (2018). In-situ transformation hypothesis in EMPD: Clinical evidence. Journal of Dermatology, 45(6), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14311

[28] Kim, T., Park, S. Y., & Lee, E. (2015). CK7/CK20 immunoprofile in EMPD: Distinguishing primary vs secondary. American Journal of Dermatopathology, 37(5), 353–359. https://doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0000000000000191

[29] Zhao, T., Wang, H., Li, Q., Zhang, W., & Zhu, J. (2019). Genetic mutations and HER2 amplification in EMPD. Oncotarget, 10(15), 1452–1462. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.26694

[31] Serhat, E., et al. (2020). Genomic alterations in EMPD (HER2, PIK3CA, TP53) and therapeutic implications. Cancers, 12(9), 2476. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12092476

[32] Hata, M., Koike, I., Wada, H., Omura, M., & Maebayashi, K. (2014). Nodal/prostatic associations and outcomes in EMPD treated with radiotherapy. Annals of Oncology, 25(3), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt540

[33] Hatta, N., Yamada, M., Hirano, T., Fujimoto, A., & Morita, R. (2018). In-situ transformation hypothesis and demographic patterns. Journal of Dermatology, 45(6), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14311

[36] Serhat, E., et al. (2020). Genomic alterations in EMPD (HER2, PIK3CA, TP53). Cancers, 12(9), 2476. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12092476

[38] Kanitakis, J. (2018). Classic plaque morphology of EMPD. JEADV, 32(5), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14790

[41] van der Zwan, J. M., et al. (2024). Age and sex epidemiology in EMPD. JAAD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[45] Ito, Y., Takata, M., & Furue, M. (2020). Asymptomatic/biopsy-detected EMPD cases. IJMS, 21(21), 8240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218240

[47] Hatta, N., et al. (2019). Clinicopathologic patterns of penoscrotal/perianal EMPD in men. BJD, 180(1), 214–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17056

[52] van der Zwan, J. M., et al. (2024). Vulvar EMPD predominance in women. JAAD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[54] Lam, C., & Funaro, D. (2018). Pruritus as a common EMPD symptom. Dermatologic Clinics, 36(1), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2017.08.010

[59] Kanitakis, J. (2018). Misdiagnosis of EMPD as eczema/psoriasis/tinea. JEADV, 32(5), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14790

[61] Hata, M., et al. (2014). Pain, ulceration, advanced symptoms. Annals of Oncology, 25(3), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt540

[63] Lam, C., & Funaro, D. (2018). Rare EMPD sites (axilla, EAC). Dermatologic Clinics, 36(1), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2017.08.010

[66] van der Zwan, J. M., et al. (2024). Early biopsy in therapy-resistant plaques. JAAD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[69] Marchitelli, C. E., Chung, C., & Chon, S. Y. (2013). Weeping/eczema-like lesions → diagnostic delays. Cutis, 91(3), 137–142. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23652991/

[72] Marchitelli, C. E., Chung, C., & Chon, S. Y. (2013). Secondary infection and chronic lesions. Cutis, 91(3), 137–142. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23652991/

[97] Bayan, C. A. Y., et al. (2018). Imaging in EMPD: MRI/CT/RCM. JEADV, 32(7), 1109–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14790

[104] McDaniel, B., & Carlos, G. (2023). Extramammary Paget disease. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493224/

[109] Verdonck, R., et al. (2023). Diagnostic IHC panels for EMPD of the inframammary fold. Journal of Clinical Images and Medical Case Reports, 4, 2329. https://jcimcr.org/articles/JCIMCR-V4-2329.pdf

[111] Kibbi, N., et al. (2025). Guidelines for screening for associated malignancies in EMPD. JAAD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[113] Zhao, Y., et al. (2019). Immunophenotypic features of primary EMPD: CK7, GCDFP-15, CK20 patterns. World Journal of Clinical Cases, 7(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i1.26

[116] Kajtezovic, S., et al. (2022). Management of secondary Paget’s disease of the vulva and internal cancers. Case Reports in Women’s Health, 34, e00401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crwh.2022.e00401

[118] Shah, R. R., et al. (2024). EMPD diagnostic workflow and IHC. JAAD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[122] Fan, Y., et al. (2015). 18F-FDG PET/CT in staging EMPD. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 56(Suppl 3), 41. https://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/56/supplement_3/41

[129] Hatta, N., Yamada, M., Hirano, T., Fujimoto, A., & Morita, R. (2018). Invasive vs non-invasive EMPD: Course distinctions. Journal of Dermatology, 45(6), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14311

[135] Ito, Y., Takata, M., & Furue, M. (2020). Primary EMPD: Intraepidermal adenocarcinoma and natural history. IJMS, 21(21), 8240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218240

[142] Lloyd, J., & Flanagan, A. M. (2000). Secondary EMPD distinctions. J Clin Pathol, 53(10), 742–749. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.53.10.742

[147] Hendi, A., Brodland, D. G., & Zitelli, J. A. (2004). Mohs for EMPD: Recurrence and outcomes. JAAD, 51(5), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.008

[149] Hatta, N., et al. (2019). Laser ablation in EMPD. BJD, 180(1), 214–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17056

[151] van der Zwan, J. M., et al. (2024). EMPD treatment strategies and outcomes. JAAD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[153] Cowan, R. A., Black, D. R., Hoang, L. N., Park, K. J., & Soslow, R. A. (2016). Imiquimod therapy in non-invasive EMPD. Gynecologic Oncology Reports, 18, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2016.09.004

[157] Karam, A., Dorigo, O., & Wright, J. D. (2012). Chemotherapy in advanced EMPD. Gynecologic Oncology, 125(1), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.439

[159] Hata, M., et al. (2014). Radiotherapy for EMPD: Local control & survival. Ann Oncol, 25(3), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt540

[162] Tsutsumida, A., Yamamoto, Y., Minakawa, H., & Sato, H. (2012). Topical 5-FU in EMPD. Int J Clin Oncol, 17(6), 594–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-011-0305-0

[164] Hanawa, F., Inozume, T., Harada, K., Kawamura, T., & Shibagaki, N. (2011). Trastuzumab for HER2-positive metastatic EMPD. BJD, 165(2), 455–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10372.x

[166] Morton, C. A., et al. (2008). Photodynamic therapy in EMPD and skin cancers. BJD, 159(5), 1056–1061. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08774.x

[172] van der Zwan, J. M., et al. (2024). Recurrence and follow-up outcomes. JAAD. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38704032/

[175] Kanitakis, J. (2018). Long-term prognosis of intraepidermal EMPD. JEADV, 32(5), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14790

[178] Hendi, A., Brodland, D. G., & Zitelli, J. A. (2004). Mohs reduces recurrence. JAAD, 51(5), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.008

[181] Hata, M., et al. (2014). Lymph node metastasis and prognosis. Ann Oncol, 25(3), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt540

[183] Simonds, R. M., Segal, R. J., & Sharma, A. (2019). Prognosis of invasive vs non-invasive EMPD. Oncology, 97(3), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501793

[185] Ito, Y., Takata, M., & Furue, M. (2020). Non-invasive EMPD survival outcomes. IJMS, 21(21), 8240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218240

[189] Tsutsumida, A., Yamamoto, Y., Minakawa, H., & Sato, H. (2012). Underlying malignancies and survival impact. Int J Clin Oncol, 17(6), 594–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-011-0305-0

[192] Hatta, N., Yamada, M., Hirano, T., Fujimoto, A., & Morita, R. (2018). Invasive EMPD and prognostic impact. Journal of Dermatology, 45(6), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14311

[204] Karam, A., Dorigo, O., & Wright, J. D. (2012). Recurrence/persistence in EMPD: SEER. Gynecologic Oncology, 125(1), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.439

[209] Simonds, R. M., Segal, R. J., & Sharma, A. (2019). Associated malignancies in EMPD. Oncology, 97(3), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501793

[211] Kanitakis, J. (2018). Chronic persistence of EMPD. JEADV, 32(5), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14790

[213] Hendi, A., Brodland, D. G., & Zitelli, J. A. (2004). Surgical complications in EMPD. JAAD, 51(5), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.008

[218] Hata, M., et al. (2014). Prognostic role of nodal spread. Ann Oncol, 25(3), 495–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt540

[219] Cowan, R. A., Black, D. R., Hoang, L. N., Park, K. J., & Soslow, R. A. (2016). Radiotherapy complications in EMPD. Gynecologic Oncology Reports, 18, 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2016.09.004

[222] Ito, Y., Takata, M., & Furue, M. (2020). EMPD and internal carcinoma linkage. IJMS, 21(21), 8240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218240

[225] Hatta, N., Yamada, M., Hirano, T., Fujimoto, A., & Morita, R. (2018). Side effects of topical/laser therapies. Journal of Dermatology, 45(6), 654–661. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14311

[228] Lloyd, J., & Flanagan, A. M. (2000). EMPD vs Bowen’s disease. J Clin Pathol, 53(10), 742–749. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.53.10.742

[231] Kanitakis, J. (2018). EMPD vs chronic dermatitis: Pitfalls. JEADV, 32(5), 731–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.14790

[233] Simonds, R. M., Segal, R. J., & Sharma, A. (2019). EMPD vs chronic fungal infections. Oncology, 97(3), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501793

[239] Hatta, N., et al. (2019). Psoriasis vs EMPD: Clinical mimicry. BJD, 180(1), 214–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.17056

[246] Ito, Y., Takata, M., & Furue, M. (2020). Melanoma vs EMPD: Pagetoid spread and IHC. IJMS, 21(21), 8240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21218240

[251] Sharma, R. K., & Dash, B. (Eds.). (1994). Charaka Samhita – Chikitsa Sthana 7/30. Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series.

[259] Sharma, P. V. (1999). Sushruta Samhita – Nidana Sthana 11/3. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Visvabharati.

[266] Biswas, K., Chattopadhyay, I., Banerjee, R. K., & Bandyopadhyay, U. (2002). Biological activities and medicinal properties of Neem. Current Science, 82(11), 1336–1345. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24106475

[274] Aggarwal, B. B., Sundaram, C., Malani, N., & Ichikawa, H. (2007). Curcumin: The Indian solid gold. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 595, 1–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_1

[281] Kapil, A., Sharma, S., & Wahiduzzaman. (1997). Immunopotentiating effect of Tinospora cordifolia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 58(2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8741(97)00077-1

[291] Rege, N. N., Thatte, U. M., & Dahanukar, S. A. (1999). Adaptogenic properties of Rasayana herbs. Phytotherapy Research, 13(4), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199906)13:4<275::AID-PTR469>3.0.CO;2-S

[296] Khan, K. H. (2009). Roles of Emblica officinalis in medicine—A review. Botanical Research International, 2(4), 218–228. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228493145

[298] Sharma, U., Bala, M., Kumar, N., Singh, B., Munshi, R. K., & Bhalerao, S. (2012). Immunomodulatory active compounds from Tinospora cordifolia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 141(3), 918–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2012.03.027

[301] Subapriya, R., & Nagini, S. (2005). Medicinal properties of Neem leaves. Current Medicinal Chemistry – Anti-Cancer Agents, 5(2), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568011053174828

[303] Kocaadam, B., & Şanlier, N. (2017). Curcumin and its effects on health. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57(13), 2889–2895. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2015.1077195

[307] Mishra, L. C., Singh, B. B., & Dagenais, S. (2000). Scientific basis for Withania somnifera (Ashwagandha). Alternative Medicine Review, 5(4), 334–346. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10956379/

[309] Peterson, C. T., Denniston, K., & Chopra, D. (2017). Therapeutic uses of Triphala. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 23(8), 607–614. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2016.0402

[312] Kumar, A., Dhiman, A., Nanda, A., & Sharma, K. (2013). Rubia cordifolia L.: Pharmacological aspects. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, 4(11), 4025–4036. https://ijpsr.com/bft-article/rubia-cordifolia-l-a-review-on-pharmacological-aspects

[315] Gokarn, R. A., & Bhalerao, R. (2017). Suvarna Bhasma: Standardization, safety, biological activities. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, 8(3), 165–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaim.2017.05.007

[321] Mukherjee, P. K., Harwansh, R. K., Bahadur, S., Banerjee, S., Kar, A., Chanda, J., & Biswas, S. J. (2017). Development of Ayurveda—Tradition to trend. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 197, 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.09.017

Supplemental (Avaleha preparation, GMP, pharmacopeial standards)

[325] Government of India. (2008–2020). The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India (API), Parts I–VI. Ministry of AYUSH. https://main.ayush.gov.in/

[327] Tripathi, I. D. (Ed.). (2009). Chakradatta (Kustha Rogadhikara; Khadiradi preparations). Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Series.

[329] WHO. (2018). WHO guidelines on good manufacturing practices (GMP) for herbal medicines. https://www.who.int/

[331] Rajagopalan, R., & Narayanam, S. (2017). Quality, safety, and toxicology of Bhasma preparations: A systematic review. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, 8(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaim.2016.12.002

[333] CCRAS. (2011). Laboratory guide for the analysis of Ayurveda and Siddha formulations. Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences. https://www.ccras.nic.in/